中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 池淏甜, 陈实

- Chi Haotian, Chen Shi

- 基因组学技术解码天然产物合成

- Genomics approaches decode natural products synthesis

- 生物工程学报, 2019, 35(10): 1889-1900

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2019, 35(10): 1889-1900

- 10.13345/j.cjb.190219

-

文章历史

- Received: March 18, 2019

- Accepted: July 29, 2019

20世纪40年代,第一个抗生素青霉素被发现并成功运用于临床以后,已有数千种结构多样的天然产物被发现并广泛应用于人类的生产生活中[1]。天然产物已成为抗生素、免疫抑制剂、抗恶性细胞增生剂、抗高血压和抗病毒等药物的重要来源[2-3]。在过去的35年中,美国FDA批准的药物超过半数都是源于天然产物[4]。因此,挖掘生物中的天然产物是制药产业的重要支柱之一。

传统观点认为生物只能产生数量有限的次级代谢产物。但随着DNA测序技术和生物信息学的快速发展,链霉菌和曲霉属真菌的第一个基因组序列被公布[5-6],生物潜藏的天然产物合成能力被发现。生物信息学分析预测链霉菌基因组,发现其可以产生约150 000多种潜在的抗菌药物[7-8],然而到2005年只有约7 600个天然产物被确认[4]。在标准的实验室生长条件下,多数次级代谢产物都未能表达或是低表达。这些“沉默”的生物合成基因簇(Biosynthetic gene clusters,BGCs)可能编码众多结构新颖的生物活性分子,而这些天然产物可以广泛用于医药或是畜牧业[9]。因此,挖掘并唤醒这些“沉默”的次级代谢途径可以极大地丰富现有的天然产物库,为研发更具临床应用价值的药物,解决愈发严重的抗生素耐药性问题提供来源[10]。

组学时代的来临,基因组学、转录组学、蛋白组学和代谢组学等学科研究的不断深入,有利于挖掘并激活生物中“沉默”的天然产物合成途径。本文将从天然产物合成基因簇的挖掘、“沉默”天然产物合成途径激活和生物底盘构建3个方面介绍组学技术在天然产物挖掘中的研究进展。

1 天然产物合成基因簇的挖掘16S核糖体RNA (Ribosomal RNA,rRNA)的分析数据显示,只有1%的细菌可以在实验室条件下进行培养[11]。因此为了获得活性丰富的天然产物,就需要突破传统基于生物活性寻找天然产物的方法,寻找新的方法。宏基因组学则直接从环境DNA (Environment DNA,eDNA)中获取隐藏的编码天然产物的基因序列[12]。基于快速便捷的测序技术和累积的丰富数据信息,这种新方法可以打破传统筛选模式,挖掘更多结构多样、生物活性优良的天然产物。

1.1 宏基因组学宏基因组学的挖掘工作流程主要分为两种。传统方法需要构建巨大的cosmid文库,并对单个eDNA克隆进行功能筛选。筛选克隆的方法较为多样,如可视的检测信号、生物活性、报告/生物传感器或特定的催化反应。最新发展的方法是基于生物合成中保守DNA序列的相似性,选择性地获取环境样本中潜在的生物合成基因簇。随后将筛选得到的基因簇进行异源表达,最终获得新的化合物[13]。

传统方法中,宏基因组文库是通过提取eDNA、克隆并连接到穿梭载体上,然后转化到合适的异源宿主中而构建得到的。筛选阳性克隆的主要方法是观察表型或色谱分离鉴定,也可以用报告/生物传感器筛选系统,如代谢调节表达系统(Metabolite-regulated expression,METREX)[14]和基质诱导基因表达筛选系统(Substrate-induced gene expression screening,SIGEX)[15]。然而,这种方法发现的天然产物较少,结构相对比较简单,如抗菌色素(Violacein)[16]、靛玉红(Indirubin)及其同分异构体(Indigo)[17]、N-酰基酪氨酸[18]等。

最新发展的方法是从环境样品中提取粗eDNA,通过聚合酶链反应(Polymerase chain reaction,PCR)扩增子特异地针对天然产物生物合成基因簇内的序列进行筛选。其中PCR扩增子的混合物称为天然产物序列标签(Natural product sequence tags,NPSTs)。基于NPSTs的系统发育关系预测工具,如天然产物多样性预测工具(Environmental surveyor of natural product,eSNaPD)[19]和天然产物结构域检测工具(Natural product domain search,NaPDos)[20],可以对DNA序列标签进行系统分类和生物合成来源评价,并与数据库进行比较,重组潜在的目标生物合成基因簇。新方法构建的宏基因组文库是由重组的生物合成基因簇所组成,可以排除大多数与生物合成途径无关的DNA序列。蛋白酶体抑制剂landepoxin A是通过该方法筛选得到,它是通过比较酮合成酶(Ketosynthase,KS)结构域序列标签和已知的环氧酮生物合成基因簇的KS结构域,从宏基因组样本中识别环氧酮蛋白酶抑制剂的衍生物而发现[21]。Brady等通过该方法筛选到色氨酸二聚体hydroxysporine和reductasporine[22]、细胞毒性蒽环霉素arimetamycin A[23]、抗生素tetarimycin A[24]、malacidins A和B[25]、蛋白酶体抑制剂clarepoxcins A-E、landepoxcins A和B[21]。

1.2 生物信息学自20世纪末对生物体进行基因组分析以来,已有超过7 000个微生物的基因组信息被报道。在这之前,人们认为产生次级代谢物的微生物只含有少数几种BGCs。然而,阿维链霉菌和天蓝链霉菌的基因组解码后发现有20–37个未知的生物合成基因簇[6, 26-27]。生物信息学分析显示天然产物生物合成基因簇超过总基因组的5%–7%[28]。丝状真菌构巢曲霉Aspergillus nidulans的基因组具有更大的潜力,推测有56条次级代谢途径[29]。此外,分析不同生态位的生物群落,如人类微生物群[30]和环境样本[31],进一步揭示了天然产物的多样性。

随着新一代测序技术的应用,DNA序列分析的处理速度和准确性显著提高,成本大幅度降低。获得的大量基因组分析数据让公共数据库很好地建立起来,利用BLAST和FASTA可以在一定程度上推断出未知基因的功能[32-33]。目前,除了利用同源性预测功能外,隐马尔可夫模型(Hidden Markov model,HMM)分析蛋白质家族(Protein family,Pfam)被广泛应用[34]。专门分析预测BGCs产物的统计模型antiSMASH也被公开[35]。由于计算机处理能力的显著提高,蛋白质功能预测的精确度也有所提升,BGCs的评估更加精准[36]。因此,从基因组序列数据中挖掘次级代谢生物合成基因簇的方法被广泛应用。

分析基因组中可能存在的次级代谢生物合成酶的编码基因是挖掘新型天然产物的经典方法。虽然次级代谢物结构丰富多样,但其生物合成机理是相对保守的,尤其是核心酶的氨基酸序列相似度非常高[37]。经典挖掘方法运用了反向遗传学原理,即以一个或多个“参考”酶的基因序列来确定目标生物基因组序列中的同源基因。常用软件有BLAST[38]、DIAMOND[39]、HMMer[40]和antiSMASH,其中antiSMASH的3.04版本可以识别44种不同的基因簇类型[35, 41-42]。经典挖掘方法找到的生物合成基因簇通常都是较容易识别的,如泰斯巴汀(Teixobactin)[43]、卷曲霉素(Cypemycin)[44]、瑞斯托霉素(Ristomycin)[45]等。

最新发展的方法不再专注于参与合成的单一基因,而是通过分析部分或全部基因簇、抗性或调控基因来深入挖掘新型天然产物。Cimermancic等运用双态HMM建立了一个寻找BGCs的算法[46]。首先用677个已验证的次级代谢生物合成基因簇和随机选取的非次级代谢生物合成基因序列中的Pfam域字符串验证该模型。然后用该概率模型对1 154个原核生物基因组进行筛选,得到33 000个可能的BGCs,其中有10 700个BGCs的评分很高[46]。这些分析数据表明挖掘微生物中的新型天然产物潜力巨大。

随着人们对天然产物生物合成途径的认识不断深入,发现BGCs不仅含有编码天然产物合成的生化酶,还有调控元件、转运蛋白和抗性基因等。因此,逐渐发展出基于抗性或是调控因子的天然产物挖掘方法。Wright等验证了对糖肽和安莎霉素类抗生素耐受的微生物更有可能产生类似的化合物,并开发了基于抗生素耐药性的挖掘平台用于分离特定的抗生素产生菌[47-48]。Moore等则将这种方法进一步改良优化,开发了一种靶向基因组挖掘方法[49];他们筛选了86株海洋放线菌属Salinispora的菌株,确定了一个在细菌脂肪酸合酶附近的非常规PKS-NRPS基因簇。通过克隆、异源表达和突变分析,发现该基因簇与已知的脂肪酸合成酶抑制剂硫拉霉素的生物合成有关。因此,将假定的耐药基因与“沉默”的次级代谢基因簇相关联,是一种挖掘天然产物的有效途径。

2 “沉默”天然产物合成途径的激活宏基因组学、生物信息学解析基因组序列发现的BGCs在特定生长条件下没有表达或是表达量低检测不到,这些BGCs被称为“沉默”天然产物生物合成基因簇。目前主要有两种策略可以激活这些“沉默”BGCs。一是随机激活,主要有对生长条件的经验优化[50]、添加化学诱变剂[51-52]、微量金属离子[53]、提供外源性小分子[54]、核糖体工程[55-57]、与其他生物共培养等方法。二是基于基因组序列的靶向激活[58],主要针对调节基因[59]。

2.1 随机激活随机激活通过高通量筛选获得目的菌株。改变菌株的生长环境,如温度、pH、共培养或添加化学诱导剂等,均可诱导BGCs表达[50-51, 53-54]。在Streptomyces spp.培养基中加入低浓度稀土元素如钪和镧,不仅提高了已知抗生素的产量同时诱导了新型天然产物的产生[60-61]。2016年,筛选含有30 569个小分子的化合物库,发现了19个新的化学诱变剂[62]。这些诱变剂能够使天蓝色链霉菌菌落的色素沉着,而色素的产生又通常与天然产物的生成有关。其中ARC2被认为是一种极具潜力的化学诱变剂,其衍生物Cl-ARC用于筛选50株不同的放线菌,有至少23%的BGCs被激活,还有3种罕见的对细菌和真核生物具有活性的天然产物[62-63]。烟曲霉菌Aspergillus fumigatus与链霉菌Streptomyces rapamycinicus进行共培养激活了烟曲霉菌中一个聚酮类BGC的表达,发现了一种新型多酚类天然产物并命名为烟环烷(Fumicyclines)[64]。这类化合物对S. rapamycinicus的生长有一定抑制作用,并可以在防御真菌时发挥作用。

变铅青链霉菌Streptomyces lividans中S12的突变激活抗生素actinorhodin的生物合成途径,而该BGC在变铅青链霉菌中通常是沉默的[65]。进一步研究发现编码RNA聚合酶(RNA polymerase,RNAP)、30S核糖体蛋白S12和其他核糖体蛋白的基因突变可以上调特定BGCs的转录和翻译。鸟苷四磷酸(Guanosine tetraphosphate,ppGpp)是细菌适应环境压力非常重要的信号素,也可以诱导抗生素的生物合成[66]。S12是细菌核糖体小亚单位的组成部分,参与翻译起始并决定翻译的准确性。ppGpp可以与RNAP结合,参与控制rRNA的生物合成同时调节RNAP在不同启动子上启动转录的能力[67]。因此怀疑RNAP的突变可以使其模仿与ppGpp结合的构象,由此激活沉默BGCs的转录[68-69]。有研究使用作用于核糖体的抗生素链霉素和庆大霉素以及作用于RNAP的抗生素利福平分别对不同的放线菌进行筛选,使编码S12的基因rpsL和编码RNAP的β-亚基的基因rpoB自发突变。最后发现中杀菌素链霉菌Streptomyces mauvecolor的突变株产生了8个抗菌天然产物,随后的结构研究显示这是一种新型抗生素piperidamycins[55]。假单胞菌、芽孢杆菌、分支杆菌等微生物的核糖体突变都可以激活生物合成基因簇[61, 65]。此外,全局调控因子的改变也会诱导某些“沉默”BGCs的表达。如将天蓝色链霉菌中多效调控基因absA1的等位基因导入到异源链霉菌Streptomyces flavopersicus中,诱导S. flavopersicus产生了具有广谱抗菌活性的pulvomycin[70]。

2.2 靶向激靶向激活相较于随机激活具有更好的可控性和可预测性。该方法需要设计和实施特定的策略来激活目标BGCs,通量低于随机激活。已知天然产物生物合成基因簇内或附近编码转录调控因子的基因会影响天然产物的表达[58-59, 71]。因此,诱导激活因子的表达或敲除编码抑制因子的基因都是非常有效的激活“沉默”BGCs的方法。

在产二素链霉菌Streptomyces ambofaciens基因组中发现一个编码PKS的基因簇[72]。生物信息学分析预测该BGC的代谢产物是一种含有新型碳骨架的聚酮化合物,但qRT-PCR分析显示该基因簇在实验室生长条件下低表达。分析发现基因簇内的samR0484基因可能编码特异性转录激活因子,该因子属于LAL家族调控因子。过表达samR0484可诱导该PKS和其他生物合成基因的表达,发现了一类新型的大环内酯类抗生素stambomycins[72]。TetR家族抑制蛋白含有一个螺旋的DNA结合结构域和一个响应小分子配体的受体结构域。在特定的响应配体缺失时,TetR二聚体会与DNA结合阻止下游基因的转录[73]。失活TetR家族抑制蛋白可以激活多杰霉素(Jadomycin)[74-75]、卡那霉素(Kinamycin)[76]、aurici[77]、ceoelimycin[78]和gaburedins[79]等多种天然产物的表达。

目前使用天然启动子、修饰启动子和合成启动子来挖掘天然产物是非常有效的靶向激活方法[58]。启动子可能是激活“沉默”BGCs和提高天然产物产量所必需的。因此有研究小组不断丰富启动子库[80]。他们已经成功合成了56个启动子,将其分为强、中、弱3种不同强度的启动子,并验证在多个放线菌菌株中均有活性[81]。这种合成启动子库为未来更好地靶向激活生物合成途径提供了更多选择。

3 生物底盘构建多数生物在实验室生长条件下较难培养,遗传背景复杂且不易进行基因操作,其他代谢途径也会影响目标BGC的表达。因此,构建具有精简化基因组的生物底盘,对于挖掘天然产物至关重要[82]。目前构建生物底盘主要有“自上而下”和“自下而上”两种策略。

3.1 “自上而下”构建策略基于对基因组认识的不断深入,“自上而下”主要是去除赘余基因,降低非必要代谢途径和复杂调控网络的干扰。优化细胞代谢途径提高对底物和能量的利用率,增加底盘的可预测性和可控性[83]。

“自上而下”的构建思路主要是通过比较分析来自不同生物的基因组,并结合已有的实验数据,分析出非必需基因[84]。然后,使用质粒和线性DNA介导、位点特异性重组酶、转座子和CRISPR/Cas系统等方法进行缺失,构建基因组精简的底盘。目前,在大肠杆菌[85-89]、链霉菌[82, 90-92]、枯草芽孢杆菌[93-95]和假单胞菌[96-98]等生物中开展了底盘构建工作。以阿维链霉菌SUKA17为例,研究者使用Cre-loxP重组系统对阿维链霉菌基因组进行分步缺失,去除了约20%的基因组,消除了67%的IS序列和78%的转座基因。此外,SUKA17也是首个用于异源表达次级代谢生物合成途径的放线菌底盘[92]。SUKA17基因组的稳定性增加且可以在基础培养基中正常生长,不产阿维链霉菌内源次级代谢物如阿维霉素、寡霉素、菲律宾菌素和萜类化合物等。目前,已有超过30多种不同的生物合成基因簇在SUKA17中进行表达,如核苷类、多肽类、氨基糖苷类等[91, 99]。多数BGCs异源导入到底盘后可直接检测到目标代谢物,少数合成基因簇需要导入调控基因。如将75 kb含有pladienolide整个生物合成基因簇的BAC克隆插入到SUKA17中,并没有产生pladienolide。转录分析表明,pladienolide生物合成基因簇和SUKA17基因组中并没有相关的调控基因可以激活该代谢途径。在导入调控基因pldR后,突变株可以合成pladienolide。此外,SUKA17可以使经密码子优化后的合成基因有效表达,产生植物萜类合成中间前体物质。阿维链霉菌基因敲除后的底盘更适用于表达多种不同的次级代谢生物合成基因簇,可能因为精简化的底盘能为新引入的异源代谢途径提供充足的生物合成前体物[100]。这些充分说明生物底盘的基因组稳定性好且系统兼容性强,为天然产物的挖掘提供良好的基础。

3.2 “自下而上”构建策略“自下而上”构建策略则是尝试从头合成生物底盘。随着DNA合成、测序和移植技术的不断发展,使从头合成复杂且长的DNA序列成为可能[101]。该方法主要使用PCR组装具有同源序列的短片段,最终构建得到全合成生物底盘[102-103]。

2004年,使用PCR技术成功合成了一个长32 kb的聚酮合酶基因簇[103]。虽然合成价格昂贵且错误率高,但这一成果使制备人工细胞成为可能。2008年,Venter等合成了第一个完整的生物体基因组尿道支原体M. genitalium JCVI-1.0[101]。该全合成基因组长582 970 bp,所含基因与野生型尿道支原体M. genitalium G37几乎完全相同[104]。构建流程为化学合成101个5–7 kb具有重叠序列的片段,并通过测序进行了验证。然后,通过体外重组得到约24 kb、72 kb (1/8基因组)和144 kb (1/4基因组)的中间片段。最后在酿酒酵母中组装得到完整的基因组。

计算机设计好基因组序列,通过合成、组装得到1.08 Mb的丝状支原体基因组JCVI- syn1.0[104-105]。将其移植到山羊支原体受体细胞中,产生仅受该合成染色体控制的丝状支原体细胞。JCVI-syn1.0的组装是通过体外酶策略和酵母体内重组相结合完成的。JCVI-syn1.0具有预期的表型特征,能够持续自我复制。随后基于syn1.0基因组,设计并构建了531 kb的基因组JCVIsyn3.0,该基因组含有473个基因,编码438个蛋白和35个带注释的RNA[106]。合成基因组JCVIsyn3.0比任何已知的可以在无菌培养中生长的生物体的基因组都要小。首先,利用Tn5诱变技术来识别必要基因、准必要基因和非必要基因。随后,验证准必要基因。最后,通过设计、合成和测试,构建得到最小基因组JCVIsyn3.0。JCVIsyn3.0是一个多功能底盘,可以用于研究生命的核心功能和探索全基因组。这样将为未来天然产物的挖掘提供更多可能。

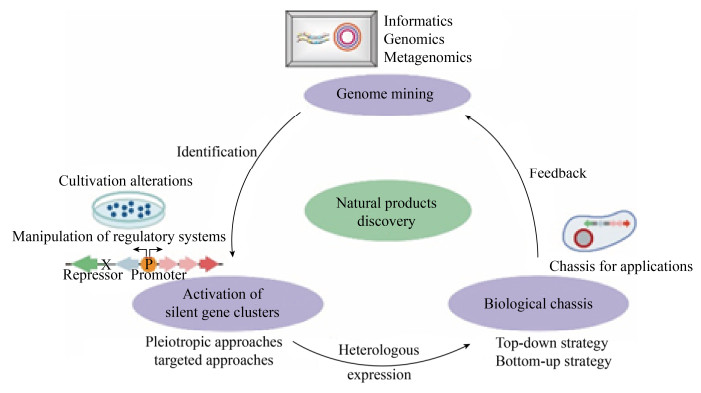

4 展望20世纪末,生物基因组测序的实现让我们了解到基因组中天然产物生物合成基因簇比预想的多。实质上只有很小部分的天然产物被开发,多数在实验室生长条件下是保持“沉默”的。随着生物信息学、基因测序、分子遗传学等学科的快速发展,天然产物合成基因簇的挖掘、代谢途径的激活和生物底盘的构建在天然产物挖掘中得到了广泛应用。我们可以综合使用各种策略高效地挖掘并唤醒生物中“沉默”的生物合成基因簇(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 基因组学技术解析天然产物合成的流程 Fig. 1 Schematic illustration of natural products synthesis using genomics approaches. |

| |

天然产物合成基因簇的挖掘中,宏基因组学揭示了未经培养的生物可以产生结构复杂并具有生物活性的天然产物,证明eDNA是一个丰富资源。然而宏基因组学仍需要突破两个局限性问题,一是如何从土壤样本中分离得到宏基因组学的DNA样本库。因为收集含有新型生物合成途径的eDNA需要花费大量时间,并且需要懂得基础的生态学知识。二是如何将宏基因组文库中的BGCs进行异源表达。多数BGCs在异源宿主中是沉默的,可能是受密码子、稀有tRNAs、毒性或稳定性等因素的影响。在挖掘到可能的天然产物生物合成途径后,需要随机激活或靶向激活“沉默”基因簇的表达。通常随机激活不需要预先了解BGC的机理,且可以进行高通量的筛选,但对激活结果却无法预估。靶向激活则需要预先对通路有所了解,其通量较低但是具有可控性和可预测性。此外,生物底盘的构建无论对于基因组挖掘还是激活“沉默”基因簇的表达都非常重要。目前有“自上而下”和“自下而上”两种策略。其中“自上而下”是通过去除赘余基因得到精简化的生物底盘。“自下而上”则是从头合成基因组。天然产物挖掘工作充满挑战,但随着组学技术的不断发展,将会有更多具有新型结构的天然产物被发现并广泛用于人们的生产生活中。

| [1] |

Jones D, Metzger HJ, Schatz A, et al. Control of gram-negative bacteria in experimental animals by Streptomycin. Science, 1944, 100(2588): 103-105. DOI:10.1126/science.100.2588.103 |

| [2] |

Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep, 2001, 18(4): 380-416. DOI:10.1039/a909079g |

| [3] |

Meier JL, Burkart MD. Proteomic analysis of polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 2011, 15(1): 48-56. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.021 |

| [4] |

Bérdy J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2005, 58(1): 1-26. |

| [5] |

Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, et al. Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae. Nature, 2005, 438(7071): 1157-1161. DOI:10.1038/nature04300 |

| [6] |

Ōmura S, Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, et al. Genome sequence of an industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis: deducing the ability of producing secondary metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(21): 12215-12220. DOI:10.1073/pnas.211433198 |

| [7] |

Girot E. Nurse education in the new millennium. A review of current reports. Br J Perioper Nurs, 2001, 11(8): 352-361. |

| [8] |

Challinor VL, Bode HB. Bioactive natural products from novel microbial sources. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2015, 1354(1): 82-97. DOI:10.1111/nyas.12954 |

| [9] |

Challis GL, Hopwood DA. Synergy and contingency as driving forces for the evolution of multiple secondary metabolite production by Streptomyces species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2003, 100(S2): 14555-14561. |

| [10] |

Baltz RH. Gifted microbes for genome mining and natural product discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017, 44(4/5): 573-588. |

| [11] |

Vartoukian SR, Palmer RM, Wade WG. Strategies for culture of 'unculturable' bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2010, 309(1): 1-7. |

| [12] |

Brady SF, Simmons L, Kim JH, et al. Metagenomic approaches to natural products from free-living and symbiotic organisms. Nat Prod Rep, 2009, 26(11): 1488-1503. DOI:10.1039/b817078a |

| [13] |

Lok C. Mining the microbial dark matter. Nature, 2015, 522(7556): 270-273. DOI:10.1038/522270a |

| [14] |

Williamson LL, Borlee BR, Schloss PD, et al. Intracellular screen to identify metagenomic clones that induce or inhibit a quorum-sensing biosensor. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2005, 71(10): 6335-6344. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.10.6335-6344.2005 |

| [15] |

Uchiyama T, Abe T, Ikemura T, et al. Substrate- induced gene-expression screening of environmental metagenome libraries for isolation of catabolic genes. Nat Biotechnol, 2005, 23(1): 88-93. DOI:10.1038/nbt1048 |

| [16] |

Brady SF, Chao CJ, Handelsman J, et al. Cloning and heterologous expression of a natural product biosynthetic gene cluster from eDNA. Org Lett, 2001, 3(13): 1981-1984. DOI:10.1021/ol015949k |

| [17] |

Lim HK, Chung EJ, Kim JC, et al. Characterization of a forest soil metagenome clone that confers indirubin and indigo production on Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2005, 71(12): 7768-7777. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.12.7768-7777.2005 |

| [18] |

Brady SF, Chao CJ, Clardy J. New natural product families from an environmental DNA (eDNA) gene cluster. J Am Chem Soc, 2002, 124(34): 9968-9969. DOI:10.1021/ja0268985 |

| [19] |

Reddy BVB, Milshteyn A, Charlop-Powers Z, et al. eSNaPD: a versatile, web-based bioinformatics platform for surveying and mining natural product biosynthetic diversity from metagenomes. Chem Biol, 2014, 21(8): 1023-1033. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.06.007 |

| [20] |

Ziemert N, Podell S, Penn K, et al. The natural product domain seeker NaPDoS: a phylogeny based bioinformatic tool to classify secondary metabolite gene diversity. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(3): e34064. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0034064 |

| [21] |

Owen JG, Charlop-Powers Z, Smith AG, et al. Multiplexed metagenome mining using short DNA sequence tags facilitates targeted discovery of epoxyketone proteasome inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(14): 4221-4226. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1501124112 |

| [22] |

Chang FY, Ternei MA, Calle PY, et al. Targeted metagenomics: finding rare tryptophan dimer natural products in the environment. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(18): 6044-6052. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b01968 |

| [23] |

Kang HS, Brady SF. Arimetamycin a: improving clinically relevant families of natural products through sequence-guided screening of soil metagenomes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2013, 52(42): 11063-11067. DOI:10.1002/anie.201305109 |

| [24] |

Kallifidas D, Kang HS, Brady SF. Tetarimycin A, an MRSA-active antibiotic identified through induced expression of environmental DNA gene clusters. J Am Chem Soc, 2012, 134(48): 19552-19555. DOI:10.1021/ja3093828 |

| [25] |

Hover BM, Kim SH, Katz M, et al. Culture-independent discovery of the malacidins as calcium-dependent antibiotics with activity against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. Nat Microbiol, 2018, 3(4): 415-422. DOI:10.1038/s41564-018-0110-1 |

| [26] |

Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature, 2002, 417(6885): 141-147. DOI:10.1038/417141a |

| [27] |

Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis. Nat Biotechnol, 2003, 21(5): 526-531. DOI:10.1038/nbt820 |

| [28] |

Ikeda H. Natural products discovery from micro-organisms in the post-genome era. Biosci, Biotechnol, Biochem, 2017, 81(1): 13-22. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2016.1248366 |

| [29] |

Yaegashi J, Oakley BR, Wang CCC. Recent advances in genome mining of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters and the development of heterologous expression systems in Aspergillus nidulans. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 41(2): 433-442. DOI:10.1007/s10295-013-1386-z |

| [30] |

Mousa WK, Athar B, Merwin NJ, et al. Antibiotics and specialized metabolites from the human microbiota. Nat Prod Rep, 2017, 34(11): 1302-1331. DOI:10.1039/C7NP00021A |

| [31] |

Milshteyn A, Schneider JS, Brady SF. Mining the metabiome: identifying novel natural products from microbial communities. Chem Biol, 2014, 21(9): 1211-1223. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.08.006 |

| [32] |

Ziemert N, Alanjary M, Weber T. The evolution of genome mining in microbes - a review. Nat Prod Rep, 2016, 33(8): 988-1005. DOI:10.1039/C6NP00025H |

| [33] |

Medema MH, Fischbach MA. Computational approaches to natural product discovery. Nat Chem Biol, 2015, 11(9): 639-648. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.1884 |

| [34] |

Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016, 44(D1): D279-D285. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv1344 |

| [35] |

Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015, 43(W1): W237-W243. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv437 |

| [36] |

Machado H, Tuttle RN, Jensen PR. Omics-based natural product discovery and the lexicon of genome mining. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2017, 39: 136-142. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.025 |

| [37] |

Weber T, Welzel K, Pelzer S, et al. Exploiting the genetic potential of polyketide producing streptomycetes. J Biotechnol, 2003, 106(2/3): 221-232. |

| [38] |

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol, 1990, 215(3): 403-410. DOI:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 |

| [39] |

Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods, 2015, 12(1): 59-60. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.3176 |

| [40] |

Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res, 2011, 39(S2): W29-W37. |

| [41] |

Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, et al. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res, 2011, 39(S2): W339-W346. |

| [42] |

Blin K, Medema MH, Kazempour D, et al. antiSMASH 2.0-a versatile platform for genome mining of secondary metabolite producers. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(S1): W204-W212. |

| [43] |

Ling LL, Schneider T, Peoples AJ, et al. A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature, 2015, 517(7535): 455-459. DOI:10.1038/nature14098 |

| [44] |

Claesen J, Bibb M. Genome mining and genetic analysis of cypemycin biosynthesis reveal an unusual class of posttranslationally modified peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(37): 16297-16302. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1008608107 |

| [45] |

Spohn M, Kirchner N, Kulik A, et al. Overproduction of Ristomycin A by activation of a silent gene cluster in Amycolatopsis japonicum MG417-CF17. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2014, 58(10): 6185-6196. DOI:10.1128/AAC.03512-14 |

| [46] |

Cimermancic P, Medema MH, Claesen J, et al. Insights into secondary metabolism from a global analysis of prokaryotic biosynthetic gene clusters. Cell, 2014, 158(2): 412-421. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034 |

| [47] |

Thaker MN, Wang WL, Spanogiannopoulos P, et al. Identifying producers of antibacterial compounds by screening for antibiotic resistance. Nat Biotechnol, 2013, 31(10): 922-927. DOI:10.1038/nbt.2685 |

| [48] |

Thaker MN, Waglechner N, Wright GD. Antibiotic resistance-mediated isolation of scaffold-specific natural product producers. Nat Protoc, 2014, 9(6): 1469-1479. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2014.093 |

| [49] |

Tang XY, Li J, Millán-Aguiñaga N, et al. Identification of thiotetronic acid antibiotic biosynthetic pathways by target-directed genome mining. ACS Chem Biol, 2015, 10(12): 2841-2849. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00658 |

| [50] |

Rutledge PJ, Challis GL. Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2015, 13(8): 509-523. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro3496 |

| [51] |

Seyedsayamdost MR. High-throughput platform for the discovery of elicitors of silent bacterial gene clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2014, 111(20): 7266-7271. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1400019111 |

| [52] |

Moore JM, Bradshaw E, Seipke RF, et al. Use and discovery of chemical elicitors that stimulate biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces bacteria. Methods Enzymol, 2012, 517: 367-385. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-404634-4.00018-8 |

| [53] |

Locatelli FM, Goo KS, Ulanova D. Effects of trace metal ions on secondary metabolism and the morphological development of streptomycetes. Metallomics, 2016, 8(5): 469-480. DOI:10.1039/C5MT00324E |

| [54] |

Okada BK, Seyedsayamdost MR. Antibiotic dialogues: induction of silent biosynthetic gene clusters by exogenous small molecules. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2017, 41(1): 19-33. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuw035 |

| [55] |

Hosaka T, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Muramatsu H, et al. Antibacterial discovery in actinomycetes strains with mutations in RNA polymerase or ribosomal protein S12. Nat Biotechnol, 2009, 27(5): 462-464. DOI:10.1038/nbt.1538 |

| [56] |

Ochi K, Hosaka T. New strategies for drug discovery: activation of silent or weakly expressed microbial gene clusters. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013, 97(1): 87-98. DOI:10.1007/s00253-012-4551-9 |

| [57] |

Tanaka Y, Kasahara K, Hirose Y, et al. Activation and products of the cryptic secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters by rifampin resistance (rpoB) mutations in actinomycetes. J Bacteriol, 2013, 195(13): 2959-2970. DOI:10.1128/JB.00147-13 |

| [58] |

Rebets Y, Brötz E, Tokovenko B, et al. Actinomycetes biosynthetic potential: how to bridge in silico and in vivo?. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 41(2): 387-402. |

| [59] |

Rigali S, Anderssen S, Naômé A, et al. Cracking the regulatory code of biosynthetic gene clusters as a strategy for natural product discovery. Biochem Pharmacol, 2018, 153: 24-34. DOI:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.007 |

| [60] |

Kawai K, Wang GJ, Okamoto S, et al. The rare earth, scandium, causes antibiotic overproduction in Streptomyces spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2007, 274(2): 311-315. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00846.x |

| [61] |

Tanaka Y, Hosaka T, Ochi K. Rare earth elements activate the secondary metabolite-biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2010, 63(8): 477-481. DOI:10.1038/ja.2010.53 |

| [62] |

Craney A, Ozimok C, Pimentel-Elardo SM, et al. Chemical perturbation of secondary metabolism demonstrates important links to primary metabolism. Chem Biol, 2012, 19(8): 1020-1027. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.06.013 |

| [63] |

Pimentel-Elardo SM, Sørensen D, Ho L, et al. Activity-independent discovery of secondary metabolites using chemical elicitation and cheminformatic inference. ACS Chem Biol, 2015, 10(11): 2616-2623. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00612 |

| [64] |

König CC, Scherlach K, Schroeckh V, et al. Bacterium induces cryptic meroterpenoid pathway in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Chembiochem, 2013, 14(8): 938-942. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201300070 |

| [65] |

Shima J, Hesketh A, Okamoto S, et al. Induction of actinorhodin production by rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations that confer streptomycin resistance in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Bacteriol, 1996, 178(24): 7276-7284. DOI:10.1128/jb.178.24.7276-7284.1996 |

| [66] |

Bibb MJ. Regulation of secondary metabolism in streptomycetes. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2005, 8(2): 208-215. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.016 |

| [67] |

Srivatsan A, Wang JD. Control of bacterial transcription, translation and replication by (p)ppGpp. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2008, 11(2): 100-105. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.001 |

| [68] |

Xu J, Tozawa Y, Lai C, et al. A rifampicin resistance mutation in the rpoB gene confers ppGpp-independent antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Genet Genomics, 2002, 268(2): 179-189. |

| [69] |

Artsimovitch I, Patlan V, Sekine SI, et al. Structural basis for transcription regulation by alarmone ppGpp. Cell, 2004, 117(3): 299-310. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00401-5 |

| [70] |

McKenzie NL, Thaker M, Koteva K, et al. Induction of antimicrobial activities in heterologous streptomycetes using alleles of the Streptomyces coelicolor gene absA1. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2010, 63(4): 177-182. |

| [71] |

Zerikly M, Challis GL. Strategies for the discovery of new natural products by genome mining. Chembiochem, 2009, 10(4): 625-633. DOI:10.1002/cbic.200800389 |

| [72] |

Laureti L, Song LJ, Huang S, et al. Identification of a bioactive 51-membered macrolide complex by activation of a silent polyketide synthase in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2011, 108(15): 6258-6263. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1019077108 |

| [73] |

Orth P, Schnappinger D, Hillen W, et al. Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nat Struct Biol, 2000, 7(3): 215-219. DOI:10.1038/73324 |

| [74] |

Xu GM, Wang J, Wang LQ, et al. "Pseudo" γ-butyrolactone receptors respond to antibiotic signals to coordinate antibiotic biosynthesis. J Biol Chem, 2010, 285(35): 27440-27448. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.143081 |

| [75] |

Zhang YY, Zou ZZ, Niu GQ, et al. JadR and jadR2 act synergistically to repress jadomycin biosynthesis. Sci China Life Sci, 2013, 56(7): 584-590. DOI:10.1007/s11427-013-4508-y |

| [76] |

Bunet R, Song LJ, van Mendes M, et al. Characterization and manipulation of the pathway-specific late regulator AlpW reveals Streptomyces ambofaciens as a new producer of Kinamycins. J Bacteriol, 2011, 193(5): 1142-1153. DOI:10.1128/JB.01269-10 |

| [77] |

Lee HN, Huang JQ, Im JH, et al. Putative TetR family transcriptional regulator SCO1712 encodes an antibiotic downregulator in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2010, 76(9): 3039-3043. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02426-09 |

| [78] |

Takano E, Kinoshita H, Mersinias V, et al. A bacterial hormone (the SCB1) directly controls the expression of a pathway-specific regulatory gene in the cryptic type Ⅰ polyketide biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol, 2005, 56(2): 465-479. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04543.x |

| [79] |

Sidda JD, Song LJ, Poon V, et al. Discovery of a family of γ-aminobutyrate ureas via rational derepression of a silent bacterial gene cluster. Chem Sci, 2014, 5(1): 86-89. |

| [80] |

Siegl T, Tokovenko B, Myronovskyi M, et al. Design, construction and characterisation of a synthetic promoter library for fine-tuned gene expression in actinomycetes. Metab Eng, 2013, 19: 98-106. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2013.07.006 |

| [81] |

Seghezzi N, Amar P, Koebmann B, et al. The construction of a library of synthetic promoters revealed some specific features of strong Streptomyces promoters. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2011, 90(2): 615-623. DOI:10.1007/s00253-010-3018-0 |

| [82] |

Liu R, Deng ZX, Liu TG. Streptomyces species: ideal chassis for natural product discovery and overproduction. Metab Eng, 2018, 50: 74-84. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.015 |

| [83] |

Nepal KK, Wang GJ. Streptomycetes: surrogate hosts for the genetic manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters and production of natural products. Biotechnol Adv, 2019, 37(1): 1-20. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.10.003 |

| [84] |

Foley PL, Shuler ML. Considerations for the design and construction of a synthetic platform cell for biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2010, 105(1): 26-36. DOI:10.1002/bit.22575 |

| [85] |

Umenhoffer K, Fehér T, Balikó G, et al. Reduced evolvability of Escherichia coli MDS42, an IS-less cellular chassis for molecular and synthetic biology applications. Microb Cell Fact, 2010, 9: 38. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-9-38 |

| [86] |

Iwadate Y, Honda H, Sato H, et al. Oxidative stress sensitivity of engineered Escherichia coli cells with a reduced genome. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2011, 322(1): 25-33. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02331.x |

| [87] |

Yu BJ, Sung BH, Koob MD, et al. Minimization of the Escherichia coli genome using a Tn5-targeted Cre/loxP excision system. Nat Biotechnol, 2002, 20(10): 1018-1023. DOI:10.1038/nbt740 |

| [88] |

Csörgő B, Fehér T, Tímár E, et al. Low-mutation-rate, reduced-genome Escherichia coli: an improved host for faithful maintenance of engineered genetic constructs. Microb Cell Fact, 2012, 11: 11. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-11-11 |

| [89] |

Couto JM, McGarrity A, Russell J, et al. The effect of metabolic stress on genome stability of a synthetic biology chassis Escherichia coli K12 strain. Microb Cell Fact, 2018, 17: 8. DOI:10.1186/s12934-018-0858-2 |

| [90] |

Huang H, Zheng GS, Jiang WH, et al. One-step high-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in Streptomyces. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai), 2015, 47(4): 231-243. DOI:10.1093/abbs/gmv007 |

| [91] |

Ikeda H, Shin-Ya K, Omura S. Genome mining of the Streptomyces avermitilis genome and development of genome-minimized hosts for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 41(2): 233-250. |

| [92] |

Komatsu M, Uchiyama T, Ōmura S, et al. Genome-minimized Streptomyces host for the heterologous expression of secondary metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(6): 2646-2651. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914833107 |

| [93] |

Zweers JC, Barák I, Becher D, et al. Towards the development of Bacillus subtilis as a cell factory for membrane proteins and protein complexes. Microb Cell Fact, 2008, 7: 10. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-7-10 |

| [94] |

Reuß DR, Altenbuchner J, Mäder U, et al. Large-scale reduction of the Bacillus subtilis genome: consequences for the transcriptional network, resource allocation, and metabolism. Genome Res, 2017, 27(2): 289-299. |

| [95] |

Koo BM, Kritikos G, Farelli JD, et al. Construction and analysis of two genome-scale deletion libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Syst, 2017, 4(3): 291-305. |

| [96] |

Belda E, van Heck RGA, José Lopez-Sanchez M, et al. The revisited genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 enlightens its value as a robust metabolic chassis. Environ Microbiol, 2016, 18(10): 3403-3424. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13230 |

| [97] |

Nikel PI, de Lorenzo V. Pseudomonas putida as a functional chassis for industrial biocatalysis: from native biochemistry to trans-metabolism. Metab Eng, 2018, 50: 142-155. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.05.005 |

| [98] |

Nikel PI, Chavarría M, Danchin A, et al. From dirt to industrial applications: Pseudomonas putida as a Synthetic Biology chassis for hosting harsh biochemical reactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 2016, 34: 20-29. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.05.011 |

| [99] |

Komatsu M, Komatsu K, Koiwai H, et al. Engineered Streptomyces avermitilis host for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene cluster for secondary metabolites. ACS Synth Biol, 2013, 2(7): 384-396. DOI:10.1021/sb3001003 |

| [100] |

Yamada Y, Arima S, Nagamitsu T, et al. Novel terpenes generated by heterologous expression of bacterial terpene synthase genes in an engineered Streptomyces host. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2015, 68(6): 385-394. DOI:10.1038/ja.2014.171 |

| [101] |

Moya A, Gil R, Latorre A, et al. Toward minimal bacterial cells: evolution vs. design. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2009, 33(1): 225-235. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00151.x |

| [102] |

Cello J, Paul AV, Wimmer E. Chemical synthesis of poliovirus cDNA: generation of infectious virus in the absence of natural template. Science, 2002, 297(5583): 1016-1018. DOI:10.1126/science.1072266 |

| [103] |

Kodumal SJ, Patel KG, Reid R, et al. Total synthesis of long DNA sequences: synthesis of a contiguous 32-kb polyketide synthase gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004, 101(44): 15573-15578. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0406911101 |

| [104] |

Gibson DG, Benders GA, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, et al. Complete chemical synthesis, assembly, and cloning of a Mycoplasma genitalium genome. Science, 2008, 319(5867): 1215-1220. DOI:10.1126/science.1151721 |

| [105] |

Gibson DG, Benders GA, Axelrod KC, et al. One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(51): 20404-20409. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0811011106 |

| [106] |

Hutchison Ⅲ CA, Chuang RY, Noskov VN, et al. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science, 2016, 351(6280): aad6253. DOI:10.1126/science.aad6253 |

2019, Vol. 35

2019, Vol. 35