中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 陈锡玮, 许蒙, 冯程, 胡昌华

- Chen Xiwei, Xu Meng, Feng Cheng, Hu Changhua

- 真菌聚酮化合物生物合成研究进展

- Progress in fungal polyketide biosynthesis

- 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(2): 151-164

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2018, 34(2): 151-164

- 10.13345/j.cjb.170219

-

文章历史

- Received: May 31, 2017

- Accepted: July 24, 2017

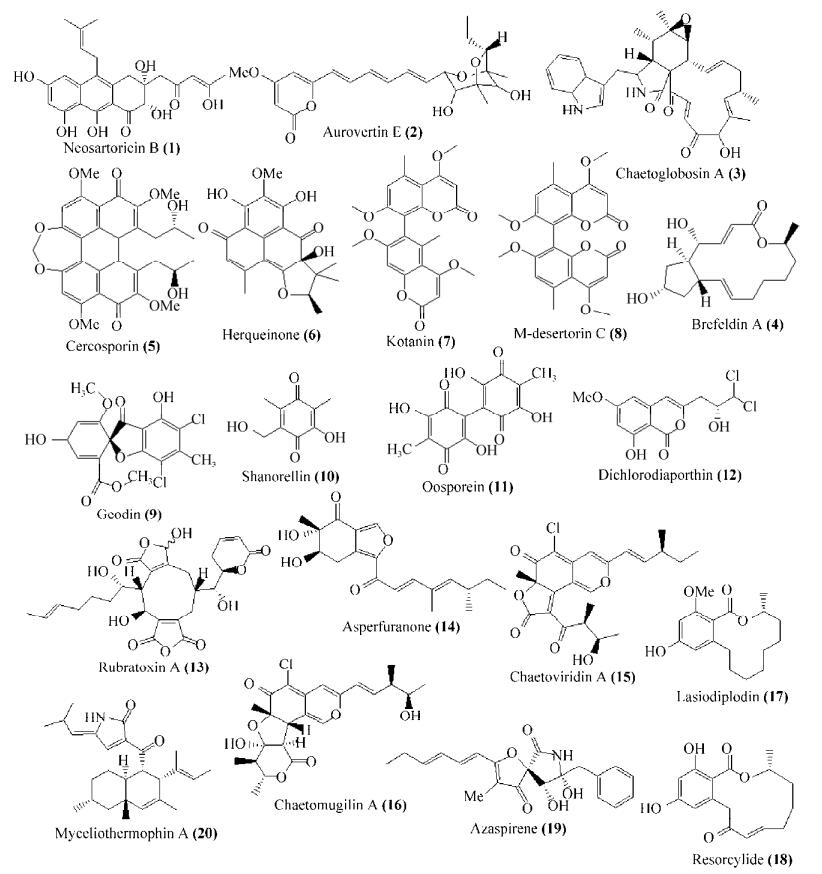

天然产物是自然界(真菌、细菌、植物以及动物等)中分离得到的化合物,其在药物开发及发展中起着重要作用[1]。真菌天然产物是生物活性药物的主要来源之一,如天然抗生素青霉素(Penicillin)、抗真菌药灰黄霉素(Griseofulvin)、降血脂药洛伐他丁(Lovastatin)。真菌天然产物根据生物合成来源主要分为4类,即聚酮类(Polyketides,PKs)、非核糖体多肽类(Non-ribosomal peptides,NRPs)、萜类(Terpenoids)和生物碱类(Alkaloids)。根据每个延伸单元还原程度的不同,真菌聚酮合酶分为非还原(NR)、部分还原(PR)和高度还原(HR) PKSs[2]。此外,由于生物合成基因簇(Gene cluster)包含多个催化酶,故聚酮化合物有时由杂合型HR-NR PKSs和PKS-NRPSs催化而成。NR-PKSs催化合成芳环产物如黄曲霉毒素(Aflatoxins),其是由真菌黄曲霉Aspergillus flavus和寄生曲霉Aspergillus parasiticus产生的二聚香豆素衍生物(AFB1、AEB2、AFG1、AFG2),具有高度的肝毒性、肝致癌性、致畸性和诱变性[3]。Aflatoxins的生物合成基因簇大小约为70 kb,包括20个开放阅读框(ORF),其生物合成至少需要18个酶参与催化作用[4]。PR-PKSs催化聚-β-酮酯酰链的酮基团特异性还原如6-甲基水杨酸,HR-PKSs催化合成高度还原的聚酮化合物如Neosartoricin B (1)[5]。不同类型和数量的亚基缩合和进一步修饰形成了具有广泛生物活性的真菌聚酮化合物(图 1),如Aurovertin E (2)能有效地抑制三磷酸合酶的活性[6],Chaetoglobosin A (3)有哺乳动物肌动蛋白抑制活性[7],Brefeldin A (4)具有抗真菌、抗细菌和抗肿瘤活性[8]。真菌聚酮化合物除了广泛生物活性,它们的结构多样性也是重要的特征,如Cercosporin (5)含2分子萘并吡喃酮的去甲基-决明内酯和二氧杂环庚烷结构[9],Herqueinone (6)含有“非线性”环化成的三环结构[10],Kotanin (7)和M-desertorin C (8)含有苯氧基自由偶联形成的二芳基结构[11]。这些复杂的结构和广泛的生物活性吸引了科研工作者对其生物合成途径及生物合成中所涉及的生物酶催化机制研究的兴趣。基于此,本文综述了最近几年通过阐明生物合成基因或酶所报道的真菌聚酮化合物的生物合成及其机制。

|

| 图 1 近年来发现的真菌聚酮化合物的化学结构 Figure 1 Chemical structures of fungal polyketide discovered in recent years |

| |

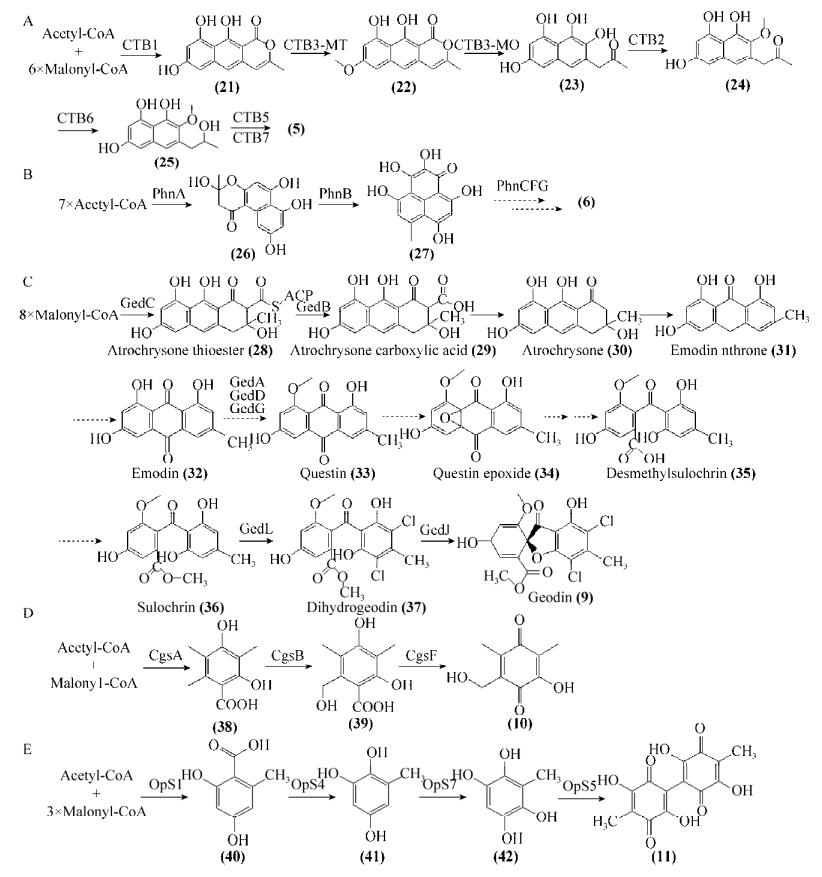

真菌非还原聚酮合酶NR-PKSs负责催化合成芳环化合物,如Geodin (9)、Shanorellin (10)、Oosporein (11)。Cercosporin (5)是从植物致病菌尾孢属类烟草尾孢菌Cercospora nicotianae中分离得到的聚酮毒素。Chung课题组首次在C. nicotianae中鉴定了5的生物合成基因簇,并通过潮霉素(Hyg)分裂标签同源重组技术的单基因敲除(CTB1-8)和反向生物合成分析,提出了5可能的生物合成途径[12-15]。此外,CTB1是一个具有新型真菌硫酯酶功能的聚酮合酶,负责催化合成5的母核结构(21)[9]。随后,Newman等通过对敲除菌株代谢物的分析提出了5新的生物合成途径(图 2A)[16]。CTB1催化1分子乙酰辅酶A和6分子丙二酰辅酶A形成nor-toralactone (21),双功能酶CTB3先催化21甲基化形成toralactone (22),接着氧化开环形成代谢物23。O-甲基转移酶(CTB2)催化中间产物23的C6位羟基甲基化形成化合物24,其C7位2-氧代丙酮被CTB6还原为naphthalene (25)。CTB5负责25和CTB7构建的二氧杂环庚烷部分的同二聚化形成5。

|

| 图 2 来源于NR-PKSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成途径 Figure 2 Proposed biosynthetic pathway of polyketide from NR-PKSs |

| |

Herqueinone (6)的中心结构phenalenone (27)由NR-PKS催化7个乙酸单元而成,其中苯环与萘环稠合[17]。Gao等在梅花状青霉Penicillium herqueiNRRL 1040基因组中鉴定了负责6生物合成的Phn基因簇,包括7个ORF,并利用同源重组技术进行基因敲除分析了PhnA和PhnB的功能,从而提出了27的生物合成路径(图 2B)[10]。NR-PKS (PhnA)催化合成庚烯酮骨架并环化为Naphthalene pyrone (26),PhnA中新颖的PT结构域催化C4-C9羟醛缩合。FAD依赖的单氧化酶(PhnB)催化26羟基化形成27。虽然阐明了生物合成27的机制,但6完整的生物合成途径并未报道。基因簇中剩下的催化酶可能参与终产物6的生物合成,包括O-MT (PhnC)催化C2位羟基甲基化,PrT (PhnF)催化C5位二甲基烯丙基化,其也可能催化C7-O异戊烯化或C6位Friedel-Craft烷基化,FMO (PhnG)进一步催化C6羟基化,但具体参与的催化作用还需要通过基因敲除和体外酶生化证明。

来源于土曲霉Aspergillus terreus的Geodin (9)的生物合成基因簇包括13个开放阅读框。Nielsen等在构巢曲霉Aspergillus nidulans中异源表达了基因簇中9个基因,从而得到化合物9,并阐明了3个酶NR-PKS (GedC)、TF (GedR)、卤化酶(GedL)的功能(图 2C)[18]。GedC催化丙二酰辅酶A合成Atrochrysone thioester (28),在GedB作用下转化为Atrochrysone carboxylic acid (29),GedL将Sulochrin (36)转化为Dihydrogeodin (37),GedJ使其卤化为9。虽然作者提出了9的可能的生物合成途径,但是其中O-甲基转移酶(GedADG)、氧化酶(GedHK)所参与的具体催化步骤未见报道。

Chooi等在皮肤癣菌基因组中发现了1个与烟曲霉Aspergillus fumigatus[19]和费希新萨托菌Neosartorya fischeri[20]中催化合成免疫抑制剂聚酮化合物Neosartoricin基因簇同源的基因簇,该簇包含4个生物酶:聚酮合酶(NR-PKS)、β-内酰胺硫酯酶(TE)、黄素依赖的单氧化酶(FMO)、多环异戊烯基转移酶(pcPT)[5]。随后这个高度保守的核心PKS区域(NR-PKS、TE、FMO、pcPT)导入A. nidulans中获得了一个具有免疫抑制剂活性的三环聚酮类化合物Neosartoricin B (1)[5]。Neosartoricin B可能是致病真菌中沉默次级代谢产物的代表物质,其生物合成可能与neosartoricin一致,但目前详细的生物合成未通过试验证明。

基因簇内或附近的转录因子可以控制各自次级代谢产物的生物合成,但这类基因通常表达水平较低,无法检测到相应的天然产物。过表达球毛壳菌Chaetomium globosum中可能的聚酮生物合成基因簇中一个转录调控因子CgsG,激活了一个沉默基因簇并获得了天然产物Shanorellin (10)及其前体[21]。Sato等利用同源重组技术进行了基因CgsABCEF的敲除和体外生物化学分析,首次确定了10的生物合成基因簇和途径(图 2D)[22]。细胞色素P450 (CgsB)负责催化NR-PKS (CgsA)催化合成的芳族产物(38)的C5位甲基羟基化,随后单加氧酶(CgsF)催化中间体(39)脱羧形成终产物10。

Oosporein (11)具有广泛的生物活性,如杀虫活性、抗革兰氏阳性菌活性、抗病毒活性。Oosporein存在于昆虫致病菌球孢白僵菌Beauveria bassiana、布氏白僵菌Beauveria brongniartii、内生真菌草野旋孢腔菌Cochliobolus kusanoi中[23-25]。Feng等首次报道了11在B. bassiana的生物合成基因簇,并且分析了基因(OpS1-7)的催化功能,从而提出了11的生物合成途径(图 2E)[26]。NR-PKS (OpS1)催化形成4, 6-二羟-2-甲基苯甲酸(40),其被羟基化酶(OpS4)催化形成苯三酚(41),41经双氧化酶(OpS7)催化为苯并四氢呋喃(42),随后过氧化氢酶(OpS5)催化42二聚化形成卵孢菌素11。

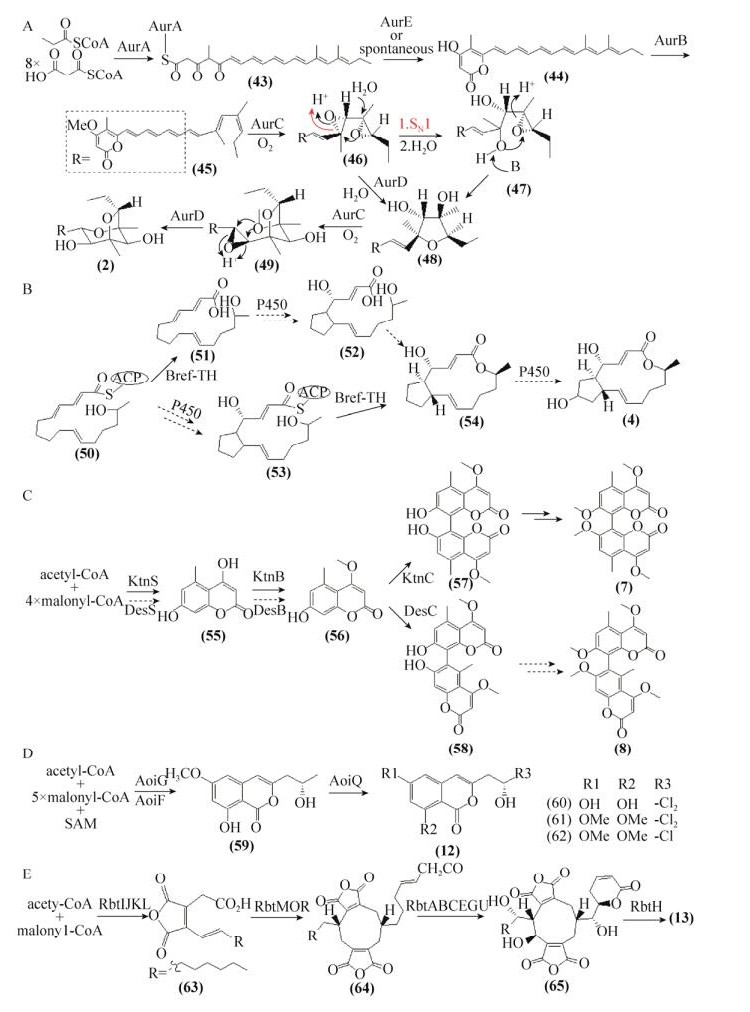

2 来源于HR-PKSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成真菌高度还原聚酮合酶(HR-PKSs)是一个多结构域酶,其催化合成结构多样的化合物,如Aurovertin E (2)、Dichlorodiaporthin (12)、Rubratoxin A (13)。在链的延伸循环中结构域的排序不同,从而导致产物的α-和β-位具有高度的灵活性,并且HR-PKSs的C-端没有硫酯酶(TE),而是依赖于游离的TE或酰基转移酶释放产物。天然产物中Aurovertins家族化合物能有效地抑制腺苷三磷酸合酶活性,其结构中含有2, 6-二氧杂[3.2.1]辛烷。Aurovertin E是家族中其他衍生物的生物合成的前体物质,其来源于齿梗孢霉Calcarisporium arbuscula中聚酮途径[6]。Yu等在C. arbuscula确定了2的生物合成基因簇,并应用重叠PCR技术[27]和潮霉素分裂标签同源重组技术[28]分别对AurA和AurBC进行敲除,根据突变株积累的中间体结构提出了2完整的生物合成途径(图 3A)[29]。Aurovertin E生物合成只需4个催化酶作用,首先HR-PKS (AurA)产生聚烯α-吡喃酮(43),然后甲基转移酶(AurB)催化吡喃酮氧甲基化形成45,黄素单氧化酶(AurC)和环氧水解酶(AurD)共同将前体的三烯末端转化为二氧杂辛烷,从而形成终产物。Citreoviridin和Asteltoxin的生物合成从多烯吡喃酮前体合成复杂的结构可能涉及相同的催化酶。

|

| 图 3 来源于HR-PKSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成途径 Figure 3 Proposed biosynthetic pathway of polyketide from HR-PKSs |

| |

蛋白转运抑制剂Brefeldin A (4)的生物合成基因簇来源于布雷正青霉Eupenicillium brefeldianum ATCC 58665,Zabala等证明了该HR-PKS (Bref-PKS)催化合成产物的还原需要NADPH,同时由硫酯水解酶(Bref-TH)控制延伸碳链的长度,并提出了4可能的生物合成途径(图 3B)[30]。途径中,HR-PKS催化合成八肽前体(50),其经过硫代水解酶释放产物51,然后经P450介导的环戊烷化形成7-脱氧BFA (52);另外,第一个成环也可以发生在硫酯酶释放和内酯化之前的ACP连接中间体,P450催化八肽前体形成53,随后在Bref-TH作用下转化为54。虽然提出了P450可能参与的催化步骤,但至今除Bref-PKS和Bref-TH外其他基因包括4个P450所参与的催化作用未被阐明,故Brefeldin A的完整生物途径并未通过实验得以验证。

天然产物中二芳基化合物普遍存在于自然界中,其通过苯氧基自由偶联形成。P-kotanin (7)的生物合成基因簇来源于黑曲霉Aspergillus niger,其中HR-PKS (KtnS)催化1分子乙酰辅酶A和4分子丙二酰辅酶A形成(55),O-甲基转移酶(KtnB)将55转化为7-demethylsiderin (56)[31-32]。Mazzaferro等通过在酿酒酵母Saccharomyces cerevisiae MH272-3fα的异源表达试验确认了来源于Aspergillus niger FGSC A1180和沙生裸胞壳Emericella desertorum的细胞色素P450 (KtnC和DesC)的催化作用(图 3C)[11]。KtnC催化2分子的56偶联形成P-kotanin的前体物质8, 8’-二聚体P-orlandin (57),其进一步O-甲基化形成P-kotanin(7)。DesC催化2分子的56偶联形成M-desertorin A (58)。虽通过同源基因功能预测了M-desertorin C基因簇中DesS和DesB分别与KtnB和KtnS同源,可能催化相同的反应,但是并未通过实验证明,包括簇中其他基因,故其完整的生物合成途径未见报道。

Diaporthin (59)来源于米曲霉Aspergillus oryzae中8号染色体上的沉默基因簇(Aoi),由PKS (AoiG)和O-MT (AoiF)共同催化合成[33]。Chankhamjon等在Aspergillus oryzae的5号染色体上发现了1个新功能催化酶AoiQ,该酶具有卤化和O-甲基的双功能催化作用,其参与所有氯化的diaporthin衍生物的生物合成(12)、(60)、(61)、(62) (图 3D)[34]。AoiQ是首个真菌脂肪族卤化酶,能催化非活性脂肪族碳原子卤化,也是首个能催化单个底物二卤化的卤化酶,从而可能促进了隐藏的天然产物的挖掘。

Nonadride类真菌天然产物具有复杂的化学结构和显著的生物活性,其代表化合物Rubratoxin A (13)为强效蛋白磷酸酶-2抑制剂[35]。Williams等提出了13生物合成中间体(64)类似物Byssochlamic acid的非核心结构来源于二聚酸酐前体[36]。Rubratoxin A在达恩吉青霉Penicillium dangeardii中的生物合成基因簇Rbt由23个ORF组成,包括HR-PKS (RbtJ)、4个双加氧酶(RbtBEGU)、1个单加氧酶(RbtA)等。随后,Bai等通过基因敲除(RbtABGH)和体外生化(RbtABEGUH)分析了基因的催化作用,由此提出了13的生物合成途径(图 3E)[37]。途径中,RbtIJKL共同催化合成63,RbtMOR催化63非对称二聚形成64,64在RbtABCEGU的作用下经多步氧化形成真菌毒素Rubrotoxin B (65),之后铁还原酶(RbtH)催化65还原为潜在抗肿瘤药物13。

3 来源于HR-NR PKSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成天然产物中含有部分还原结构的芳香化合物,如Asperfuranone (14)、Chaetoviridin A (15)、Chaetomugilin A (16),它们通常由上游HR-PKSs和下游NR-PKSs组合催化而成,其中HR-PKSs合成的还原型聚酮化合物经起始单元酰基载体蛋白(SAT)结构域转移至NR-PKSs作为起始单元做进一步延伸和环化。Somoza等在A. nidulans中重构Azaphilone中间体获得了脂氧合酶抑制剂[38]。Chiang等通过改造A. nidulans构建了新的异源表达系统,并应用该系统阐明了Aspergillus terreus中化合物14的整个生物合成(图 4A)[39]。在14的合成路径中,NR-PKS (AteafoE)、HR-PKS (AteafoG)、脂肪酶(AteafoC)催化合成66,单氧化酶(AteafoD)使其羟基化形成intermediate A (67),FAD-依赖的氧化酶(AteafoF)使其C8位羟基化形成68,经过重排脱水转化为70,其自身还原为终产物。

|

| 图 4 来源于HR-NR PKSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成途径 Figure 4 Proposed biosynthetic pathway of polyketide from HR-NR PKSs |

| |

Chaetoviridin A (15)和Chaetomugilin A (16)的生物合成基因簇Caz来源于球毛壳菌Chaetomium globosum[40]。Winter等应用融合PCR技术[41]快速构建基因CazEFM同源重组敲除片段,敲除结果显示HR-PKS (CazF)合成(4S,5R)-5-羟基-4-甲基-3-氧代己酰基三酮(73),酰基转移酶(CazE)将72转移至Cazisochromene (73)产生Chaetoviridin A (15)[40]。72可能来源于NR-PKS (CazM)和CazF共同作用催化形成的化合物Cazaldehyde A (71)。Winter等阐明了15和16生物合成途径中CazF和CazM分子间的相互作用(图 4B)[42]。CazF催化形成线性聚酮链,经SAT结构域转移至CazM进行延伸和醛醇环化,R结构域还原释放产物71。

十二环的二羟基苯甲酸内酯Lasiodiplodin (17)来源于可可毛色二孢Lasiodiplodia theobromae,此后在总状共头霉Syncephalastrum racemosum也分离得到了该化合物[43]。Lasiodiplodins生物合成来源于聚酮和中间产物9-羟基-癸酸[44]。Xu等分别在Lasiodiplodia theobromae和枝顶孢属菌Acremonium zeae中确认了17和Resorcylide (18)的生物合成基因簇,并在S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA中异源重构了17和18的生物合成(图 4C)[45]。HR-PKS (LtLasS1)和NR-PKS (LtLasS2)共同催化合成Desmethyl-lasiodiplodin-3 (74),然后O-甲基转移酶(LtLasM)催化转移为终产物;HR-PKS (AzResS1)和NR-PKS (AzResS2)共同催化合成18,不需要其他酶的修饰作用。

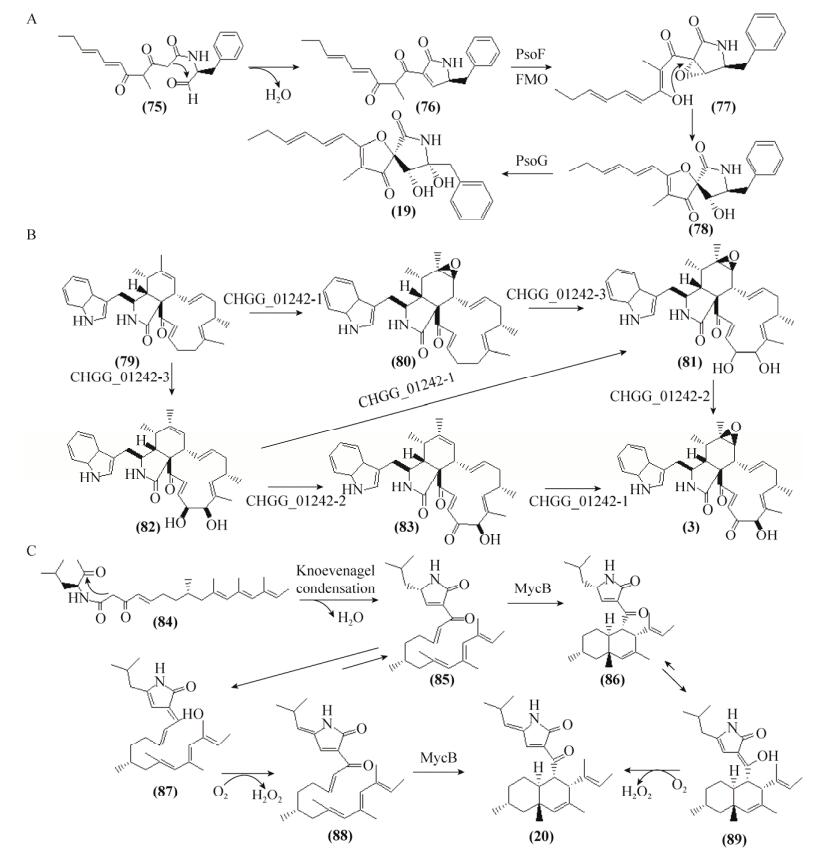

4 来源于PKS-NRPSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成真菌聚酮合酶-非核糖体肽合成酶(PKS-NRPSs)是一个约450 kDa的多功能域酶,能催化合成复杂的天然产物[46]。真菌PKS催化合成的聚酮中间产物转移至NRPS上与氨基酸进一步反应,从而合成氨基化合物。近年来,相继报道了真菌PKS-NRPS型产物的生物合成,如Pseurotin A、Azaspirene (19)、Chaetoglobosin A (4)、Myceliothermophins A (20)。Pseurotin A是Aspergillus fumigatus产生的一个免疫抑制剂,其生物合成途径中关键中间体Azaspirene来源于PKS-NRPS (PsoA)和甲基转移酶(PsoF)催化形成的中间体75[47-49]。Zou等通过在S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA共表达psoA、psoF、水解酶基因psoB以及膜依赖氧化酶基因psoG,重构了Azaspirene的生物合成(图 5A)[50]。在途径中75脱水形成76,PsoF的单氧化酶功能将其转化为77,然后经过重排形成78,PsoG催化78转化为终产物19。虽然研究表明在PKS-NRPS模块中,PKS催化合成聚酮链的α-甲基化是其转移至NRPS上进行下游修饰的先决条件和关键点,然而,甲基化步骤是否普遍作为生物化学的节点或甲基基团在天然产物中所起的作用仍然不清楚。

|

| 图 5 来源于PKS-NRPSs的聚酮化合物的生物合成途径 Figure 5 Proposed biosynthetic pathway of polyketide from PKS-NRPSs |

| |

哺乳动物肌动蛋白抑制剂Chaetoglobosin A (3)的生物合成基因簇Che来源于扩展青霉Penicillium expansum。应用RNA沉默技术鉴定了PKS-NRPS (CheA)和游离的烯酰还原酶ER (CheB)共同作用催化合成3的母核结构prochaetoglobosin I (79)[7]。Ishiuchi等通过同源重组的基因敲除和S. cerevisiae BY4741中异源表达阐明了79到3的详细生物合成途径(图 5B)[51]。PKS-NRPS和烯酰还原酶(ER)共同催化合成prochaetoglobosin I,P450氧化酶(CHGG_01242-1)负责催化79、cytoglobosin D (82)和chaetoglobosin J (83)的立体特异性氧化,FAD/FMN-单氧化酶(CHGG_ 01242-2)分别催化20-dihydro-chaetoglobosin A (81)的C-20氨基酸基团脱氢和82转化为83,P450双加氧酶(CHGG_01242-3)分别催化79和80的C-19和C-20位的立体特异性双羟基化。

在真菌天然产物生物合成途径中普遍存在Diels-Alder环加成反应,特别是聚酮-非核糖体肽天然产物[52]。在嗜热毁丝菌Myceliophthora thermophile中分离得到Myceliothermophins,包括myceliothermophin E和A (20)[53]。在M. thermophile ATCC 42462中发现了Myceliothermophins的生物合成基因簇Myc,包括PKS-NRPS编码基因(MycA)、DAase编码基因(MycB)和反式烯酰还原酶ER编码基因(MycC),MycAC催化合成含4-吡咯啉-2-酮的无环聚烯烃化合物84[54]。在A. nidulans中异源表达MycABC,未检测到化合物myceliothermophin E,表明C21位的羟基化作用可能被M. thermophila中其他途径的酶催化[55]。Li等通过同源重组技术进行基因(MycABC)的敲除,结果表明细胞毒素20的生物合成途径涉及3个催化酶,其中Diels-Alder加成酶(MycB)催化非环底物形成反式-十氢化萘(图 5C)[56]。MycB分别催化88的C18位酮的Diels-Alder反应形成终产物20和底物85转化为86,MycA负责产生和释放氨酰基聚酮化合物aldehyde (84),Knoevenagel缩合形成ketone (85),87和89在空气中自发氧化分别形成88和20。

5 展望真菌聚酮化合物是临床药用天然产物的主要来源之一,其生物合成基因簇中聚酮合酶能催化简单模块合成结构复杂及多样化的化合物,从而具有重要的生物活性。真菌聚酮化合物生物合成不但涉及普通的生物酶如O-甲基转移酶(AurB、KtnB、PhnC等)、FAD依赖的氧化酶(PhnB、CgsF、GedK等)、P450氧化酶(CgsB、KtnC、CHGG_01242-1等),而且有的还涉及特殊催化功能的酶如Diels-Alder环加成酶(MycB)、双功能酶(AoiQ)和异戊烯基转移酶(PhnF)。因此,真菌聚酮化合物生物合成的研究不仅揭示了应用简单的起始单元产生复杂结构的机制,而且将挖掘出一些具有新颖独特催化作用的生物酶,从而促进聚酮生物活性类似物的发展。目前,部分聚酮化合物由于其生产菌株的致病性,从根本上限制了通过原始生产菌株发酵生产化合物的规模,那么揭示聚酮化合物的生物合成基因簇或生物合成途径有望使其在无致病性模式生物(S. cerevisiae[57]、A. nidulans[58]、A. oryzae[59])中实现异源生产。随着新的真菌基因组序列的丰富,应用一系列生物信息学工具[60-62]在基因组中搜索将会挖掘出更多的真菌聚酮化合物生物合成基因簇,分析这些基因功能将挖掘出新颖的聚酮化合物。真菌聚酮化合物的生物合成研究通常先通过生物信息学分析初步确认负责特定催化反应的基因,从而提出可能的生物合成途径,随后通过遗传操作如靶向基因敲除,异源表达和酶生化反应阐明相关基因的详细催化机制。随着大量生物酶催化作用的揭示,将丰富合成生物学酶的选择性,从而组合不同来源的聚酮合酶如植物、细菌、真菌构建人工代谢途径,从而提供非天然的聚酮化合物。未来,真菌聚酮化合物很可能仍然是新型药物制剂和农业化学品的主要来源,其主要通过真菌本身或合成生物学产生。

| [1] | Butler MS, Robertson AAB, Cooper MA. Natural product and natural product derived drugs in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep, 2014, 31(11): 1612–1661. DOI: 10.1039/C4NP00064A |

| [2] | Hertweck C. The biosynthetic logic of polyketide diversity. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2009, 48(26): 4688–4716. DOI: 10.1002/anie.v48:26 |

| [3] | Turner NW, Subrahmanyam S, Piletsky SA. Analytical methods for determination of mycotoxins: a review. Anal Chim Acta, 2009, 632(2): 168–180. DOI: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.11.010 |

| [4] | Yabe K, Nakajima H. Enzyme reactions and genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2004, 64(6): 745–755. DOI: 10.1007/s00253-004-1566-x |

| [5] | Yin WB, Chooi YH, Smith AR, et al. Discovery of cryptic polyketide metabolites from dermatophytes using heterologous expression in Aspergillus nidulans. ACS Synth Biol, 2013, 2(11): 629–634. DOI: 10.1021/sb400048b |

| [6] | Steyn PS, Vleggaar R, Wessels PL. Biosynthesis of the aurovertins B and D. The role of methionine and propionate in the simultaneous operation of two independent biosynthetic pathways. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1, 1981, 1(4): 1298–1308. |

| [7] | Schümann J, Hertweck C. Molecular basis of cytochalasan biosynthesis in fungi: gene cluster analysis and evidence for the involvement of a PKS-NRPS hybrid synthase by RNA silencing. J Am Chem Soc, 2007, 129(31): 9564–9565. DOI: 10.1021/ja072884t |

| [8] | Betina V. Biological effects of the antibiotic brefeldin A (decumbin, cyanein, ascotoxin, synergisidin): a retrospective. Folia Microbiol, 1992, 37(1): 3–11. DOI: 10.1007/BF02814572 |

| [9] | Newman AG, Vagstad AL, Belecki K, et al. Analysis of the cercosporin polyketide synthase CTB1 reveals a new fungal thioesterase function. Chem Commun, 2012, 48(96): 11772–11774. DOI: 10.1039/c2cc36010a |

| [10] | Gao SS, Duan AB, Xu W, et al. Phenalenone polyketide cyclization catalyzed by fungal polyketide synthase and flavin-dependent monooxygenase. J Am Chem Soc, 2016, 138(12): 4249–4259. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b01528 |

| [11] | Mazzaferro LS, Hüttel W, Fries A, et al. Cytochrome P450-catalyzed regio-and stereoselective phenol coupling of fungal natural products. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(38): 12289–12295. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b06776 |

| [12] | Chen HQ, Lee MH, Daub ME, et al. Molecular analysis of the cercosporin biosynthetic gene cluster in Cercospora nicotianae. Mol Microbiol, 2007, 64(3): 755–770. DOI: 10.1111/mmi.2007.64.issue-3 |

| [13] | Choquer M, Dekkers KL, Chen HQ, et al. The CTB1 gene encoding a fungal polyketide synthase is required for cercosporin biosynthesis and fungal virulence of Cercospora nicotianae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact, 2005, 18(5): 468–476. DOI: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0468 |

| [14] | Choquer M, Lee MH, Bau HJ, et al. Deletion of a MFS transporter-like gene in Cercospora nicotianae reduces cercosporin toxin accumulation and fungal virulence. FEBS Lett, 2007, 581(3): 489–494. DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.011 |

| [15] | Chen HQ, Lee MH, Chung KR. Functional characterization of three genes encoding putative oxidoreductases required for cercosporin toxin biosynthesis in the fungus Cercospora nicotianae. Microbiology, 2007, 153(8): 2781–2790. DOI: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007294-0 |

| [16] | Newman AG, Townsend CA. Molecular characterization of the cercosporin biosynthetic pathway in the fungal plant pathogen Cercospora nicotianae. J Am Chem Soc, 2016, 138(12): 4219–4228. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b00633 |

| [17] | Elsebai MF, Saleem M, Tejesvi MV, et al. Fungal phenalenones: chemistry, biology, biosynthesis and phylogeny. Nat Prod Rep, 2014, 31(5): 628–645. DOI: 10.1039/c3np70088g |

| [18] | Nielsen MT, Nielsen JB, Anyaogu DC, et al. Heterologous reconstitution of the intact geodin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans through a simple and versatile PCR based approach. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(8): e72871. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072871 |

| [19] | Chooi YH, Wang P, Fang JX, et al. Discovery and characterization of a group of fungal polycyclic polyketide prenyltransferases. J Am Chem Soc, 2012, 134(22): 9428–9437. DOI: 10.1021/ja3028636 |

| [20] | Chooi YH, Fang JX, Liu H, et al. Genome mining of a prenylated and immunosuppressive polyketide from pathogenic fungi. Org Lett, 2013, 15(4): 780–783. DOI: 10.1021/ol303435y |

| [21] | Tsunematsu Y, Ichinoseki S, Nakazawa T, et al. Overexpressing transcriptional regulator in Chaetomium globosum activates a silent biosynthetic pathway: evaluation of shanorellin biosynthesis. J Antibiot, 2012, 65(7): 377–380. DOI: 10.1038/ja.2012.34 |

| [22] | Sato M, Yamada H, Hotta K, et al. Elucidation of the shanorellin biosynthetic pathway and functional analysis of associated enzymes. Med Chem Comm, 2015, 6(3): 425–430. DOI: 10.1039/C4MD00352G |

| [23] | Basyouni SHE, Brewer D, Vining LC. Pigments of the genus Beauveria. Can J Bot, 1968, 46(4): 441–448. DOI: 10.1139/b68-067 |

| [24] | Seger C, Längle T, Pernfuss B, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection assay for the detection and quantification of the Beauveria metabolite oosporein from potato tubers. J Chromatogr A, 2005, 1092(2): 254–257. DOI: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.08.069 |

| [25] | Alurappa R, Bojegowda MRM, Kumar V, et al. Characterisation and bioactivity of oosporein produced by endophytic fungus Cochliobolus kusanoi isolated from Nerium oleander L. Nat Prod Res, 2014, 28(23): 2217–2220. DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2014.924933 |

| [26] | Feng P, Shang YF, Cen K, et al. Fungal biosynthesis of the bibenzoquinone oosporein to evade insect immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(36): 11365–11370. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1503200112 |

| [27] | Yu JH, Hamari Z, Han KH, et al. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol, 2004, 41(11): 973–981. DOI: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001 |

| [28] | Gravelat FN, Askew DS, Sheppard DC. Targeted gene deletion in Aspergillus fumigatus using the hygromycin-resistance split-marker approach. Methods Mol Biol, 2012, 845: 119–130. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8 |

| [29] | Mao XM, Zhan ZJ, Grayson MN, et al. Efficient biosynthesis of fungal polyketides containing the dioxabicyclo-octane ring system. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(37): 11904–11907. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b07816 |

| [30] | Zabala AO, Chooi YH, Choi MS, et al. Fungal polyketide synthase product chain-length control by partnering thiohydrolase. ACS Chem Biol, 2014, 9(7): 1576–1586. DOI: 10.1021/cb500284t |

| [31] | Stothers JB, Stoessl A. Confirmation of the polyketide origin of kotanin by incorporation of [1, 2-13C2]. Can J Chem, 1988, 66(11): 2816–2818. DOI: 10.1139/v88-435 |

| [32] | Hüttel W, Müller M. Regio-and stereoselective intermolecular oxidative phenol coupling in kotanin biosynthesis by Aspergillus Niger. ChemBioChem, 2007, 8(5): 521–529. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1439-7633 |

| [33] | Nakazawa T, Ishiuchi K, Praseuth A, et al. Overexpressing transcriptional regulator in Aspergillus oryzae activates a silent biosynthetic pathway to produce a novel polyketide. ChemBioChem, 2012, 13(6): 855–861. DOI: 10.1002/cbic.v13.6 |

| [34] | Chankhamjon P, Tsunematsu Y, Ishida-Ito M, et al. Regioselective dichlorination of a non-activated aliphatic carbon atom and phenolic bismethylation by a multifunctional fungal flavoenzyme. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2016, 55(39): 11955–11959. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201604516 |

| [35] | Wada SI, Usami I, Umezawa Y, et al. Rubratoxin A specifically and potently inhibits protein phosphatase 2A and suppresses cancer metastasis. Cancer Sci, 2010, 101(3): 743–750. DOI: 10.1111/cas.2010.101.issue-3 |

| [36] | Williams K, Szwalbe AJ, Mulholland NP, et al. Heterologous production of fungal maleidrides reveals the cryptic cyclization involved in their biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2016, 55(23): 6784–6788. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201511882 |

| [37] | Bai J, Yan DJ, Zhang T, et al. A cascade of redox reactions generates complexity in the biosynthesis of the protein phosphatase-2 inhibitor rubratoxin A. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2017, 56(17): 4782–4786. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201701547 |

| [38] | Somoza AD, Lee KH, Chiang YM, et al. Reengineering an azaphilone biosynthesis pathway in Aspergillus nidulans to create lipoxygenase inhibitors. Org Lett, 2012, 14(4): 972–975. DOI: 10.1021/ol203094k |

| [39] | Chiang YM, Oakley CE, Ahuja M, et al. An efficient system for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite genes in Aspergillus nidulans. J Am Chem Soc, 2013, 135(20): 7720–7731. DOI: 10.1021/ja401945a |

| [40] | Winter JM, Sato M, Sugimoto S, et al. Identification and characterization of the chaetoviridin and chaetomugilin gene cluster in Chaetomium globosum reveal dual functions of an iterative highly-reducing polyketide synthase. J Am Chem Soc, 2012, 134(43): 17900–17903. DOI: 10.1021/ja3090498 |

| [41] | Szewczyk E, Nayak T, Oakley CE, et al. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Protoc, 2007, 1(6): 3111–3120. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2006.405 |

| [42] | Winter JM, Cascio D, Dietrich D, et al. Biochemical and structural basis for controlling chemical modularity in fungal polyketide biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(31): 9885–9893. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b04520 |

| [43] | Buayairaksa M, Kanokmedhakul S, Kanokmedhakul K, et al. Cytotoxic lasiodiplodin derivatives from the fungus Syncephalastrum racemosum. Arch Pharm Res, 2011, 34(12): 2037–2041. DOI: 10.1007/s12272-011-1205-x |

| [44] | Kashima T, Takahashi K, Matsuura H, et al. Biosynthesis of resorcylic acid lactone (5S)-5-hydroxylasiodiplodin in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Biosci Biotech Biochem, 2009, 73(11): 2522–2524. DOI: 10.1271/bbb.90417 |

| [45] | Xu YQ, Zhou T, Espinosa-Artiles P, et al. Insights into the biosynthesis of 12-membered resorcylic acid lactones from heterologous production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Chem Biol, 2014, 9(5): 1119–1127. DOI: 10.1021/cb500043g |

| [46] | Boettger D, Hertweck C. Molecular diversity sculpted by fungal PKS-NRPS hybrids. ChemBioChem, 2013, 14(1): 28–42. DOI: 10.1002/cbic.201200624 |

| [47] | Maiya S, Grundmann A, Li X, et al. Identification of a hybrid PKS/NRPS required for pseurotin A biosynthesis in the human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. ChemBioChem, 2007, 8(14): 1736–1743. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1439-7633 |

| [48] | Tsunematsu Y, Fukutomi M, Saruwatari T, et al. Elucidation of pseurotin biosynthetic pathway points to trans-acting C-methyltransferase: generation of chemical diversity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2014, 53(32): 8475–8479. DOI: 10.1002/anie.v53.32 |

| [49] | Wiemann P, Guo CJ, Palmer JM, et al. Prototype of an intertwined secondary-metabolite supercluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(42): 17065–17070. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1313258110 |

| [50] | Zou Y, Xu W, Tsunematsu Y, et al. Methylation-dependent acyl transfer between polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase modules in fungal natural product biosynthesis. Org Lett, 2014, 16(24): 6390–6393. DOI: 10.1021/ol503179v |

| [51] | Ishiuchi K, Nakazawa T, Yagishita F, et al. Combinatorial generation of complexity by redox enzymes in the chaetoglobosin A biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc, 2013, 135(19): 7371–7377. DOI: 10.1021/ja402828w |

| [52] | Minami A, Oikawa H. Recent advances of diels-alderases involved in natural product biosynthesis. J Antibiot, 2016, 69(7): 500–506. DOI: 10.1038/ja.2016.67 |

| [53] | Yang YL, Lu CP, Chen MY, et al. Cytotoxic polyketides containing tetramic acid moieties isolated from the fungus Myceliophthora thermophila: elucidation of the relationship between cytotoxicity and stereoconfiguration. Chemistry, 2007, 13(24): 6985–6991. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3765 |

| [54] | Song ZS, Bakeer W, Marshall JW, et al. Heterologous expression of the avirulence gene ACE1 from the fungal rice pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae. Chem Sci, 2015, 6(8): 4837–4845. DOI: 10.1039/C4SC03707C |

| [55] | Tsunematsu Y, Ishikawa N, Wakana D, et al. Distinct mechanisms for Spiro-carbon formation reveal biosynthetic pathway crosstalk. Nat Chem Biol, 2013, 9(12): 818–825. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.1366 |

| [56] | Li L, Yu PY, Tang MC, et al. Biochemical characterization of a eukaryotic decalin-forming diels-alderase. J Am Chem Soc, 2016, 138(49): 15837–15840. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b10452 |

| [57] | Saruwatari T, Yagishita F, Mino T, et al. Cytochrome P450 as dimerization catalyst in diketopiperazine alkaloid biosynthesis. ChemBioChem, 2014, 15(5): 656–659. DOI: 10.1002/cbic.201300751 |

| [58] | Ryan KL, Moore CT, Panaccione DG. Partial reconstruction of the ergot alkaloid pathway by heterologous gene expression in Aspergillus nidulans. Toxins, 2013, 5(2): 445–455. DOI: 10.3390/toxins5020445 |

| [59] | Tagami K, Liu CW, Minami A, et al. Reconstitution of biosynthetic machinery for indole-diterpene paxilline in Aspergillus oryzae. J Am Chem Soc, 2013, 135(4): 1260–1263. DOI: 10.1021/ja3116636 |

| [60] | Yaegashi J, Oakley BR, Wang CCC. Recent advances in genome mining of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters and the development of heterologous expression systems in Aspergillus nidulans. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 41(2): 433–442. DOI: 10.1007/s10295-013-1386-z |

| [61] | Wiemann P, Keller NP. Strategies for mining fungal natural products. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 41(2): 301–313. DOI: 10.1007/s10295-013-1366-3 |

| [62] | Brakhage AA, Schroeckh V. Fungal secondary metabolites—strategies to activate silent gene clusters. Fungal Genet Biol, 2011, 48(1): 15–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.04.004 |

2018, Vol. 34

2018, Vol. 34