中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 曲戈, 朱彤, 蒋迎迎, 吴边, 孙周通

- Qu Ge, Zhu Tong, Jiang Yingying, Wu Bian, Sun Zhoutong

- 蛋白质工程:从定向进化到计算设计

- Protein engineering: from directed evolution to computational design

- 生物工程学报, 2019, 35(10): 1843-1856

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2019, 35(10): 1843-1856

- 10.13345/j.cjb.190221

-

文章历史

- Received: May 29, 2019

- Accepted: July 17, 2019

- Published: August 20, 2019

2. 中国科学院微生物研究所,北京 100101

2. Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China

地球生命历经40亿年的自然进化,孕育了无数功能丰富、结构复杂的蛋白质,但天然的蛋白质在稳定性、耐受性、选择性等方面往往无法满足工业生产的需求,促使人类探索高效的蛋白质改造方法。蛋白质的三维结构决定其生物学功能,而三维结构又由其内在的氨基酸序列决定。蛋白质的序列空间极为庞大,以一条100个氨基酸长度的蛋白质为例,每个位点可以突变成20种天然氨基酸,它的序列空间达到20100 (约10130),这一数字甚至超过了宇宙中所包含原子的总和[1]。因此,自然界需要花费数百万年来进化得到具有新功能的蛋白质,人类要想获得性能优异的酶还得依靠自身的智慧[2]。

20世纪80年代,聚合酶链式反应(Polymerase chain reaction, PCR)技术的出现为人类改造蛋白质结构提供了高效的分子操作手段,蛋白质工程应运而生。研究者运用PCR技术在基因特定位点引入突变,从而改变蛋白质对应位置的氨基酸残基种类。最初的蛋白质设计案例中,由于彼时缺少蛋白结构与机理研究,突变位点的选择完全依靠研究人员的经验,因此是一种初级理性设计策略,适用性较窄[3]。在此背景下,定向进化(Directed evolution)策略诞生,该技术通过对蛋白质进行多轮突变、表达和筛选,引导蛋白质的性能朝着人们需要的方向进化,从而大幅缩短蛋白质进化的过程[4]。在这之后,定向进化与理性设计结合,形成了半理性设计(Semi-rational design)策略,旨在构建“小而精”的突变体文库,进一步提高效率。近年来,随着结构生物学、计算生物学及人工智能技术的迅猛发展,计算机辅助蛋白质设计(Computer-assisted protein design, CPD)策略为蛋白质工程领域注入了新的学术思想和技术手段,出现了基于结构模拟与能量计算来进行蛋白质设计的新方法,以及使用人工智能(Artificial intelligence, AI)技术指导蛋白质改造的新思路。总体来看,蛋白质工程经历了从初级理性设计、定向进化、半理性设计,再到计算设计的发展历程(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 蛋白质工程发展历程 Fig. 1 Development of protein engineering. |

| |

为了加速蛋白质的进化,定向进化这一策略在20世纪80-90年代被开发出来,通过位点饱和突变(Saturation mutagenesis, SM)、易错PCR (Error-prone polymerase chain reaction, epPCR)及DNA重组(DNA shuffling)等技术,可有效产生序列多样性的随机突变体文库,表达并筛选特定性状提高的目标突变体。将这一过程重复数轮,通过连续积累有益突变,最终可成功获得性能改进或具有新功能的蛋白质[3]。定向进化是一种工程化的改造思路,不需要事先了解结构信息及催化机制,通过迭代有益突变,实现蛋白质性能的飞跃。2018年诺贝尔化学奖得主Frances H. Arnold团队在这一领域作出了杰出贡献,其团队通过使用随机突变及单点饱和突变策略改造P450氧化酶,实现了碳-硅成键[5]、碳-硼成键[6]、烯烃反马氏氧化[7]、卡宾及氮宾的碳-氢键插入[8-9]等一系列令人瞩目的成果。

定向进化技术在工业化应用领域也扮演了重要角色。例如美国Codexis公司通过对羰基还原酶和卤醇脱卤酶进行定向改造,实现降胆固醇药物立普妥关键手性砌块的产业化生产[10];Codexis联合默克公司(现已合并)对转氨酶进行多轮定向进化,实现不对称氨化合成Ⅱ型糖尿病治疗药物西他列汀的工业化应用[11];近年来,华东理工大学许建和团队通过基因挖掘及定向进化羰基还原酶,实现了(R)-硫辛酸的绿色制造工艺[12]。

1.2 半理性设计全随机突变策略是以随机的方式引入突变,它的瓶颈在于突变体文库的规模非常大,不利于筛选。借助蛋白质保守位点及晶体结构分析,通过非随机的方式选取若干个氨基酸位点作为改造靶点,并结合有效密码子的理性选用,构建“小而精”的突变体文库是克服这一瓶颈的有效方式,这种方式被称为半理性设计。20世纪90年代,Manfred T. Reetz教授在酶的不对称催化改造工作中发现影响手性选择的氨基酸位点主要集中在底物结合口袋区域,在此基础上开发了组合活性中心饱和突变策略(Combinatorial active-site saturation test, CAST)及迭代饱和突变技术(Iterative saturation mutagenesis, ISM),广泛应用于酶的立体/区域选择性、催化活力、热稳定性等酶参数的改造[10-15]。例如通过CAST/ISM策略对P450-BM3单加氧酶进行改造,并与醇脱氢酶或过氧化物酶偶联,使其成功应用于高附加值手性二醇及衍生物的不对称催化合成[16-17]。最近,Reetz教授与吴起团队合作,在有效密码子的选取方面作了改进,提出Focused Rational Iterative Site-specific Mutagenesis (FRISM)策略,并应用于南极假丝酵母脂肪酶B (CALB)的不对称催化,成功获得了双手性中心底物所对应的全部4种异构体,且选择性均在90%以上[18]。

在CAST基础上,孙周通等通过理性选择3种氨基酸密码子作为饱和突变的构建单元,开发了三密码子饱和突变技术TCSM (Triple code saturation mutagenesis),进一步降低了筛选工作量[19-20]。除此之外,Gjalt W. Huisman团队基于统计学方法开发的ProSAR (Protein sequence activity relationships)[21]及Miguel Alcalde团队基于序列同源性开发的MORPHING (Mutagenic organized recombination process by homologous in vivo grouping)[22]工具也广泛应用于蛋白酶的设计改造。其他半理性设计策略及应用已在前文进行过评述[23]。基于笔者经验,半理性设计是建立在已有知识(如保守序列、晶体结构、催化机制、通量筛选方法、前期实验数据等)的基础上,对目标蛋白进行再设计。因此,前期基础的丰富程度直接影响到半理性设计的成功与否。

2 计算机辅助蛋白质设计 2.1 概述随着计算机运算能力持续提升、先进算法相继涌现,以及蛋白质序列特征、三维结构、催化机制之间关系不断被挖掘和解析,计算机辅助蛋白质设计策略得到前所未有的重视和发展,人类迎来了蛋白质从头设计的时代[24-25]。蛋白质计算设计一般以原子物理、量子物理、量子化学揭示的微观粒子运动、能量与相互作用规律为理论基础,也有部分研究以统计能量函数为算法依据。研究者在计算机的辅助下,通过运用分子对接(Molecular docking)、分子动力学模拟(Molecular dynamic simulations)、量子力学(Quantum mechanics)方法、蒙特卡罗(Monte Carlo)模拟退火(Simulated annealing)等一系列计算方法(相关方法及使用已有文章综述[26]),预测并评估数以千计的突变体在结构、自由能、底物结合能等方面的变化。基于计算结果,从中筛选可能符合改造要求的突变体并进行实验验证(如突变体能否正常表达、折叠及行使预期功能等);再根据实验结果制定下一轮计算方案,循环往复直到获得符合需求的酶(图 2)。与定向进化相比,蛋白质计算设计可提供明确的改造方案,大幅降低建立、筛选突变体文库所需的工作量,目前已在蛋白质从头设计、酶的底物选择性与热稳定性设计等方面取得了众多成果,更有部分成果达到了工业应用水平[27-28]。

|

| 图 2 计算机辅助蛋白质设计流程 Fig. 2 The workflow of computer-assisted protein design. |

| |

蛋白质的从头设计于2016年被Science杂志列入年度十大科学突破[29],其目标是创造自然界不存在的、可成功折叠的蛋白质并赋予其特定功能,在开发新型病毒疫苗[30-32]、进行肿瘤治疗[33]等领域发挥作用。1997年,Stephen L. Mayo团队提出了包括设计、模拟、实验和分析四步的蛋白质设计策略PDA (Protein design automation)并开发了相应的软件,以锌指结构域为模板成功设计了一个由28个氨基酸组成的ββα蛋白,其核磁检测结构与预测结构高度一致[34]。2003年,华盛顿大学的David Baker团队设计并构建了一个非天然结构模板[35],为蛋白质设计领域开辟了新的方向,其开发的Rosetta软件如今已发展为集蛋白质从头设计、酶活性中心设计、配体对接、生物大分子结构预测等功能为一体的生物大分子计算建模与分析软件组合[36]。目前该程序中最常用的工具包括用于设计蛋白质骨架氨基酸序列的Rosetta Design,以及用于评估序列变化对蛋白质稳定性影响的Rosetta DDG等[37-38]。

表 1总结了最近十年蛋白质从头设计的部分案例。大部分案例采用了基于Rosetta的设计策略,其中最具代表性的便是Baker团队提出的“Inside- out”设计策略,该策略的主体流程如下:在催化机理完全明确的前提下,研究者首先运用量子化学方法设计酶的活性中心,确定酶的关键催化基团与底物形成的过渡态构象(Theozyme);然后使用RosettaMatch搜索蛋白质结构数据库,尝试将theozyme与已有蛋白质结构匹配,筛选能维持theozyme构象的蛋白质骨架结构;接下来使用Rosetta Design设计位于活性中心但不直接参与催化的氨基酸,运用基于蒙特卡罗的模拟退火算法进行多轮采样,获得经过优化的完整酶结构;最后制定评分标准,依据过渡态能量、配体位置取向等多项参数评估设计结果,挑选排名靠前的结构开展活性验证实验[39-40]。运用这套策略,Baker团队成功从头设计了多种酶,其中Retro-Aldol反应酶催化的C-C键断裂反应速率比无酶反应体系高出4个数量级[41];Kemp消除反应酶催化的消除反应速率比无酶反应体系高出5个数量级[42];Diels-Alder反应酶可催化两个底物发生[4+2]双烯环加成反应,形成具有两个手性碳原子的产物,对映选择性达到97%[43]。

| New proteins | Programs | Comments | Reference |

| Retro-aldolase | Rosetta | Novel enzyme | [41] |

| Kemp-eliminase | Rosetta | Novel enzyme | [42] |

| bZIP-binding peptides | CLASSY | Specifically binding peptides | [44] |

| Four-helix bundle | SCADS | Selectively binds two chromophores of DPP-Zn | [45] |

| Membrane protein PRIME | Dead End Elimination followed by Monte Carlo sampling | Two non-natural iron diphenylporphyrins | [46] |

| Single-walled carbon nanotube coating with hexameric coiled coil | DEE/A*, MC/SA | Carbon nanotube surface coating | [47] |

| Influenza hemagglutinin binder | Rosetta | High-affinity protein binder | [32] |

| Ankyrin-repeat-based Tyr-Tyr binding between Prb and Pdar | Rosetta | A novel binding pair | [48] |

| Four helix bundle binding a ruthenium-zinc abiological hyperpolarizable chromophore | SCADS | Binder of a abiological chromophore | [49] |

| Binder of the steroid digoxigenin | Rosetta | High-affinity and selectivity | [50] |

| 80-residue three-helix bundle | Rosetta | Antiparallel, untwisted bundles | [51] |

| Water-soluble α-helical barrels | CCBuilder, SOCKET, PoreWalker | Pentameric, hexameric and heptameric α-helical barrels | [52] |

| Four-helix bundle | MaDCaT, Ez | TM transporter | [53] |

| 660-residue contractile sheath protein | Rosetta | de novo model-building approach | [54] |

| Ferredoxin-like folds and Rossmann2×2 folds | Rosetta | Control over overall shape and size | [55] |

| Four-fold symmetric TIM-barrel protein | Rosetta | Atomic-level accuracy | [56] |

| Protein homo-oligomers | Rosetta | Modular hydrogen-bond network-mediated specificity | [57] |

| Conformationally restricted peptides | Rosetta | New generation of peptide-based drugs | [58] |

| CovCore proteins | Rosetta, TERM | Non-natural CovCore protein scaffolds | [59] |

| Non-natural porphyrin binding protein PS1 | Rosetta | Residues 20 Å away from the binding site were considered | [60] |

| 22 660 mini-proteins of 37-43 residues | Rosetta | Targeted influenza haemagglutinin and botulinum neurotoxin B | [61] |

| Helical repeat proteins | Rosetta | Unusually stable short-range interactions | [62] |

| A fluorescenceactivating β-barrel | Rosetta | Design of small-molecule binding activity | [63] |

| Non-local β-sheet protein | Rosetta | Accurate control over the structure and geometry | [64] |

| Self-assembling helical filaments | Rosetta | New multiscale metamaterials | [65] |

| Interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interleukin-5 (IL-15) | Rosetta | Superior therapeutic candidates | [66] |

蛋白质序列从头设计的主要困难是计算模型的精度不够,导致设计成功率低。大量天然蛋白质的已知序列结构数据可用来改善模型精度,乃至建立精度更高的新计算模型。中国科学技术大学刘海燕团队发展了蛋白质序列设计的统计能量模型ABACUS (A backbone based amino acid usage survey)。用其对不同折叠类型的天然蛋白质骨架进行从头序列设计,实验证明这些序列全自动设计的蛋白质能够可溶性表达并正确折叠,对Dv_1ubq、D_1cy5_M2两个蛋白分子的结构解析结果表明其与设计目标高度吻合[67]。之后程序算法进一步优化,加入了范德华能量函数,设计准确率再度提高,原本需要其他策略辅助提高折叠成功率的1r26蛋白分子,也能应用新一代程序一步设计到位[68]。

“Inside-out”设计策略针对的是酶的活性中心以及催化的反应类型,而酶的骨架结构仍采用自然界已有的蛋白质结构,若骨架结构也能从头设计,便能获得完全由人类设计而非自然进化形成的酶[69]。目前,主链骨架设计还更多依赖于基于“规则”的启发式方法,通用计算方法仍在发展之中。在此方面,刘海燕团队提出了建立氨基酸序列待定、只依赖于主链结构的统计能量模型的设计方法,他们已发表的TetraBASE (Tetrahedron- based backbone statistical energy)验证了这条途径原理上是可能的[70]。进一步,他们已发展了基于神经网络统计能量项的SCUBA (Sidechain unspecialized backbone arrangement)模型,能在序列待定情况下进行主链骨架的全柔性设计和连续采样,这类方法的发展将极大拓宽可选蛋白质骨架结构范围。

2.3 酶的底物选择性与热稳定性设计酶对底物的特异选择性一方面避免了各种副反应的发生,但另一方面限制了酶的底物谱。从自然界中挖掘新酶的速度并不能满足生物技术产业快速增长的需求,因此改变酶的底物特异性是蛋白质计算设计的重要应用方向[39]。Baker团队对鸟嘌呤脱氨酶进行改造,运用同源建模和量子化学计算方法设计以三聚氰酸酰胺为底物的活性中心结构,确定关键侧链基团的位置后优化残基所在的loop区序列以保证新活性中心结构的稳定,在删除2个、突变4个氨基酸残基后使得酶对新底物的活性提高约100倍[71]。在另一项工作中,Baker团队使用Rosetta Design与Foldit改造苯甲醛裂解酶的结合口袋,使其催化3分子甲醛聚合形成二羟丙酮反应的活性提高近100倍,为实现核心生物代谢分子磷酸二羟丙酮合成途径的重构打下基础[72]。中国科学院微生物研究所吴边团队则使用Rosetta Design与高通量分子动力学模拟方法对天冬氨酸酶的活性中心进行设计,得到一系列突变体,分别能高效催化巴豆酸、(E)-2-戊烯酸、富马酸单酰胺、(E)-肉桂酸的β-加氨反应,其中巴豆酸β-加氨合成β-氨基丁酸的反应底物浓度可达300 g/L,反应转化率大于99%,立体选择性大于99%,已具有工业生产的潜力[28]。

工业酶时常需要在高温环境下发挥功能,因此提升酶的热稳定性在工业生产方面具有重要意义。荷兰格罗宁根大学的Dick Janssen团队提出了一种运用计算方法提升酶热稳定性的FRESCO策略(Framework for rapid enzyme stabilization by computational libraries),主要流程如下:研究者首先使用Rosetta DDG、FoldX、动态二硫键挖掘、保守序列分析等计算软件或方法,预测能提高蛋白质热稳定性的单点突变;然后通过分子动力学模拟分析单点突变对酶的影响,删除化学角度上不合理或可能提高蛋白质结构灵活度的突变方案;接下来对剩余单点突变方案进行实验验证,表达、纯化突变后的酶并测定熔融温度与催化活性,筛选出热稳定性提高的突变体;最后将一部分单点突变叠加,获得热稳定性大幅提高的多点突变体[73]。该策略指导下的酶改造过程中,需要表达、纯化的单点突变体不超过200个,单点预测成功率大于10%,酶的熔融温度一般可提升20-35 ℃[74]。Janssen团队运用该策略成功地提升了柠檬烯环氧化物水解酶[73]、卤代醇脱卤酶[75]、卤代烷脱卤酶[76]等多种酶的热稳定性,其中以柠檬烯环氧化物水解酶为代表,该酶的熔融温度从50 ℃提升至85 ℃,55 ℃下的半衰期延长250倍,催化活性提高的同时仍保留反应的立体选择性。吴边团队同样运用FRESCO策略,将一种木聚糖酶的熔融温度提升了14 ℃,改造后的酶在70 ℃下反应5 h的产物量相比野生型提高了10倍,为其应用于工业生产打下基础[77]。

2.4 人工智能技术在计算设计中的应用得益于计算速度的大幅提升以及海量数据集的出现,当前人工智能技术的发展如火如荼。在人工智能领域,机器学习(Machine learning)已经成为开发计算机视觉、语音识别、自然语言处理、机器人操控和其他应用范畴的首选方法[78]。近年来,机器学习等人工智能方法也被应用于蛋白质工程,包括Frances H. Arnold、Manfred T. Reetz等定向进化先驱所领导的实验室均涉足机器学习领域,利用其指导蛋白质设计改造[79-80]。

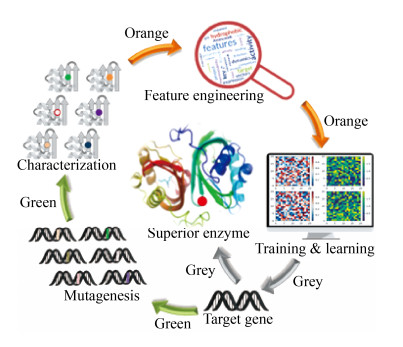

蛋白质突变体及其对应的实验数据本身是无法被机器学习算法直接识别的,其序列、结构、功能等特征(Feature)信息必须以向量或数组的形式展现出来,才能构建被机器学习算法识别的模型。模型的好坏取决于特征提取。以氨基酸在蛋白序列上的位置信息为特征,是比较常见的处理方式;另外,氨基酸残基位点的理化性质(如带电性、亲疏水性、侧链空间体积等)或所处的二级结构信息均可作为特征。问题在于应优先选取哪些特征,以及这些特征能在多大程度上决定蛋白质拟改造性能是需要进行考量的[81]。目前已经有一些蛋白质/氨基酸特征工具箱可供参考,包括AAIndex[82]、ProFET[83]等。一旦特征提取之后,将交付机器学习算法进行学习并生成可以描述数据模型的目标函数,并对蛋白质序列进行虚拟进化,通过训练和测试评估效能,最终给出预测结果(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 机器学习指导的蛋白质设计改造流程 Fig. 3 The workflow of Machine learning guided protein engineering. Green arrows depict the collection of protein mutagenesis data; orange arrows show the feature selection and learning; grey arrows display rational design guided by the trained model. |

| |

作为人工智能领域常用技术,机器学习基于大量的数据进行训练,通过各种算法解析数据并从中学习,然后对处理任务作出决策。机器学习包括3种:1)有监督学习(Supervised learning),向计算机提供原始数据及其所对应的结果(或称标签,labels),最终计算机给出定性(分类,classification)或定量(回归,regression)的预测;2)无监督学习(Unsupervised learning),只给计算机训练数据而不提供结果,最终得到聚类(Clustering)的学习结果;3)半监督学习(Semi-supervised learning),其训练数据一部分是有对应的结果,另一部分则无结果。由于蛋白质设计改造过程中可产出大量的突变体实验数据,因此有监督学习应用在该领域最为普遍[81]。

目前尚未有任何一种普适的学习算法,可以应对所有的学习任务,在蛋白质设计改造领域亦是如此。因此,科研工作者需要在相应的情况下,通过测试比对等方式选用合适的算法进行设计[84]。常见算法包括线性模型(Linear models)、随机森林(Random forests)、支持向量机(Support vector machines)、高斯过程(Gaussian processes)等。以Frances H. Arnold团队近期改造一氧化氮双加氧酶(NOD)立体选择性的工作为例,先后通过K最近邻、线性模型、决策树、随机森林等多个算法构建NOD的立体选择性催化模型,将76% (S)-ee初始突变体提升至93% (S)-ee及反转至79% (R)-ee[85]。此外,表 2列举了近十几年来机器学习指导蛋白质设计的应用实例,涉及蛋白质的热稳定性、催化活性、对映体选择性、光敏性及可溶性等多个方面。从中不难看出,机器学习的可应用性非常强,各常用算法均可覆盖某些蛋白质性能的改造。

| Algorithms | Proteins | Properties | Reference |

| Linear models | Halohydrin dehydrogenase | Volumetric productivity | [86-87] |

| Proteinase K | Activity, heat tolerance | [88] | |

| Glutathione transferase | Catalytic activity | [89-90] | |

| Random forests | Staphylococcal nuclease (Snase) | Protein thermostability | [91] |

| Support vector machines | Prion protein and transthyretin | Thermostability | [92] |

| Cytochrome P450 | Thermostability | [93] | |

| An epoxide hydrolase (AnEH) | Enantioselectivity | [94] | |

| Integral membrane proteins (IMP) that expresses in E. coli | Improving membrane protein expression | [95] | |

| Gaussian processes | Tumour suppressor protein p53 | Thermostability | [96] |

| Cytochrome P450 | Thermostability | [97] | |

| Green fluorescent protein | Fluorescence | [98] | |

| Channelrhodopsins | Expression and localization | [99] | |

| Channelrhodopsins | Light sensitivity | [100] | |

| Artificial neural networks | RNA-binding proteins | RNA binding sites/preference | [101] |

| DNA-/RNA-binding proteins | Sequence specificities | [102] | |

| DNA-binding proteins | Sequence specificities | [103] | |

| Major histocompatibility complex | Binding affinity prediction (using CNN models) | [104] | |

| More than 7 000 proteins | Ligand-binding sites prediction | [105] | |

| Major histocompatibility complex | Binding affinity prediction (using RNN models) | [106] | |

| Thousands of proteins | Protein solubility prediction | [107] | |

| 10 paires of mesophilic and thermophilic proteins | Protein stability | [108] | |

| Proteins in the latest UniProt releases | Protein subcellular localization | [109] | |

| Thousands of proteins | Secondary structure prediction | [110] | |

| 698 UniProt families and 983 Gene Ontology classes | Protein family/function prediction | [111] | |

| 11 transmembrane proteins | 3D structure prediction | [112] |

除了上述传统机器学习方法,自2006年以来,深度学习(Deep learning)成为机器学习中的一个新兴领域,如2018年DeepMind团队开发的AlphaFold在Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP)全球竞赛中获胜,总计43个蛋白质结构的预测结果中,有25个获得了最高分数。

深度学习通过训练深度神经网络,学习由低到高的特征层次,进而对输入数据进行分层抽象处理,原始特征数据能够被映射成更高层次和更抽象的数据表示,能有效增强辨别能力和减轻无关因素的影响,因此深度学习深刻变革了机器学习领域[113-114]。相比之下,传统的学习技术(如支持向量机、高斯回归和人工神经网络等)则强烈依赖于人工提取的特征,由于它们明确的特征编码原理,这些方法可能会丢失隐藏在输入数据中的敏感特征。现在已有利用卷积神经网络(Convolutional neural networks, CNN)和循环神经网络(Recurrent neural network, RNN)进行蛋白质结合亲和力的预测报道[104, 106]。相信深度学习未来可以在蛋白质设计改造领域扮演更加重要的角色。

3 结论及展望自20世纪80年代以来,蛋白质工程经历了辉煌发展的30多年,两次获得诺贝尔化学奖(1993年授予Michael Smith教授及2018年授予Frances H. Arnold教授)。从定向进化、半理性设计到理性设计,每个阶段均涌现了一系列广泛应用的改造策略和技术,同时对计算技术的依赖也逐渐加深。定向进化不依赖蛋白质晶体结构及催化机制等信息,但存在筛选瓶颈;半理性设计兼顾了序列空间多样性和筛选工作量;而理性设计则可以构建自然界不存在的新酶新反应。在开展具体的蛋白质工程案例时,应充分考虑到上述因素,基于改造目的灵活选用合适的改造策略[115-116]。

如今,数据驱动的人工智能技术正在全球范围内蓬勃兴起,为蛋白质设计改造注入了新动能。蛋白质的智能化计算设计是未来发展新趋势,目前在国内外基本上都处在起步阶段。因此,这是我国在蛋白质设计改造领域比肩世界先进水平的难得机会。期待我们能够把握好这一发展机遇,处理好人工智能在蛋白质设计改造领域的应用,通过开发具有自主知识产权的蛋白质计算设计新技术,解决“卡脖子”技术难题,满足工业界绿色、节能、环保转型升级需求,共同谱写出该领域新的光辉篇章。

| [1] |

Romero PA, Arnold FH. Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2009, 10(12): 866-876. DOI:10.1038/nrm2805 |

| [2] |

Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science, 2000, 290(5494): 1151-1155. DOI:10.1126/science.290.5494.1151 |

| [3] |

Sheldon RA, Pereira PC. Biocatalysis engineering: the big picture. Chem Soc Rev, 2017, 46(10): 2678-2691. DOI:10.1039/C6CS00854B |

| [4] |

Arnold FH. Directed evolution: bringing new chemistry to life. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2018, 57(16): 4143-4148. DOI:10.1002/anie.201708408 |

| [5] |

Kan SBJ, Lewis RD, Chen K, et al. Directed evolution of cytochrome c for carbon-silicon bond formation: bringing silicon to life. Science, 2016, 354(6315): 1048-1051. DOI:10.1126/science.aah6219 |

| [6] |

Kan SBJ, Huang XY, Gumulya Y, et al. Genetically programmed chiral organoborane synthesis. Nature, 2017, 552(7683): 132-136. DOI:10.1038/nature24996 |

| [7] |

Hammer SC, Kubik G, Watkins E, et al. Anti-Markovnikov alkene oxidation by metal-oxo- mediated enzyme catalysis. Science, 2017, 358(6360): 215-218. DOI:10.1126/science.aao1482 |

| [8] |

Zhang RK, Chen K, Huang XY, et al. Enzymatic assembly of carbon-carbon bonds via iron-catalysed sp3 C-H functionalization. Nature, 2019, 565(7737): 67-72. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0808-5 |

| [9] |

Cho I, Jia ZJ, Arnold FH. Site-selective enzymatic C-H amidation for synthesis of diverse lactams. Science, 2019, 364(6440): 575-578. DOI:10.1126/science.aaw9068 |

| [10] |

Ma SK, Gruber J, Davis C, et al. A green-by-design biocatalytic process for atorvastatin intermediate. Green Chem, 2010, 12(1): 81-86. DOI:10.1039/B919115C |

| [11] |

Savile CK, Janey JM, Mundorff EC, et al. Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from ketones applied to sitagliptin manufacture. Science, 2010, 329(5989): 305-309. DOI:10.1126/science.1188934 |

| [12] |

Zhang YJ, Zhang WX, Zheng GW, et al. Identification of an ε-keto ester reductase for the efficient synthesis of an (R)-α-lipoic acid precursor. Adv Synth Catal, 2015, 357(8): 1697-1702. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201500001 |

| [13] |

Reetz MT, Bocola M, Carballeira JD, et al. Expanding the range of substrate acceptance of enzymes: combinatorial active-site saturation test. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2005, 44(27): 4192-4196. DOI:10.1002/anie.200500767 |

| [14] |

Reetz MT, Carballeira JD. Iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) for rapid directed evolution of functional enzymes. Nat Protoc, 2007, 2(4): 891-903. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2007.72 |

| [15] |

Sun ZT, Liu Q, Qu G, et al. Utility of B-factors in protein science: interpreting rigidity, flexibility, and internal motion and engineering thermostability. Chem Rev, 2019, 119(3): 1626-1665. |

| [16] |

Li AT, Ilie A, Sun ZT, et al. Whole-cell-catalyzed multiple regio- and stereoselective functionalizations in cascade reactions enabled by directed evolution. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2016, 55(39): 12026-12029. DOI:10.1002/anie.201605990 |

| [17] |

Yu D, Wang JB, Reetz MT. Exploiting designed oxidase-peroxygenase mutual benefit system for asymmetric cascade reactions. J Am Chem Soc, 2019, 141(14): 5655-5658. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b01939 |

| [18] |

Xu J, Cen YX, Singh W, et al. Stereodivergent protein engineering of a lipase to access all possible stereoisomers of chiral esters with two stereocenters. J Am Chem Soc, 2019, 141(19): 7934-7945. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b02709 |

| [19] |

Sun ZT, Lonsdale R, Ilie A, et al. Catalytic asymmetric reduction of difficult-to-reduce ketones: triple-code saturation mutagenesis of an alcohol dehydrogenase. ACS Catal, 2016, 6(3): 1598-1605. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b02752 |

| [20] |

Sun ZT, Lonsdale R, Wu L, et al. Structure-guided triple-code saturation mutagenesis: efficient tuning of the stereoselectivity of an epoxide hydrolase. ACS Catal, 2016, 6(3): 1590-1597. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b02751 |

| [21] |

Fox RJ, Davis SC, Mundorff EC, et al. Improving catalytic function by ProSAR-driven enzyme evolution. Nat Biotechnol, 2007, 25(3): 338-344. DOI:10.1038/nbt1286 |

| [22] |

Gonzalez-Perez D, Molina-Espeja P, Garcia-Ruiz E, et al. Mutagenic organized recombination process by homologous in vivo grouping (MORPHING) for directed enzyme evolution. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(3): e90919. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0090919 |

| [23] |

Qu G, Zhao J, Zheng P, et al. Recent advances in directed evolution. Chin J Biotech, 2018, 34(1): 1-11 (in Chinese). 曲戈, 赵晶, 郑平, 等. 定向进化技术的最新进展. 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(1): 1-11. |

| [24] |

Samish I. Computational protein design. New York, NY: Humana Press, 2017.

|

| [25] |

Huang PS, Boyken SE, Baker D. The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature, 2016, 537(7620): 320-327. DOI:10.1038/nature19946 |

| [26] |

Romero-Rivera A, Garcia-Borràs M, Osuna S. Computational tools for the evaluation of laboratory- engineered biocatalysts. Chem Commun, 2016, 53(2): 284-297. |

| [27] |

Cui YL, Wu B. Biological components design for engineering requirements. Bull Chin Acad Sci, 2018, 33(11): 1150-1157 (in Chinese). 崔颖璐, 吴边. 符合工程化需求的生物元件设计. 中国科学院院刊, 2018, 33(11): 1150-1157. |

| [28] |

Li RF, Wijma HJ, Song L, et al. Computational redesign of enzymes for regio- and enantioselective hydroamination. Nat Chem Biol, 2018, 14(7): 664-670. DOI:10.1038/s41589-018-0053-0 |

| [29] |

The runners-up. Science, 2016, 354(6319): 1518-1523.

|

| [30] |

Azoitei ML, Correia BE, Ban YEA, et al. Computation-guided backbone grafting of a discontinuous motif onto a protein scaffold. Science, 2011, 334(6054): 373-376. DOI:10.1126/science.1209368 |

| [31] |

Correia BE, Bates JT, Loomis RJ, et al. Proof of principle for epitope-focused vaccine design. Nature, 2014, 507(7491): 201-206. DOI:10.1038/nature12966 |

| [32] |

Fleishman SJ, Whitehead TA, Ekiert DC, et al. Computational design of proteins targeting the conserved stem region of influenza hemagglutinin. Science, 2011, 332(6031): 816-821. DOI:10.1126/science.1202617 |

| [33] |

Procko E, Berguig GY, Shen BW, et al. A computationally designed inhibitor of an Epstein-Barr viral Bcl-2 protein induces apoptosis in infected cells. Cell, 2014, 157(7): 1644-1656. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.034 |

| [34] |

Dahiyat BI, Mayo SL. De novo protein design: fully automated sequence selection. Science, 1997, 278(5335): 82-87. DOI:10.1126/science.278.5335.82 |

| [35] |

Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, et al. Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science, 2003, 302(5649): 1364-1368. DOI:10.1126/science.1089427 |

| [36] |

Leaver-Fay A, Tyka M, Lewis SM, et al. ROSETTA3: an object-oriented software suite for the simulation and design of macromolecules. Methods Enzymol, 2011, 487: 545-574. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-381270-4.00019-6 |

| [37] |

Das R, Baker D. Macromolecular modeling with rosetta. Annu Rev Biochem, 2008, 77: 363-382. DOI:10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062906.171838 |

| [38] |

Alford RF, Leaver-Fay A, Jeliazkov JR, et al. The Rosetta all-atom energy function for macromolecular modeling and design. J Chem Theory Comput, 2017, 13(6): 3031-3048. DOI:10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00125 |

| [39] |

Cui YL, Wu B. A brief overview of computational protein structure prediction and enzyme design. Guangxi Sci, 2017, 24(1): 1-6 (in Chinese). 崔颖璐, 吴边. 计算机辅助蛋白结构预测及酶的计算设计研究进展. 广西科学, 2017, 24(1): 1-6. |

| [40] |

Kiss G, Çelebi-Ölçüm N, Moretti R, et al. Computational enzyme design. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2013, 52(22): 5700-5725. DOI:10.1002/anie.201204077 |

| [41] |

Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, et al. De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes. Science, 2008, 319(5868): 1387-1391. DOI:10.1126/science.1152692 |

| [42] |

Röthlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, et al. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature, 2008, 453(7192): 190-195. DOI:10.1038/nature06879 |

| [43] |

Siegel JB, Zanghellini A, Lovick HM, et al. Computational design of an enzyme catalyst for a stereoselective bimolecular Diels-Alder reaction. Science, 2010, 329(5989): 309-313. DOI:10.1126/science.1190239 |

| [44] |

Grigoryan G, Reinke AW, Keating AE. Design of protein-interaction specificity gives selective bZIP- binding peptides. Nature, 2009, 458(7240): 859-864. DOI:10.1038/nature07885 |

| [45] |

Fry HC, Lehmann A, Saven JG, et al. Computational design and elaboration of a de novo heterotetrameric α-helical protein that selectively binds an emissive abiological (porphinato)zinc chromophore. J Am Chem Soc, 2010, 132(11): 3997-4005. DOI:10.1021/ja907407m |

| [46] |

Korendovych IV, Senes A, Kim YH, et al. De novo design and molecular assembly of a transmembrane diporphyrin-binding protein complex. J Am Chem Soc, 2010, 132(44): 15516-15518. DOI:10.1021/ja107487b |

| [47] |

Grigoryan G, Kim YH, Acharya R, et al. Computational design of virus-like protein assemblies on carbon nanotube surfaces. Science, 2011, 332(6033): 1071-1076. DOI:10.1126/science.1198841 |

| [48] |

Karanicolas J, Corn JE, Chen I, et al. A de novo protein binding pair by computational design and directed evolution. Mol Cell, 2011, 42(2): 250-260. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.010 |

| [49] |

Fry HC, Lehmann A, Sinks LE, et al. Computational de novo design and characterization of a protein that selectively binds a highly hyperpolarizable abiological chromophore. J Am Chem Soc, 2013, 135(37): 13914-13926. DOI:10.1021/ja4067404 |

| [50] |

Tinberg CE, Khare SD, Dou JY, et al. Computational design of ligand-binding proteins with high affinity and selectivity. Nature, 2013, 501(7466): 212-216. DOI:10.1038/nature12443 |

| [51] |

Huang PS, Oberdorfer G, Xu CF, et al. High thermodynamic stability of parametrically designed helical bundles. Science, 2014, 346(6208): 481-485. DOI:10.1126/science.1257481 |

| [52] |

Thomson AR, Wood CW, Burton AJ, et al. Computational design of water-soluble α-helical barrels. Science, 2014, 346(6208): 485-488. DOI:10.1126/science.1257452 |

| [53] |

Joh NH, Wang T, Bhate MP, et al. De novo design of a transmembrane Zn2+-transporting four-helix bundle. Science, 2014, 346(6216): 1520-1524. DOI:10.1126/science.1261172 |

| [54] |

Wang RY, Kudryashev M, Li XM, et al. De novo protein structure determination from near-atomic- resolution cryo-EM maps. Nat Methods, 2015, 12(4): 335-338. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.3287 |

| [55] |

Lin YR, Koga N, Tatsumi-Koga R, et al. Control over overall shape and size in de novo designed proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(40): E5478-E5485. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1509508112 |

| [56] |

Huang PS, Feldmeier K, Parmeggiani F, et al. De novo design of a four-fold symmetric TIM-barrel protein with atomic-level accuracy. Nat Chem Biol, 2016, 12(1): 29-34. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.1966 |

| [57] |

Boyken SE, Chen ZB, Groves B, et al. De novo design of protein homo-oligomers with modular hydrogen- bond network-mediated specificity. Science, 2016, 352(6286): 680-687. DOI:10.1126/science.aad8865 |

| [58] |

Bhardwaj G, Mulligan VK, Bahl CD, et al. Accurate de novo design of hyperstable constrained peptides. Nature, 2016, 538(7625): 329-335. DOI:10.1038/nature19791 |

| [59] |

Dang BB, Wu HF, Mulligan VK, et al. De novo design of covalently constrained mesosize protein scaffolds with unique tertiary structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2017, 114(41): 10852-10857. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1710695114 |

| [60] |

Polizzi NF, Wu YB, Lemmin T, et al. De novo design of a hyperstable non-natural protein-ligand complex with sub-Å accuracy. Nat Chem, 2017, 9(12): 1157-1164. DOI:10.1038/nchem.2846 |

| [61] |

Chevalier A, Silva DA, Rocklin GJ, et al. Massively parallel de novo protein design for targeted therapeutics. Nature, 2017, 550(7674): 74-79. DOI:10.1038/nature23912 |

| [62] |

Geiger-Schuller K, Sforza K, Yuhas M, et al. Extreme stability in de novo-designed repeat arrays is determined by unusually stable short-range interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2018, 115(29): 7539-7544. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1800283115 |

| [63] |

Dou JY, Vorobieva AA, Sheffler W, et al. De novo design of a fluorescence-activating β-barrel. Nature, 2018, 561(7724): 485-491. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0509-0 |

| [64] |

Marcos E, Chidyausiku TM, McShan AC, et al. De novo design of a non-local β-sheet protein with high stability and accuracy. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2018, 25(11): 1028-1034. DOI:10.1038/s41594-018-0141-6 |

| [65] |

Shen H, Fallas JA, Lynch E, et al. De novo design of self-assembling helical protein filaments. Science, 2018, 362(6415): 705-709. DOI:10.1126/science.aau3775 |

| [66] |

Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, et al. De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15. Nature, 2019, 565(7738): 186-191. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7 |

| [67] |

Xiong P, Wang M, Zhou XQ, et al. Protein design with a comprehensive statistical energy function and boosted by experimental selection for foldability. Nat Commun, 2014, 5: 5330. DOI:10.1038/ncomms6330 |

| [68] |

Zhou XQ, Xiong P, Wang M, et al. Proteins of well-defined structures can be designed without backbone readjustment by a statistical model. J Struct Biol, 2016, 196(3): 350-357. DOI:10.1016/j.jsb.2016.08.002 |

| [69] |

Liu HY, Chen Q. Computational protein design for given backbone: recent progresses in general method-related aspects. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2016, 39: 89-95. DOI:10.1016/j.sbi.2016.06.013 |

| [70] |

Chu HY, Liu HY. TetraBASE: a side chain- independent statistical energy for designing realistically packed protein backbones. J Chem Inf Model, 2018, 58(2): 430-442. DOI:10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00677 |

| [71] |

Murphy PM, Bolduc JM, Gallaher JL, et al. Alteration of enzyme specificity by computational loop remodeling and design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2009, 106(23): 9215-9220. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0811070106 |

| [72] |

Siegel JB, Smith AL, Poust S, et al. Computational protein design enables a novel one-carbon assimilation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(12): 3704-3709. |

| [73] |

Wijma HJ, Floor RJ, Jekel PA, et al. Computationally designed libraries for rapid enzyme stabilization. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2014, 27(2): 49-58. DOI:10.1093/protein/gzt061 |

| [74] |

Wijma HJ, Fürst MJLJ, Janssen DB. A computational library design protocol for rapid improvement of protein stability: FRESCO//Bornscheuer UT, Höhne M, Eds. Protein Engineering. New York, NY: Humana Press, 2018: 69-85.

|

| [75] |

Arabnejad H, Dal Lago M, Jekel PA, et al. A robust cosolvent-compatible halohydrin dehalogenase by computational library design. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2017, 30(3): 175-189. |

| [76] |

Floor RJ, Wijma HJ, Colpa DI, et al. Computational library design for increasing haloalkane dehalogenase stability. ChemBioChem, 2014, 15(11): 1660-1672. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201402128 |

| [77] |

Bu YF, Cui YL, Peng Y, et al. Engineering improved thermostability of the GH11 xylanase from Neocallimastix patriciarum via computational library design. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 102(8): 3675-3685. DOI:10.1007/s00253-018-8872-1 |

| [78] |

Jordan MI, Mitchell TM. Machine learning: trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science, 2015, 349(6245): 255-260. DOI:10.1126/science.aaa8415 |

| [79] |

Yang KK, Wu Z, Arnold FH. Machine- learning-guided directed evolution for protein engineering. Nat Methods, 2019, 16(8): 687-694. DOI:10.1038/s41592-019-0496-6 |

| [80] |

Li GY, Dong YJ, Reetz MT. Can machine learning revolutionize directed evolution of selective enzymes?. Adv Synth Catal, 2019, 361(11): 2377-2386. |

| [81] |

Zhou XX, Wang YB, Pan YJ, et al. Differences in amino acids composition and coupling patterns between mesophilic and thermophilic proteins. Amino Acids, 2008, 34(1): 25-33. |

| [82] |

Kawashima S, Pokarowski P, Pokarowska M, et al. AAindex: amino acid index database, progress report 2008. Nucleic Acids Res, 2008, 36(S1): D202-D205. |

| [83] |

Ofer D, Linial M. ProFET: feature engineering captures high-level protein functions. Bioinformatics, 2015, 31(21): 3429-3436. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv345 |

| [84] |

Wolpert DH. The lack of A priori distinctions between learning algorithms. Neural Comput, 1996, 8(7): 1341-1390. DOI:10.1162/neco.1996.8.7.1341 |

| [85] |

Wu Z, Kan SBJ, Lewis RD, et al. Machine learning-assisted directed protein evolution with combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2019, 116(18): 8852-8858. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1901979116 |

| [86] |

Fox R. Directed molecular evolution by machine learning and the influence of nonlinear interactions. J Theor Biol, 2005, 234(2): 187-199. DOI:10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.11.031 |

| [87] |

Fox R, Roy A, Govindarajan S, et al. Optimizing the search algorithm for protein engineering by directed evolution. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2003, 16(8): 589-597. DOI:10.1093/protein/gzg077 |

| [88] |

Liao J, Warmuth MK, Govindarajan S, et al. Engineering proteinase K using machine learning and synthetic genes. BMC Biotechnol, 2007, 7: 16. DOI:10.1186/1472-6750-7-16 |

| [89] |

Govindarajan S, Mannervik B, Silverman JA, et al. Mapping of amino acid substitutions conferring herbicide resistance in wheat glutathione transferase. ACS Synth Biol, 2015, 4(3): 221-227. |

| [90] |

Musdal Y, Govindarajan S, Mannervik B. Exploring sequence-function space of a poplar glutathione transferase using designed information-rich gene variants. Protein Eng Des Sel, 2017, 30(8): 543-549. DOI:10.1093/protein/gzx045 |

| [91] |

Li YQ, Fang JW. PROTS-RF: a robust model for predicting mutation-induced protein stability changes. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(10): e47247. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0047247 |

| [92] |

Capriotti E, Fariselli P, Calabrese R, et al. Predicting protein stability changes from sequences using support vector machines. Bioinformatics, 2005, 21(S2): ii54-ii58. |

| [93] |

Buske FA, Their R, Gillam EMJ, et al. In silico characterization of protein chimeras: relating sequence and function within the same fold. Proteins, 2009, 77(1): 111-120. |

| [94] |

Zaugg J, Gumulya Y, Malde AK, et al. Learning epistatic interactions from sequence-activity data to predict enantioselectivity. J Comput Aided Mol Des, 2017, 31(12): 1085-1096. DOI:10.1007/s10822-017-0090-x |

| [95] |

Saladi SM, Javed N, Müller A, et al. A statistical model for improved membrane protein expression using sequence-derived features. J Biol Chem, 2018, 293(13): 4913-4927. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA117.001052 |

| [96] |

Pires DEV, Ascher DB, Blundell TL. mCSM: predicting the effects of mutations in proteins using graph-based signatures. Bioinformatics, 2014, 30(3): 335-342. |

| [97] |

Romero PA, Krause A, Arnold FH. Navigating the protein fitness landscape with Gaussian processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(3): E193-E201. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1215251110 |

| [98] |

Saito Y, Oikawa M, Nakazawa H, et al. Machine-learning-guided mutagenesis for directed evolution of fluorescent proteins. ACS Synth Biol, 2018, 7(9): 2014-2022. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.8b00155 |

| [99] |

Bedbrook CN, Yang KK, Rice AJ, et al. Machine learning to design integral membrane channelrhodopsins for efficient eukaryotic expression and plasma membrane localization. PLoS Comput Biol, 2017, 13(10): e1005786. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005786 |

| [100] |

Bedbrook CN, Yang KK, Robinson JE, et al. Machine learning-guided channelrhodopsin engineering enables minimally-invasive optogenetics. bioRxiv, 2019. DOI:10.1101/565606 |

| [101] |

Zhang S, Zhou JT, Hu HL, et al. A deep learning framework for modeling structural features of RNA-binding protein targets. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016, 44(4): e32. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv1025 |

| [102] |

Alipanahi B, Delong A, Weirauch MT, et al. Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33(8): 831-838. DOI:10.1038/nbt.3300 |

| [103] |

Zeng HY, Edwards MD, Liu G, et al. Convolutional neural network architectures for predicting DNA-protein binding. Bioinformatics, 2016, 32(12): i121-i127. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btw255 |

| [104] |

Hu JJ, Liu ZH. DeepMHC: deep convolutional neural networks for high-performance peptide-mhc binding affinity prediction. bioRxiv, 2017. DOI:10.1101/239236 |

| [105] |

Jiménez J, Doerr S, Martínez-Rosell G, et al. DeepSite: protein-binding site predictor using 3D-convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics, 2017, 33(19): 3036-3042. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btx350 |

| [106] |

Mazzaferro C. Predicting protein binding affinity with word embeddings and recurrent neural networks. bioRxiv, 2017. DOI:10.1101/128223 |

| [107] |

Khurana S, Rawi R, Kunji K, et al. DeepSol: a deep learning framework for sequence-based protein solubility prediction. Bioinformatics, 2018, 34(15): 2605-2613. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty166 |

| [108] |

Giollo M, Martin AJ, Walsh I, et al. NeEMO: a method using residue interaction networks to improve prediction of protein stability upon mutation. BMC Genomics, 2014, 15(S4): S7. |

| [109] |

Almagro Armenteros JJ, Sønderby CK, Sønderby SK, et al. DeepLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics, 2017, 33(21): 3387-3395. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btx431 |

| [110] |

Sønderby SK, Winther O. Protein secondary structure prediction with long short term memory networks. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1412.7828, 2014.

|

| [111] |

Szalkai B, Grolmusz V. Near perfect protein multi-label classification with deep neural networks. Methods, 2018, 132: 50-56. DOI:10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.06.034 |

| [112] |

Hopf TA, Colwell LJ, Sheridan R, et al. Three-dimensional structures of membrane proteins from genomic sequencing. Cell, 2012, 149(7): 1607-1621. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.012 |

| [113] |

Bengio Y. Learning deep architectures for AI. Found Trends Mach Learn, 2009, 2(1): 1-127. DOI:10.1561/2200000006 |

| [114] |

LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature, 2015, 521(7553): 436-444. DOI:10.1038/nature14539 |

| [115] |

Qu G, Li AT, Acevedo-Rocha CG, et al. The crucial role of methodology development in directed evolution of selective enzymes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2019, 58. DOI:10.1002/anie.201901491 |

| [116] |

Qu G, Zhang K, Jiang YY, et al. The Nobel Prize in chemistry 2018: the directed evolution of enzymes and the phage display technologies. J Biol, 2019, 36(1): 1-6 (in Chinese). 曲戈, 张锟, 蒋迎迎, 等. 2018诺贝尔化学奖:酶定向进化与噬菌体展示技术. 生物学杂志, 2019, 36(1): 1-6. |

2019, Vol. 35

2019, Vol. 35