中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 王晓娟, 赵春江, 李荷楠, 陈宏斌, 靳龙阳, 王占伟, 廖康, 曾吉, 徐修礼, 金炎, 苏丹虹, 刘文恩, 胡志东, 曹彬, 褚云卓, 张嵘, 罗燕萍, 胡必杰, 王辉

- Wang Xiaojuan, Zhao Chunjiang, Li Henan, Chen Hongbin, Jin Longyang, Wang Zhanwei, Liao Kang, Zeng Ji, Xu Xiuli, Jin Yan, Su Danhong, Liu Wenen, Hu Zhidong, Cao Bin, Chu Yunzhuo, Zhang Rong, Luo Yanping, Hu Bijie, Wang Hui

- 2011年、2013年和2016年医院内获得性血流感染常见病原菌分布及其耐药性分析

- Microbiological profiles of pathogens causing nosocomial bacteremia in 2011, 2013 and 2016

- 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(8): 1205-1217

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2018, 34(8): 1205-1217

- 10.13345/j.cjb.180192

-

文章历史

- Received: May 9, 2018

- Accepted: July 9, 2018

2 中山大学附属第一医院 检验科,广东 广州 510080;

3 华中科技大学同济医学院附属普爱医院 检验科,湖北 武汉 430030;

4 空军军医大学西京医院 检验科,陕西 西安 710032;

5 山东大学附属省立医院 检验科,山东 济南 250012;

6 广州呼吸疾病研究所,广东 广州 510120;

7 中南大学湘雅医院 检验科,湖南 长沙 410013;

8 天津医科大学总医院 检验科,天津 300070;

9 中日友好医院 呼吸与危重症医学科,北京 100029;

10 首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院 检验科 感染与临床微生物科,北京 100020;

11 中国医科大学附属第一医院 检验科,辽宁 沈阳 110122;

12 浙江大学医学院附属第二医院 检验科,浙江 杭州 310009;

13 中国人民解放军总医院 临床微生物科,北京 100039;

14 复旦大学附属中山医院 临床微生物科,上海 200032

2 Department of Clinical Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510080, Guangdong, China;

3 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Puai Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan 430030, Hubei, China;

4 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Xijing Hospital, Air Force Military Medical University, Xi'an 710032, Shaanxi, China;

5 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Jinan 250012, Shandong, China;

6 Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Disease, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510120, Guangdong, China;

7 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan, China;

8 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin 300070, China;

9 Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Center of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital and National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Diseases, Beijing 100029, China;

10 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Beijing Chao Yang Hospital of Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China;

11 Department of Clinical Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110122, Liaoning, China;

12 Department of Clinical Laboratory, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang, China;

13 Department of Clinical Microbiology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing 100039, China;

14 Department of Clinical Microbiology, Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China

抗菌药物耐药已经成为本世纪面临的重大公共卫生问题[1]。随着新型抗菌药物的引入和抗菌药物的广泛应用,多重耐药菌和新药耐药菌[2-3]的分离率呈逐年上升趋势,使有效应用于临床治疗的抗菌药物捉襟见肘。菌血症感染患者,尤其是耐药菌如碳青霉烯耐药革兰阴性杆菌等感染病死率高、疾病负担重[4-5],因而动态监测血流感染病原菌的耐药趋势具有十分重要的临床意义。本研究通过2011年、2013年和2016年度监测14家教学医院参与的中国医院内感染的抗生素耐药监测(Chinese antimicrobial resistance surveillance of nosocomial infection, CARES)项目中血流感染病原菌的分布和耐药性变化,为临床治疗医院内获得性血流感染提供合理用药依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 菌株来源所有医院内获得性血流感染病原菌分离自中国10个城市14家教学医院,共计2 248株病原菌,其中革兰阴性杆菌占73.7% (1 657株/2 248株),革兰阳性球菌占26.3% (591株/2 248株)。2011年收集737株,2013年收集706株,2016年收集805株。14家教学医院中,中山大学附属第一医院收集211株,北京大学人民医院202株,华中科技大学同济医学院附属协和医院199株,空军军医大学西京医院194株,山东大学附属省立医院193株,广州呼吸疾病研究所192株,中南大学湘雅医院186株,天津医科大学总医院185株,首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院176株,中国医科大学附属第一医院132株,浙江大学医学院附属第二医院129株,解放军总医院129株,复旦大学附属中山医院120株。

医院内获得性血流感染定义为入院48 h或48 h以上出现微生物学证实的菌血症感染症状或转院到本院48 h内出现微生物学证实的菌血症感染症状[6-7]。菌株入组标准为血培养首次分离的非重复菌株,并根据收集的临床病例资料表判定为医院内获得性血流感染分离株。14家分中心收集菌株均送至中心实验室北京大学人民医院检验科微生物学实验室进行菌株再鉴定和抗菌药物敏感性试验(以下简称药敏试验)。菌株鉴定采用梅里埃Vitek2-Compact全自动微生物鉴定系统或布鲁克质谱仪(Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry,MALDI-TOF MS)。药敏试验质控菌株采用大肠埃希菌ATCC25922、铜绿假单胞菌ATCC27853、金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC29213和粪肠球菌ATCC29212。

1.2 药敏试验药敏试验使用美国BD公司的Mueller Hinton琼脂,采用琼脂稀释法或微量肉汤稀释法测定抗菌药物的最低抑菌浓度(Minimum inhibitory concentration,MIC),测定的抗菌药物包括头孢西丁、头孢曲松、头孢噻肟、头孢噻肟/克拉维酸(4 μg/mL)、头孢他啶、头孢他啶/克拉维酸(4 μg/mL)、头孢吡肟、头孢哌酮/舒巴坦(2:1)、哌拉西林/他唑巴坦(4 μg/mL)、亚胺培南、美罗培南、环丙沙星、左氧氟沙星、莫西沙星、阿米卡星、替加环素、米诺环素、苯唑西林、氨苄西林、红霉素、克林霉素、万古霉素、替考拉宁、利奈唑胺、复方磺胺甲噁唑/甲氧苄啶(19:1)和庆大霉素。药敏试验方法按照美国临床实验室标准化研究所(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute,CLSI) M07-A10文件(2015年)[8]所推荐的操作方法进行。药敏试验结果解释标准参照CLSI-M100-S26文件(2016年)[9],其中头孢哌酮/舒巴坦、头孢噻肟/克拉维酸和头孢他啶/克拉维酸的折点分别参照头孢哌酮、头孢噻肟和头孢他啶的折点。替加环素的药敏试验操作参照《替加环素体外药敏试验操作规程专家共识》[10-11],折点参照美国食品药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)的标准。粘菌素的折点参照欧洲临床微生物和感染病学会药敏委员会(European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing,EUCAST,http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoins/),≤2 μg/mL为敏感,> 2 μg/mL为耐药。

1.3 重要耐药菌的检测多重耐药(Multidrug resistant,MDR)革兰阴性杆菌定义为体外药敏试验检测结果对临床常规应用的至少三类抗菌药物同时呈现为不敏感(包括中介和耐药)的革兰阴性杆菌;其中铜绿假单胞菌和鲍曼不动杆菌的抗菌药物分类参照泛耐药菌实验室诊断的中国专家共识[1, 12]。超广谱β-内酰胺酶(Extended spectrum β-lactamases,ESBLs)、甲氧西林耐药葡萄球菌(Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp.,MRS)及高水平氨基糖苷类耐药肠球菌(High-level gentamicin resistant,HLGR)的检测参照CLSI推荐检测方法。碳青霉烯不敏感肠杆菌科细菌判定参照CLSI M100-S26文件(2016年)[9],即厄他培南MIC值≥1 μg/mL,或亚胺培南/美罗培南MIC值≥2 μg/mL。

1.4 数据分析药敏试验结果采用Whonet 5.6版本软件(WHONET.org.cn)进行分析。

2 结果与分析 2.1 医院内获得性血流感染病原菌分布2011年、2013年和2016年医院内获得性血流感染分离率前10位病原菌见图 1。如图 1所示,血流感染病原谱仍以革兰阴性杆菌为主,各年度分离优势病原菌占首位分离率的为大肠埃希菌,其次是肺炎克雷伯菌和金黄色葡萄球菌。肠杆菌科细菌共计1 250株,以大肠埃希菌(32.6%,733株/2 248株)和肺炎克雷伯菌(14.5%,327株/2 248株)为主;非发酵菌中鲍曼不动杆菌(8.7%,196株/2 248株)和铜绿假单胞菌(6.2%,140株/2 248株)的分离率最高。革兰阳性球菌以金黄色葡萄球菌(10.0%,225株/2 248株)和屎肠球菌(4.9%,111株/2 248株)为主。

|

| 图 1 2011年、2013年和2016年医院内获得性血流感染分离前10位病原菌 Figure 1 The top 10 isolated nosocomial bacteremia pathogens in 2011, 2013 and 2016. eco: Escherichia coli; kpn: Klebsiella pneumonia; sau: Staphylococcus aureus; aba: Acinetobacter baumannii; pae: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; efm: Enterococcus faecium; ecl: Enterobacter cloacae; sep: Staphylococcus epidermidis; efa: Enterococcus faecalis; pma: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia |

| |

血流感染中革兰阴性杆菌对抗菌药物体外敏感率较高的依次为粘菌素(96.5%,1 525株/1 581株,不包括对粘菌素天然耐药的黏质沙雷菌、变形杆菌属、摩根摩根菌和洋葱伯克霍尔德菌复合体)、替加环素(95.6%,1 375株/1 438株,不包括对替加环素天然耐药的铜绿假单胞菌、摩根摩根菌和变形杆菌属等)、头孢他啶/克拉维酸(89.2%,1 112株/1 246株)、阿米卡星(86.4%,1 382株/1 599株)和美罗培南(85.7%,1 376株/1 605株)。革兰阳性球菌对抗菌药物体外敏感率较高的抗菌药物依次为替考拉宁(100.0%,591株/591株)、达托霉素(100.0%,398株/398株)、万古霉素(99.7%,576株/578株)和利奈唑胺(99.7%,589株/591株)。血流感染中分离率较高的病原菌对抗菌药物敏感率见表 1。

| Antimicrobial agents | Enterobacteriaceae | Staphylococcus spp. | Acinetobacter baumannii | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Enterococcus spp. | ||||||||||||||

| 2011 (n=408) | 2013 (n=402) | 2016 (n=439) | 2011 (n=136) | 2013 (n=132) | 2016 (n=134) | 2011 (n=12) | 2013 (n=52) | 2016 (n=12) | 2011 (n=51) | 2013 (n=35) | 2016 (n=54) | 2011 (n=51) | 2013 (n=59) | 2016 (n=73) | |||||

| Colistin | 98.5% | 98.2% | 93, 9% | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | - | - | - | ||||

| Tigecycline | 983% | 97.7% | 96.8% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 68.1% | 923% | 91.7% | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||||

| Imipenem | 97.8% | 96.0% | 95.9% | ND | ND | ND | 26.4% | 17.3% | 12.5% | 86.3% | 65.7% | 64.8% | - | - | - | ||||

| Meropenem | 97.8% | 96.5% | 95.9% | ND | ND | ND | 25.0% | 17.3% | 12.5% | 92.2% | 74.3% | 77.8% | - | - | - | ||||

| Cefoperazone/sulbactam | 71.8% | 84.3% | 85.0% | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 88.2% | 92.8% | 90, 7% | ND | ND | ND | 22.2% | 173% | 13.9% | 94.1% | 71.4% | 83.3% | — | — | — | ||||

| Cefepime | 77.0% | 76.3% | 67.0% | ND | ND | ND | 23.6% | 17.3% | 15.3% | 96.1% | 74.3% | 81.5% | - | - | - | ||||

| Ceftazidime | 63.0% | 68.2% | 72.0% | ND | ND | ND | 27.8% | 19.2% | 15.3% | 94.1% | 74.3% | 81.5% | - | - | - | ||||

| Ceftazidime/clavulanic acid | 87.9% | 91.0% | 88.8% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Cefotaxime | 40.4% | 43.8% | 50.6% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Cefotaxime/clavulanic acid | 83.3% | 89.1% | 85.9% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Ceftriaxone | 45.3% | 42.5% | 50.3% | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Cefoxitin | 59.4% | 72.3% | 72.1% | 48.1% | 70.3% | 68.3% | ND | NA | NA | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Levofloxacin | 47.1% | 56.7% | 55.4% | 44.1% | 56.8% | 62.7% | 22.2% | 17.3% | 15.3% | 94.1% | 88.6% | 81.5% | 26.3% | 23.7% | 43.8% | ||||

| Amikacin | 90.9% | 96.8% | 95.0% | ND | ND | ND | 36.1% | 21.2% | 30.6% | 94.1% | 91.4% | 96.3% | - | - | - | ||||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | ND | ND | ND | 83.1% | 76.5% | 88.1% | ND | ND | ND | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Vancomycin | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100.0% | 98.1% | 98.5% | ||||

| Teicoplanin | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||||

| Linezolid | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.3% | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 98.6% | ||||

| Daptomycin | - | - | - | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||||

| Erythromycin | - | - | - | 22.2% | 39.4% | 24.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||||

| "-":breakpoints were not available according to CLSI Ml00-S26 document; ND: not detected. | |||||||||||||||||||

替加环素、粘菌素、碳青霉烯类和氨基糖苷类抗菌药物对肠杆菌科细菌保持较高的体外抗菌活性(敏感率 > 90.0%)。血流感染中分离率最高的大肠埃希菌和肺炎克雷伯菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感性见表 2。表 2分别列出了2011年、2013年和2016年产ESBLs菌株、不产ESBLs菌株和不能确定是否产ESBLs的菌株[对头孢噻肟(≥2 μg/mL)和/或头孢他啶(≥8 μg/mL)不敏感,加克拉维酸后MIC不降低或降低倍数 < 8倍]。2011年、2013年和2016年ESBLs发生率分别为50.6% (206株/407株)、49.8% (136株/273株)和38.9% (167株/429株)。碳青霉烯不敏感肠杆菌科细菌中肺炎克雷伯菌居首位,占57.1% (24株/42株),其次是大肠埃希菌(16.7%,7株/42株)和产酸克雷伯菌(11.9%,5株/42株) (表 3)。肠杆菌科细菌中有30株菌对替加环素不敏感,其中肺炎克雷伯菌占76.7% (23株/30株);21株替加环素耐药肺炎克雷伯菌对碳青霉烯类抗菌药物敏感。分离出粘菌素耐药肠杆菌科细菌为39株,其中大肠埃希菌为17株(占43.6%),阴沟肠杆菌为14株(占35.9%),肺炎克雷伯菌为6株(15.4%)。

| Antimicrobial agents | E. coli | K. pneumoniae | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-ESBLs | ESBLs | Uncertainty | Non-ESBLs | ESBLs | Uncertainty | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2011(n=75) | 2013(n=57) | 2016(n=117) | 2011(n=156) | 2013(n=156) | 2016(n=156) | 2011(n=156) | 2013(n=4) | 2016(n=2) | 2011(n=64) | 2013(n=39) | 2016(n=65) | 2011(n=40) | 2013(n=23) | 2016(n=32) | 2011(n=6) | 2013(n=5) | 2016(n=13) | ||||||

| Colistin | 98.7% | 100.0% | 98.3% | 99.4% | 97.2% | 92.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.5% | 97.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 94.1% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||||

| Tigecycline | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 99.4% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 98.4% | 94.9% | 94.0% | 90.0% | 95.7% | 79.4% | 100.0% | 80.0% | 92.3% | |||||

| Imipenem | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Meropenem | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.5% | 100.0% | 97.1% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Cefoperazone/sulbactam | 93.4% | 87.7% | 97.5% | 52.9% | 78.3% | 82.3% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 93.8% | 100.0% | 97.0% | 62.5% | 78.3% | 61.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 92.1% | 93.0% | 95.8% | 91.1% | 97.2% | 97.6% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 93.8% | 97.5% | 98.5% | 82.5% | 91.3% | 88.2% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Cefepime | 92.1% | 87.7% | 95.0% | 58.0% | 71.4% | 31.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 96.9% | 97.5% | 97.0% | 80.0% | 65.2% | 23.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Ceftazidime | 86.8% | 82.5% | 86.7% | 44.6% | 46.2% | 54.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 90.6% | 90.0% | 92.5% | 55.0% | 47.8% | 55.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Cefotaxime | 84.2% | 77.2% | 85.0% | 1.9% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 90.6% | 90.0% | 92.5% | 7.5% | 8.7% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 84.2% | 75.4% | 84.2% | 5.7% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 92.2% | 90.0% | 94.0% | 20.0% | 4.3% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Cefoxitin | 72.4% | 73.7% | 75.8% | 42.0% | 70.8% | 71.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 81.3% | 77.5% | 83.6% | 75.0% | 78.3% | 61.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.7% | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 50.0% | 57.9% | 56.7% | 15.9% | 21.7% | 24.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 85.9% | 90.0% | 91.0% | 57.5% | 73.9% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 60.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 47.4% | 52.6% | 55.8% | 15.9% | 16.0% | 23.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 84.4% | 90.0% | 91.0% | 55.0% | 69.6% | 38.2% | 0.0% | 40.0% | 0.0% | |||||

| Moxifloxacin | 48.7% | 60.0% | ND | 16.6% | 20.4% | ND | 0.0% | 0.0% | ND | 85.9% | 91.9% | ND | 57.5% | 75.0% | ND | 0.0% | 50.0% | ND | |||||

| Amikacin | 90.8% | 96.5% | 98.3% | 92.4% | 97.2% | 95.2% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 96.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 82.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 16.7% | 60.0% | 23.1% | |||||

| Minocycine | 76.3% | 82.5% | 75.0% | 67.5% | 66.0% | 73.4% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 79.7% | 80.0% | 82.1% | 30.0% | 39.1% | 17.6% | 33.3% | 40.0% | 46.2% | |||||

| ND: not detected. Uncertainty, indicated isolates were non-susceptible to ceftazidime and/or ceftazidime without MIC values descending or descending less than 8-fold MICs value when adding clavulanic acid correspondently. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Organism | 2011 | 2013 | 2016 | Total (%) |

| kpn | 6 (66.7%) | 5 (31.3%) | 13 (76.5%) | 24 (57.1) |

| eco | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (11.8%) | 7 (16.7) |

| kox | 0 | 5 (31.3%) | 0 | 5 (11.9) |

| ecl | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 3 (7.1) |

| cfr | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 | 2 (4.8) |

| sma | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (2.4) |

| kpn: Klebsiella pneumoniae; eco: Escherichia coli; kox: K. oxytoca; ecl: Enterobacter cloacae; cfr: Citrobacter freundii; sma: Serratia marcescens. | ||||

鲍曼不动杆菌和铜绿假单胞菌是医院内获得性血流感染分离率最高的非发酵菌。鲍曼不动杆菌和铜绿假单胞菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感性见表 1。除粘菌素和替加环素外,鲍曼不动杆菌对其他类抗菌药物的敏感性呈逐年下降趋势,2016年鲍曼不动杆菌对碳青霉烯类抗菌药物的敏感性降至12.5%,其对其他β-内酰胺类和喹诺酮类敏感率低于20.0%,对阿米卡星的敏感率降至30.6%。哌拉西林/他唑巴坦、头孢他啶、头孢吡肟、碳青霉烯类、喹诺酮类和氨基糖苷类抗菌药物对铜绿假单胞菌具有较高的体外抗菌活性(> 70.0%)。

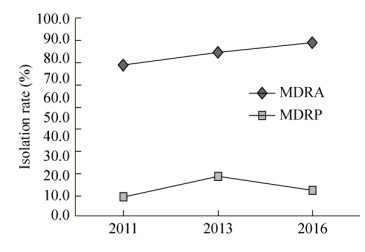

2011年、2013年和2016年多重耐药菌分离率见图 2。如图 2所示,多重耐药鲍曼不动杆菌的分离率呈逐年递增趋势,由2011年76.4% (55株/72株)上升至2016年87.5% (63株/72株)。而多重耐药铜绿假单胞菌分离率相比于鲍曼不动杆菌较低,低于20.0%。

|

| 图 2 2011–2016年医院内获得性血流感染多重耐药菌的分离率比较 Figure 2 The prevalence rates of multidrug-resistant organism from nosocomial bloodstream infections during 2011–2016. MDRA: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; MDRP: multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| |

万古霉素、替考拉宁、利奈唑胺、达托霉素和替加环素对葡萄球菌属细菌的抗菌活性较好(敏感率 > 98.0%) (表 1)。葡萄球菌属中金黄色葡萄球菌为医院内获得性血流感染分离率最高的革兰阳性球菌(图 1),其中甲氧西林耐药金黄色葡萄球菌(Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,MRSA)分离率为38.2% (86株/225株);2011年、2013年和2016年MRSA的分离率呈下降趋势,分别为51.9% (41株/79株)、29.7% (19株/64株)和31.7% (26株/82株) (表 4)。而甲氧西林耐药凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌(Methicillin-resistant coagulase- negative Staphylococcus spp., MRSCoN)分离率为80.6% (141株/175株);2011年、2013年和2016年MRSCoN分离率分别为80.4% (45株/56株)、77.9% (53株/68株)和84.3% (43株/51株) (表 4)。表 4列出甲氧西林耐药和甲氧西林敏感葡萄球菌属细菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感率,可以看出甲氧西林敏感葡萄球菌属细菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感性高于甲氧西林耐药菌株。2016年分离出一株对利奈唑胺耐药的科氏葡萄球菌,其同时也是MRSCoN,但仍对达托霉素、替加环素、米诺环素和利福平保持敏感。

| Antimicrobial agents | S. aureus | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. | |||||||||||||

| MRSA | MSSA | MRSCoN | MSSCoN | ||||||||||||

| 2011 (n=41) | 2013 (n=19) | 2016 (n=26) | 2011 (n=38) | 2013 (n=45) | 2016 (n=56) | 2011 (n=45) | 2013 (n=53) | 2016 (n=43) | 2011 (n=11) | 2013 (n=15) | 2016 (n=8) | ||||

| Linezolid | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | |||

| Daptomycin | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Tigecycline | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Vancomycin | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Teicoplanin | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Minocycline | 73.2% | 57.9% | 69.2% | 94.7% | 100.0% | 96.4% | 100.0% | 96.2% | 95.5% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 7.3% | 21.1% | 42.3% | 84.2% | 82.2% | 83.9% | 31.1% | 35.8% | 31.8% | 81.8% | 80.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Levofloxacin | 7.3% | 21.1% | 46.2% | 89.5% | 88.9% | 89.3% | 31.1% | 35.8% | 31.8% | 81.8% | 80.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 7.3% | 21.1% | 46.2% | 89.5% | 88.9% | 91.1% | 55.6% | 45.3% | 38.6% | 81.8% | 86.7% | 100.0% | |||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 90.2% | 84.2% | 96.2% | 97.4% | 100.0% | 98.2% | 60.0% | 50.9% | 68.2% | 100.0% | 86.7% | 100.0% | |||

| Erythromycin | 2.4% | 21.1% | 3.8% | 57.9% | 64.4% | 46.4% | 9.1% | 18.9% | 6.8% | 27.3% | 60.0% | 37.5% | |||

| Chloramphenicol | 92.7% | 94.7% | 84.6% | 94.7% | 93.3% | 100.0% | 75.6% | 79.2% | 88.6% | 90.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Rifampicin | 43.9% | 42.1% | 80.8% | 97.4% | 100.0% | 98.2% | 91.1% | 82.0% | 90.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| MRSA: Methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA: Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; MRSCoN: Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp.; MSSCoN:Methicillin-susceptible coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp.; ND: not detected. | |||||||||||||||

医院内获得性血流感染中,肠球菌属细菌分离率为8.4% (189株/2 248株)。万古霉素、替考拉宁、利奈唑胺、达托霉素和替加环素对肠球菌属细菌的抗菌活性较好(敏感率 > 98.0%) (表 1)。表 5列出2011年、2013年和2016年医院内获得性血流感染中屎肠球菌和粪肠球菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感率。除米诺环素外,粪肠球菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感性高于屎肠球菌(表 5),其中粪肠球菌对氨苄西林的敏感率高于70.0%。屎肠球菌和粪肠球菌高水平庆大霉素耐药肠球菌的分离率分别为43.2% (48株/111株)和40.9% (27株/66株)。2016年分离的1株利奈唑胺耐药屎肠球菌,其对喹诺酮类药物耐药,但对万古霉素、替考拉宁、替加环素和米诺环素仍保持敏感。2013年和2016年分别分离出1株万古霉素耐药粪肠球菌和1株万古霉素耐药屎肠球菌,其对喹诺酮类药物耐药,但仍对利奈唑胺、替考拉宁、替加环素和米诺环素保持敏感。

| Antimicrobial agents | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus faecalis | |||||

| 2011 (n=35) | 2013 (n=33) | 2016 (n=42) | 2011 (n=22) | 2013 (n=20) | 2016 (n=24) | ||

| Linezolid | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Daptomycin | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | ND | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Tigecycline | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Vancomycin | 100.0% | 100.0% | 97.7% | 100.0% | 95.0% | 100.0% | |

| Teicoplanin | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Ampicillin | 20.6% | 13.3% | 11.6% | 90.5% | 78.9% | 91.3% | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 11.4% | 3.0% | 9.3% | 36.4% | 40.0% | 75.0% | |

| Levofloxacin | 14.3% | 12.1% | 11.6% | 45.5% | 40.0% | 87.5% | |

| Erythromycin | 11.4% | 9.1% | 11.6% | 18.2% | 20.0% | 29.2% | |

| Minocycline | 54.3% | 45.5% | 62.8% | 27.3% | 65.0% | 37.5% | |

| ND: not detected. | |||||||

血流感染病原谱中革兰阴性杆菌分离率高于革兰阳性球菌。而多重耐药革兰阴性杆菌可水平传播耐药性、临床治疗策略有限、病死率较高[13-14],其引起的临床感染已成为危及全球的公共卫生问题。大肠埃希菌和肺炎克雷伯菌是菌血症分离率最高的两种病原菌,其对粘菌素、替加环素、碳青霉烯类和氨基糖苷类抗菌药物保持较高的体外抗菌活性。产ESBLs菌株的耐药性明显高于非产ESBLs菌株。产ESBLs肠杆菌科细菌分离率高达40.7%,而产ESBLs大肠埃希菌明显多于产ESBLs肺炎克雷伯菌。产ESBLs大肠埃希菌和肺炎克雷伯菌对头孢他啶的敏感性高于头孢噻肟的敏感性,提示中国流行blaCTX-M型β-内酰胺酶[15]是这类菌株对三代头孢菌素或四代头孢菌素耐药最主要的原因。碳青霉烯类抗菌药物是治疗产ESBLs革兰阴性杆菌的最后一道防线。自1996年美国首次报道产KPC-2型碳青霉烯酶的肺炎克雷伯菌[16]以来,碳青霉烯不敏感革兰阴性杆菌分离率呈逐年上升趋势[17]。产碳青霉烯酶已成为我国碳青霉烯不敏感肠杆菌科细菌最主要的耐药机制,而KPC-2型酶为流行的主要酶基因型,其次为2009年新发现的NDM型碳青霉烯酶[18]。本研究医院内获得性血流感染中碳青霉烯不敏感肠杆菌科细菌的年度分离率虽然低于6.0%,但基于本课题组前期研究得出我国碳青霉烯耐药肠杆菌科细菌(Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,CRE)的主要耐药基因具有可水平转移特征,警示临床一旦出现CRE感染,应高度重视并予以感控。

替加环素和粘菌素是治疗CRE等多重耐药菌的挽救性治疗措施[19]。然而,临床已相继报道分离出替加环素不敏感菌株,替加环素耐药机制与RND外排泵表达上调相关[20]。本研究中分离的30株替加环素不敏感肠杆菌科细菌对碳青霉烯类抗菌药物敏感性高达93.3% (28株/30株),而分离的42株碳青霉烯不敏感肠杆菌科细菌对替加环素保持较高的敏感性(95.2%,40株/42株),提示临床治疗碳青霉烯耐药菌和替加环素耐药菌时可分别用替加环素和碳青霉烯类抗菌药物覆盖。粘菌素在中国虽未上市,但本研究已分离出39株粘菌素耐药肠杆菌科细菌。随着可水平转移的粘菌素耐药基因mcr-1及其他mcr基因亚型的发现[21-22],同时携带碳青霉烯酶和mcr-1基因临床菌株的报道[23],这将使临床在面对多重耐药菌、泛耐药菌或全耐药菌治疗时真正面临无药可用的艰难境地。

血流感染非发酵菌中以铜绿假单胞菌和鲍曼不动杆菌为主,两类菌中MDR分离率呈上升趋势。铜绿假单胞菌对各类抗菌药物的敏感性优于鲍曼不动杆菌,但Thaden等前瞻性队列研究发现铜绿假单胞菌导致的菌血症病死率高于金黄色葡萄球菌或者其他革兰阴性杆菌所致的菌血症[24],可能与铜绿假单胞菌毒力和易形成生物膜相关。Guo等发现菌株多重耐药表型是鲍曼不动杆菌所致菌血症30 d病死率的独立危险因素[25]。本研究发现菌血症来源的鲍曼不动杆菌对包括碳青霉烯在内的β-内酰胺类、喹诺酮类和氨基糖苷类的敏感性呈下降趋势,分离的鲍曼不动杆菌中大于80.0%的菌株为MDRA,这对临床抗感染治疗工作带来巨大的困难。尽管如此,鲍曼不动杆菌对粘菌素和替加环素敏感性仍高于90.0%,但粘菌素毒副作用大,替加环素血药浓度低,替加环素耐药临床菌株的分离使得鲍曼不动杆菌所致菌血症的抗感染治疗捉襟见肘。

本研究发现MRSA的分离率呈逐年下降趋势,由2011年的51.9%的分离率,2016年降至31.7%;而MRSCoN的分离率一直处于较高水平(高于75.0%)。而高水平庆大霉素耐药肠球菌,分离率为41.8%。葡萄球菌属和肠球菌属对万古霉素、替考拉宁、利奈唑胺、达托霉素和替加环素保持较高的敏感性,然而本研究相继分离出1株利奈唑胺耐药的科氏葡萄球菌和1株利奈唑胺耐药屎肠球菌,1株万古霉素耐药粪肠球菌和1株万古霉素耐药屎肠球菌,高度警示临床需密切关注新出现的耐药菌,亟需深入研究其分子耐药机制和动态监测其对各类抗菌药物的敏感性。

目前我国2011年、2013年和2016年血流感染病原谱构成比无差异,大肠埃希菌、肺炎克雷伯菌和金黄色葡萄球菌仍是菌血症感染最主要的病原菌。除鲍曼不动杆菌对常用抗菌药物的体外敏感性呈逐年下降趋势外,其余病原菌对常用抗菌药物的敏感率上下浮动幅度较小。但仍需高度警惕多重耐药菌、超广谱抗菌药物(碳青霉烯类、替加环素、粘菌素、利奈唑胺和万古霉素)耐药菌,尤其对可水平转移传播的耐药性予以防控;同时,动态监测血流感染病原菌对常用抗菌药物的体外敏感性,为临床合理应用抗菌药物、减缓耐药性的发生、发展提供支撑。

| [1] | Chinese XDR Consensus Working Group. Laboratory diagnosis, clinical management and infection control of the infections caused by extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli: a Chinese consensus statement. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2016, 22(S1): S15–S25. |

| [2] | Wang RB, van Dorp L, Shaw LP, et al. The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nat Commun, 2018, 9: 1179. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03205-z |

| [3] | Chen HB, Wu WJ, Ni M, et al. Linezolid-resistant clinical isolates of enterococci and Staphylococcus cohnii from a multicentre study in China: molecular epidemiology and resistance mechanisms. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2013, 42(4): 317–321. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.06.008 |

| [4] | Morrill HJ, Pogue JM, Kaye KS, et al. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2015, 2(2): ofv050. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofv050 |

| [5] | Prabaker K, Weinstein RA. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units in the United States. Curr Opin Crit Care, 2011, 17(5): 472–479. DOI: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834a4b03 |

| [6] | Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control, 2008, 36(5): 309–332. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 |

| [7] | Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections//Olmsted RN. APIC infection Control and Applied Epidemiology: Principles and Practice. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996: A-1–A-20. |

| [8] | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; Approved standard, 10th ed. CLSI document M07-A10. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2015. |

| [9] | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI document M100-S26. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2016. |

| [10] |

Wang H, Yu YS, Wang MG, et al. Operating procedures for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for tigecycline: a Chinese expert consensus statement.

Chin J Lab Med, 2013, 36(7): 584–587.

(in Chinese). 王辉, 俞云松, 王明贵, 等. 替加环素体外药敏试验操作规程专家共识. 中华检验医学杂志, 2013, 36(7): 584-587. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-9158.2013.07.004 |

| [11] |

Wang H. Correction: Operating procedures for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for tigecycline: a Chinese expert consensus statement.

Chin J Lab Med, 2015, 368(8): 569.

(in Chinese). 王辉. 对《替加环素体外药敏试验操作规程专家共识》一文的更正. 中华检验医学杂志, 2015, 368(8): 569. DOI:10.3760/j.issn.1009-9158.2015.08.018 |

| [12] | Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2012, 18(3): 268–281. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x |

| [13] | Kaye KS, Pogue JM. Infections caused by resistant gram-negative bacteria: epidemiology and management. Pharmacotherapy, 2015, 35(10): 949–962. DOI: 10.1002/phar.2015.35.issue-10 |

| [14] | Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JDD. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2015, 28(3): 565–591. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00116-14 |

| [15] | Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2017, 72(8): 2145–2155. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkx146 |

| [16] | Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13(9): 785–796. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7 |

| [17] | Logan LK, Weinstein RA. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. J Infect Dis, 2017, 215(S1): S28–S36. |

| [18] | Jean SS, Hsueh PR. High burden of antimicrobial resistance in Asia. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2011, 37(4): 291–295. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.01.009 |

| [19] | Alhashem F, Tiren-Verbeet NL, Alp E, et al. Treatment of sepsis: what is the antibiotic choice in bacteremia due to carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae?. World J Clin Cases, 2017, 5(8): 324–332. DOI: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.324 |

| [20] | Pournaras S, Koumaki V, Spanakis N, et al. Current perspectives on tigecycline resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: susceptibility testing issues and mechanisms of resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2016, 48(1): 11–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.04.017 |

| [21] | Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016, 16(2): 161–168. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 |

| [22] | Sun J, Zhang HM, Liu YH, et al. Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol, 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006 |

| [23] | Zhang YW, Liao K, Gao H, et al. Decreased fitness and virulence in ST10 Escherichia coli harboring blaNDM-5 and mcr-1 against a ST4981 strain with blaNDM-5. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2017, 7: 242. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00242 |

| [24] | Thaden JT, Park LP, Maskarinec SA, et al. Results from a 13-Year prospective cohort study show increased mortality associated with bloodstream infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa compared to other bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017, 61(6): e02671–16. |

| [25] | Guo NH, Xue WC, Tang DH, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of hospitalized patients with blood infections caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex in a hospital of Northern China. Am J Infect Control, 2016, 44(4): e37–e39. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.019 |

2018, Vol. 34

2018, Vol. 34