中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 张雨青, 曹佳宝, 赵娜, 王军

- Zhang Yuqing, Cao Jiabao, Zhao Na, Wang Jun

- 病毒组研究:微生物组研究新热点

- Virome: the next hotspot in microbiome research

- 生物工程学报, 2020, 36(12): 2566-2581

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2020, 36(12): 2566-2581

- 10.13345/j.cjb.200372

-

文章历史

- Received: June 23, 2020

- Accepted: November 10, 2020

- Published: December 23, 2020

2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

病毒是超显微、无细胞结构、专性活细胞内寄生的生命类群,它们广泛分布在多种环境(如海洋、湖泊、土壤等自然环境,以及肠道、呼吸道等宿主环境)中[1-4],种类丰富、数量庞大。据报道,在每毫升海水中大概具有106–109个病毒[5],在每克土壤与沉积物中大约含有109个病毒颗粒,其含量至少是其他微生物的10倍[2]。根据其感染宿主的差异,病毒可分为动物病毒、植物病毒、噬菌体和亚病毒(类病毒、拟病毒等)。它们具有丰富的遗传多样性,在宿主的基因可塑性方面起重要作用,并能够影响其他物种的多态性。

传统的病毒研究主要是采用宿主与病毒共培养的方法,但是这种方法仅能对已知能培养的病毒进行检测。近年来,随着高通量测序技术的不断进步,人们开始运用宏基因组策略来研究病毒组[6-7],此方法不仅能检测已知病毒,也能对未知病毒进行研究且不依赖于培养,能最大程度地还原环境中病毒的多样性。宏基因组学在病毒组学研究中最显著的影响是改变了人们对病毒多样性及种群结构的理解,并发现了大量的病毒新物种[8-9]。2016年,Nature杂志上发表一篇极具影响力的病毒组文章,该文章的作者David Paez-Espino及其团队利用宏基因组测序技术分析了来自3 042个不同地域样本超过5 Tb的数据,并评估病毒的全球分布、系统发育多样性和宿主特异性[10]。通过这项工作,他们将病毒序列的数量增加了50倍,由此确定的病毒多样性比已知的多了99%。Gregory等通过整合572个宏基因组或病毒组研究,收集了13 203个病毒基因组,从而构建了人类肠道病毒基因组数据库(Human Gut Virome Database,GVD)[11]。张永振等通过宏基因组策略研究了220多种无脊椎动物和脊椎动物的宏转录组,发现了与无脊椎动物相关的1 445种RNA病毒,大大改变了我们对RNA病毒圈的认识,包括RNA病毒组成、进化、起源、基因组结构以及与宿主的关系,弥补了以往病毒分类中存在的大量间隙。其中一些病毒与现有已知病毒的差异性之大,以至于需要重新被定义为新的病毒科[12-13]。此外,2005年报道的一项关于血液的病毒宏基因组学的开创性研究发现了与许多真核病毒相关的序列,且与数据库中的序列只有很小的相似性[14]。

相比于细菌和宿主来源的基因组,病毒基因组很小,因此病毒DNA只占宏基因组总DNA量的一小部分,导致宏基因组数据挖掘研究病毒组信息存在着数据量小、效率低等缺陷。并且,许多温和噬菌体整合在宿主基因组中,常以溶原状态存在。而病毒组富集能够一定程度区分整合的噬菌体和游离噬菌体的基因组,因此许多病毒组研究都采用了对病毒样颗粒(Virus-like particles,VLPs)进行富集的方式从而对病毒进行针对性的分析。目前,针对病毒组的分离富集已存在多种方法。例如,海洋病毒密度低,除纯化方法外,还必须对VLP进行浓缩,即切向流过滤(Tangential- flow filtration,TFF)[15]或FeCl3沉淀[16-17]等方法以获得足够的VLP密度用于测序[18]。除此之外,聚乙二醇(Polyethylene glycol,PEG)沉淀[19-20]、CsCl密度梯度离心[21]、超速离心[22]等都是典型的病毒分离富集方法。近年来,VLP富集方法被应用在各种环境的病毒组研究中。Tara海洋考察项目采集了全球海洋水体样本并对其进行了病毒样粒子的分离富集和测序分析,得到的Tara海洋病毒组(Tara Ocean Viromes,TOV)数据集,涵盖了全球上层海洋病毒组信息,并发现海洋病毒分布呈现明显的局部多样性[5]。研究人员在南极冰盖下的湖泊和热带的淡水水系中都通过病毒样粒子富集的方式发现了大量的未知病毒[23-24]。并且VLP方法也被广泛应用到水体中致病性病毒的检测当中,如水体中诺如病毒和粪便污染指示因子胡椒轻斑驳病毒(Pepper mild mottle virus,PMMoV)的检测[25-26]。在许多基于超滤或过滤方式获得人类肠道病毒样粒子的研究中发现,噬菌体的含量占据肠道病毒的绝大部分,同时许多真核RNA病毒也能被检测到,如星状病毒、杯状病毒等[27]。肠道病毒无法完全通过母婴传递过程转移,Rabia等发现新生儿的肠道病毒组仅有15%来自其母亲[28]。新生儿的肠道病毒在刚出生时几乎不存在,在出生一个月内,其病毒组种群主要为由最初在肠道内定植的某些先驱细菌诱导的噬菌体,在此后一段时间内病毒种群的变换则受到母乳喂养的调节[29]。随着年龄逐渐增长,成人的病毒组则表现出高度的个体差异性[30]。在土壤环境中,多采用PEG沉淀和切向流过滤(TFF)的方式获得病毒粒子。运用这种手段,研究人员发现了超过24 000种分布在全球土壤中的病毒序列及其潜在宿主[31-32]。而对中国东部沿海土壤进行的病毒组学分析则提供了一种海洋陆地过渡带病毒群落的初步轮廓[15]。此外Adriaenssens等对南极的土壤病毒组研究中发现病毒组的高度异质性与地理位置无关,但与土壤pH、钙含量有极大关联[33]。

然而,迄今为止尚缺乏完整、详细的针对病毒组分离富集的标准和比较。此外,病毒组数据分析也面临如下挑战:1)缺少类似于细菌和古菌中16S和真菌中18S/ITS等代表遗传多样性的保守基因来鉴定病毒组;2)缺乏完整的病毒基因组数据库,无法为病毒的分类和功能性研究提供基本参考。综上,本文将系统介绍VLP富集方法,并针对这些方法的优缺点进行评估。此外,我们也将对病毒组数据分析的流程进行简要概述,从而帮助传统生物学家以及刚刚踏足这一领域的研究者,促进病毒组研究领域的发展和进步。

1 VLP分离富集与处理VLP分离富集是病毒组测序的关键,样本中病毒组的真实情况取决于病毒样粒子的富集。因此,选择合适的VLP分离富集方法是研究者们首先要考虑的事情。

1.1 样品预处理在病毒颗粒富集之前,用于分离和存储样品的方法会显著影响病毒样颗粒的稳定性,从而影响病毒富集的质量。在准备用于病毒颗粒富集的样品时,如何破坏微生物和宿主细胞是一个需要考虑并十分棘手的问题。如果无法立即处理样品,则随后的细胞生长会污染样品。例如,收集的海水若未进行适当的处理或存储,那么在样品收集到病毒粒子处理期间发生的微生物生长会导致噬菌体暴发,最终导致数据集无法准确反映样品收集时的真实成分。通常在病毒样品中添加2%–5%的氯仿可以防止细胞的意外生长[34]。但是,添加溶剂会改变某些病毒颗粒的传染性和浮力密度,会给病毒粒子的收集和核酸提取产生极大影响。样品还可以在−80 ℃冷冻,以保留病毒颗粒并阻止细胞生长,这也是目前通常采用的方法。

1.2 基于过滤的VLP富集根据粒子的大小尺寸可以对病毒粒子进行分离富集,其原理是给定范围的孔径使符合范围的病毒粒子能顺利通过,而其他如细菌、真菌等颗粒直径较大的粒子不能通过,从而达到分离富集的效果。该方法的优点是简单易操作,使用普通的针孔过滤器(通常为0.22 μm或0.45 μm)就可以实现对病毒粒子的富集。Legoff等[35]运用此方法成功在肠道中富集得到真核病毒,并证明其对造血干细胞移植后患者健康的影响。但是,孔径大小的选择会影响病毒粒子的富集效果,并且过滤器也经常会因其他杂质堵塞导致过滤变得困难。

切向流过滤(TFF)经常用于水环境中病毒粒子的分离[17]。该方法可以保留较大的颗粒并去除多余的液体(即滤液),将样品中的病毒颗粒浓缩为较小的体积。使用压力迫使样品通过中空纤维过滤器的孔,从而丢弃通过过滤器的小颗粒,样本中成分(大于过滤器孔径)则被收集到一个储水池中,然后循环通过过滤器多次,达到富集的目的。为了确保这些较大的颗粒在推向过滤器孔时不会破裂,使用油压计将系统内的压力保持在6.89×104 Pa以下。与冲击式过滤器相比,该过滤器的表面积使大量(数十至数百升)的滤液快速通过,并且不易堵塞。此外,TFF可用于产生无病毒颗粒的滤液。例如,在使用100–300 kDa TFF滤液进行颗粒分离之前,可以从宿主组织表面冲洗掉表面病毒[36]。

1.3 基于离心的VLP富集超速离心的方法可用于不同环境中病毒粒子的富集,包括差速离心和密度梯度离心[37]。差速离心是根据病毒粒子的大小、密度及形状对其进行沉降富集,较大的颗粒将先于较小的颗粒沉降,而密度较大的颗粒将在密度较小的颗粒之前沉降,而不对称的颗粒比相同质量和密度的球形颗粒沉降得更慢。但是,这种分离并不干净,因为从样品顶部沉淀颗粒所需的离心力也会从底部沉淀小颗粒。所以前期过滤掉非病毒粒子非常关键,同时离心力也需要足够大才能保证小的病毒粒子的沉降[22]。近期,我们应用此方法成功从健康人类粪便中富集得到了大量的噬菌体病毒[38]。但是,该方法有一个缺陷就是在离心的过程可能会破坏病毒粒子。

在密度梯度离心过程中,不同密度的同一介质可在同一个容器中旋转,导致各种密度的病毒粒子集中在与其密度相同的介质中,从而达到分离富集的目的。因此,高密度的介质,例如碱金属盐(例如CsCl)或小的疏水性有机化合物(例如蔗糖)通常被用于密度梯度离心。根据病毒粒子的最终用途(例如宏基因组测序与病毒培养研究),选择用于密度梯度离心的介质类型至关重要,因为每种介质对粒子完整性和感染性都有不同的影响。如何选择离心的溶剂和速度以及梯度介质的类型和数量完全取决于目标病毒的密度。无论选择哪种介质,均应使用与原始样品相同的缓冲液类型进行梯度洗脱,用于产生梯度的缓冲液必须首先使用0.02 μm过滤器进行纯化以确保外部病毒或其他微生物不会污染所得的馏分。其中,CsCl密度梯度离心是应用最为广泛的富集方法[39]。但是,该方法对离心机和实验操作要求高,适合收集单一病毒粒子。富集环境中多种病毒粒子时会有较宽区带,增加实验难度。

1.4 其他富集方法大量的研究已证明,铁离子[40]、铝[41]和聚电解质[42]能有效地沉淀和去除废水中的病毒。依据以上原理,John等[43]引入了使用FeCl3沉淀技术从海水中浓缩病毒的方法。此方法可以回收92%–95%的病毒粒子,并且在冰川和深海的样品中得到了很好的应用[44-45]。与TFF相比,该方法的病毒回收率更高且更加经济。除此之外,PEG也是一种重要的无需进行超速离心的病毒富集方法。PEG能够沉淀蛋白质,而噬菌体的外壳的主要成分就是蛋白质,因此PEG能够将噬菌体从溶液中沉淀下来,从而达到富集的效果。PEG沉淀法很久之前就已经应用于各种环境样本中病毒粒子的富集[46]。近期,Shkoporov等[20]应用PEG沉淀病毒的原理开发了针对肠道噬菌体组的富集方法。值得注意的是,PEG纯化病毒的过程中会形成粘性高分子化合物,通过缓冲溶液交换方法很难去除PEG,导致病毒粒子富集失败[47]。

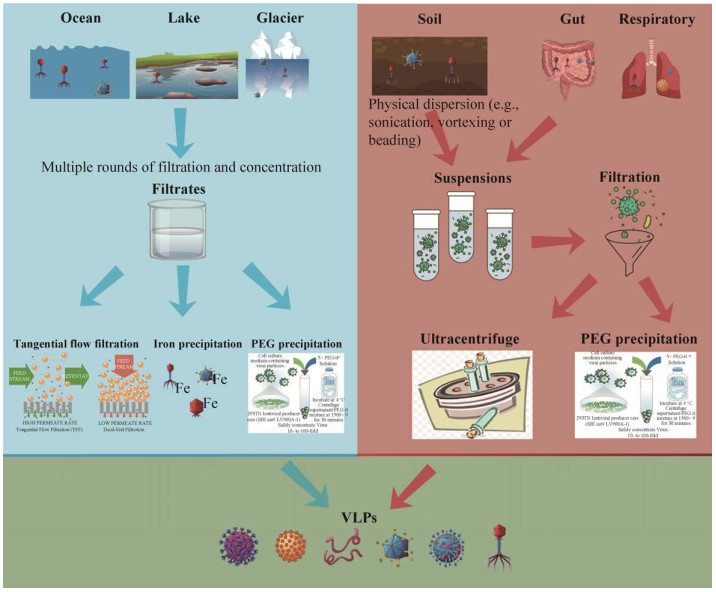

1.5 富集方式的应用由于不同环境样本的性质和含有病毒浓度的差异,VLP富集时也会有针对性策略(图 1)。从海洋、湖泊或冰川中获得的样本体积一般多达几十升,在富集过程中通常先用大孔径过滤器进行粗过滤,过滤掉浮游生物和其他微生物并去除大量的水,然后使用TFF/FeCl3/PEG的方法浓缩沉淀病毒颗粒。值得注意的是,样本采集时常受到外界因素的干扰(如温度和压力),从而影响水体内噬菌体种类和数目,不能反映真实状态。因此,在获得样本后应及时处理。

|

| 图 1 不同环境样本病毒粒子富集示意图 Fig. 1 Schematic of virus-like particles enrichment in different samples. Enrichment methods for water samples in the blue background include TFF, FeCl3 and PEG precipitation methods. Viral enrichment methods for soil and human intestinal and respiratory samples, including ultracentrifugation and PEG precipitation, are shown in the brown background. The green background part indicates enriched virus-like particles. |

| |

土壤样本为固体状态,需要研究人员先使用病毒重悬方法进行处理。使用物理分散(如超声处理、涡旋或珠击)的方式将土壤样本中的病毒样粒子重悬,然后将洗脱液通过离心过滤的方式去除其他大颗粒后再用PEG沉淀或基于离心的方式进行富集,值得特别注意的是,Gareth Trubl等发现在超滤浓缩时添加1%牛血清白蛋白(Bovine albumin,BSA)会提高病毒得率[48-50]。人体肠道样本与土壤样本类似,经缓冲液重悬、粗离心和过滤等步骤后可采取PEG沉淀或基于离心的方式进行富集。人体其他样本则可以根据样本材料采取合适的方法。

1.6 病毒核酸扩增与测序病毒粒子的核酸提取可采用传统的苯酚/氯仿/异戊醇法或成熟的病毒纯化试剂盒(如QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit,Qiagen)。有时,为满足测序建库对核酸量的需求,通常需要对病毒核酸进行扩增。但是,扩增方法不同会对测序结果产生较大影响[51]。例如,随机扩增只针对双链DNA;多重置换法倾向于扩增单链DNA且不均匀扩增线性基因组;衔接子扩增通常需要较高模板浓度。因此,每一种方法都有自己的局限性,研究者需要根据实验目的选取合适的扩增方法。随着测序技术的不断进步,常用的测序平台包括Illumina、Ion torrent、Solid、454 Roche、PacBio和Oxford Nanopore。其中,以Illumina为首的二代测序技术具有通量高、价格便宜等优势被广泛应用。但是,测序产生的序列较短(200 bp左右),对重复序列较多、高度嵌合的基因组组装带来很大挑战。至此,相比二代,三代测序技术(PacBio和Oxford Nanopore)能产生更长的序列从而有利于基因组组装,但是其价格较高且序列的准确度需要进一步提升。

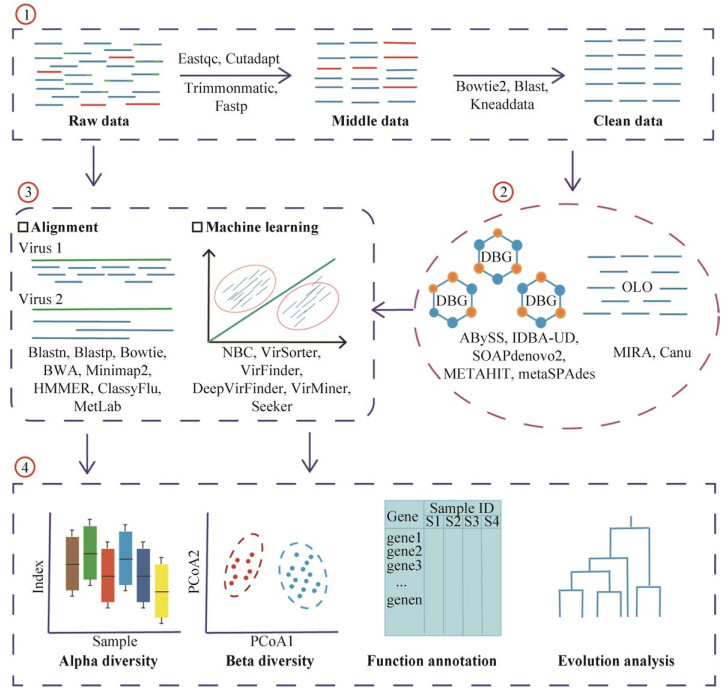

2 病毒宏基因组生物信息分析病毒宏基因组学主要用于对环境和生物样品中的病毒进行研究。它主要利用下一代测序技术,分析病毒序列以阐明病毒对人类健康及环境的影响。与扩增子测序不同,宏基因组学是直接从环境样品中获取和研究遗传物质,使人们对微生物世界的多样性和功能有全新的认识。其中,涉及到的重要环节是对测序数据的分析,一般包括以下步骤:1)数据质量控制和过滤,包括去除测序过程中添加的引物序列、接头序列以及低质量的序列。同时,过滤非病毒基因组序列,如人类样本中的大量宿主基因组序列;2)病毒基因组组装;3)病毒分类鉴定;4)病毒多样性分析及功能注释等(图 2)。接下来,我们将对这些步骤中涉及的工具、方法及数据库进行详细介绍,同时针对不同情况给出相应的分析策略。

|

| 图 2 病毒组生物信息分析流程 Fig. 2 Schematic pipeline of bioinformatic analysis for virome. As shown in the figure, the analysis for virome is divided into 4 parts: Data filtering and cleaning, including filtering out adapters, primers and low quality sequences, while removing environmental contamination such as host sequences; De novo assembly of genome, involving a total of two algorithms (DBG and OLO); Viral classification and identification, divided into two approaches, one is a reference-based comparison method and the other is a machine learning-based method; Downstream analysis, including alpha and beta diversity analysis, gene function annotation and viral evolution. Of note, the bottom of the first three parts of the figure represents the software used in the process. |

| |

获得测序数据(Raw data)后,首先应当对数据进行质量控制。在文库构建的过程中会人为添加引物和接头序列,且在测序过程中也会引入低质量或错误序列。为避免对下一步的分析造成影响,需要对这些序列进行排除。目前,常用的有FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc)、Cutadapt[52]、Trimmomatic[53]和Fastp[54]等(表 1)。FastQC是一种基于java的快速测序质量评估软件,支持Fastq、SAM、BAM等文件格式,最终的结果以网页HTML格式展示。Cutadapt具备去除引物和接头序列以及多聚腺苷酸尾等功能。Trimmomatic是一款针对Illumina测序数据的质量控制软件,它提供了一系列参数用于去除接头序列和低质量序列。而Fastp是由C++语言编写的同时具备FastQC、Cutadapt和Trimmomatic三种软件功能的质量控制软件,支持多线程且运行速度更快。质控后的不同样本测序数据,通常需要过滤掉非病毒序列以免影响后续分析,尤其在人体样本会有一定比例的人基因组序列。该步骤通常采用基于比对的方法去除,如应用Bowtie2[55]、BLAST[56]等软件将数据比对到宿主或细菌基因组以去除非病毒序列并得到纯净的数据(Clean data)。另外,KneadData (https://github.com/biobakery/biobakery/wiki/kneaddata)是一款常用的旨在对宏基因组测序数据进行质量控制的工具,可以用于去除环境样本中的宿主污染。

2.2 病毒基因组de novo组装截至当前,仍有大量的病毒没有被注释,且在参考数据库中很难找到同源物。因此,对病毒组的研究很大程度上依赖于基因组的从头组装,以还原其组成及功能等信息。根据不同的组装策略,可将组装软件分为两大类[57](表 1):一类是基于overlap-layout-consensus (OLC)方法的组装,如MIRA[58]、Canu[59]等适用于长读序列的拼接与组装;另一类则是基于de-Bruijn-graph (DBG)方法的组装,这也是宏基因组组装最常用方法,软件有ABySS[60]、IDBA-UD[61]、SOAPdenovo2[62]、METAHIT[63]、metaSPAdes[64]等适合短读序列的组装。

| Name | Description | Web address | Reference |

| FastQC | Quality control of fastq or fasta data | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ | |

| Cutadapt | Removal of primer, adapter sequences and ployA tails | https://github.com/marcelm/cutadapt/ | [52] |

| Trimmomatic | Filtering of low-quality sequences | http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic | [53] |

| Fastp | Removal of adapter sequences and filtering of low-quality sequences | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp | [54] |

| KneadData | A tool designed to perform quality control on metagenomic sequencing data | https://github.com/biobakery/biobakery/wiki/kneaddata | |

| MIRA | Assembly of short-read sequences based on the overlap-layout-consensus method | http://www.chevreux.org/projects_mira.html | [58] |

| Canu | A tool designed for high-noise single-molecule sequencing | https://github.com/marbl/canu | [59] |

| ABySS | Assembly of short-read sequences based on the de-Brujin-graph method; faster parallel calculation support | https://www.bcgsc.ca/resources/software/abyss | [60] |

| IDBA-UD | Assembly of short-read sequences based on the de-Brujin-graph method; faster parallel calculation support | https://github.com/loneknightpy/idba | [61] |

| SOAPdenovo2 | Assembly of short-read sequences based on the de-Brujin-graph method | https://github.com/aquaskyline/SOAPdenovo2 | [62] |

| METAHIT | Assembly tools based on the de-Bruijn-graph method for single-cell and metagenomic data assembly | https://github.com/voutcn/megahit | [63] |

| metaSPAdes | Assembly tools based on the de-Bruijn-graph method for metagenomic data assembly; support for mixed assembly of short-read and long-read sequence | http://cab.spbu.ru/software/meta-spades/ | [64] |

MIRA是一种支持全基因组霰弹枪测序、EST及RNA-Seq测序数据的组装软件,同时支持Sanger、454 Roche、Illumina、Ion torrent和PacBio等不同测序的混合组装,不过PacBio仅限于CCS (Circular Consensus Sequencing)读取或错误校正的CLR (Continuous Long Reads)数据。Canu专门应用于高噪声的单分子测序如PacBio和Nanopore数据的组装,包括4个主要步骤:使用MHAP算法[65]检测重叠序列;生成校正后共有序列;修剪校正后的序列;组装。ABySS是一种针对双端短读序列的从头组装软件,允许进行组装算法并行计算,节省大量时间。基于IDBA算法,IDBA-UD软件更适用于高度不均匀测序深度的短读序列的组装,其使用多个深度相关阈值去除了低深度和高深度区域中的错误k-mers,并使用具有末端信息的局部组装技术解决了低深度段重复区域的分支问题。SOAPdenovo2是一款专门针对Illumina GA测序数据的组装软件,主要用于动植物等大型基因组的组装,也可以用于细菌或真菌基因组的组装。相比于SOAPdenovo2软件,MEGAHIT是一款运行速度更快、内存消耗更小的组装软件,其主要适用于宏基因组的组装,同时也支持单个基因组和单细胞测序数据的组装。MetaSPAdes是目前宏基因组组装指标最好的一款软件,尤其是在株水平上的组装,同时它也支持PacBio、Nanopore和Sanger测序数据的混合组装。

2.3 病毒分类鉴定根据分类方法的原理不同,病毒宏基因组的系统学分类(Taxonomic classification)可分为两种(表 2)。一种是基于相似性比对的分类方法,该方法通常是将测序原始reads数据或组装好的contigs数据与参考病毒基因组进行比对。常用的软件有BLAST算法中的Blastn和Blastx。但是,应用该方法大部分的从头组装的序列会被定义为未知病毒,并且当有大量的宏基因组数据去比对核酸和蛋白数据库时,该方法会非常耗时。因此,近年来出现了针对测序原始数据比对方法,如Bowtie[66]、BWA[67]、Minimap2[68]等,通常它们也会应用于过滤步骤且仅比对核酸序列。另外,远源蛋白质之间的同源性比较,可采用基于隐马尔科夫模型(Hidden Markov model, HMM)的方法去鉴定保守的蛋白结构域,软件主要有HMMER[69]、ClassyFlu[70]、Virsorter[71]、MetLab[72]等。另一种方法是基于基因组组成(如GC含量、密码子和k-mers使用等)应用机器学习或深度学习算法进行病毒分类的方法。应用这类方法的软件有NBC[73]、VirFinder[74]、DeepVirFinder[75]、ViraMiner[76]、Seeker[77]等。NBC是最早的应用朴素贝叶斯算法对病毒进行分类的网页服务器。VirFinder基于k-mers的使用频率应用机器学习算法来鉴定病毒序列。另外,DeepVirFinder、ViraMiner和Seeker软件都是基于深度学习的算法进行病毒序列鉴定。这类方法的优势是不涉及同源比对,速度更快。但是相比于基于相似性比对的方法,该法的准确性较低且很大程度上依赖于序列的长度。

| Name | Description | Web address | Reference |

| Viral classification | |||

| Bowtie | Short reads sequence alignment | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml | [55] |

| BWA | Short reads sequence alignment | http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ | [67] |

| Minimap2 | Long reads sequence alignment; faster speed | https://github.com/lh3/minimap2 | [68] |

| HMMER | Sequence homology search based on HMM | http://hmmer.org/ | [69] |

| ClassFlu | Influenza virus identification | http://bioinf.uni-greifswald.de/ClassyFlu | [70] |

| Virsorter | Bacteriaphage prediction | https://github.com/simroux/VirSorter | [71] |

| MetLab | In silico experimental DESIGN, SImulation and analysis tool for viral metagenomics studies | https://github.com/norling/metlab | [72] |

| NBC | näive bayes classification tool to classify reads originating from viral and fungal organisms | http://nbc.ece.drexel.edu/ | [73] |

| VirFinder | A novel k-mer based tool for identifying viral sequences from assembled metagenomic data | https://github.com/jessieren/VirFinder | [74] |

| DeepVirFin-der | Identifying viruses from metagenomic data by deep learning | https://github.com/jessieren/DeepVirFinder | [75] |

| ViraMiner | CNN based classifier for detecting viral sequences among metagenomic contigs | https://github.com/NeuroCSUT/ViraMiner | [76] |

| Seeker | A python library for discriminating between bacterial and phage genomes | https://github.com/gussow/seeker | [77] |

| Viral genome annotation | |||

| VAPiD | Viral annotation and identification pipeline | https://github.com/rcs333/VAPiD | [90] |

| VIGOR | An annotation program for small viral genomes | http://www.jcvi.org/vigor | [91] |

| VGAS | Viral genome annotation system combing ab initio method and similarity-based method | http://cefg.uestc.cn/vgas/ | [92] |

| VIGA | De novo viral genome annotator | https://github.com/EGTortuero/viga | [93] |

| Evolution analysis | |||

| MEGA | Phylogentic tree construction | https://www.megasoftware.net/ | [94] |

| FastTree | Phylogentic tree construction | http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/ | [95] |

| IQ-TREE | Phylogentic tree construction | http://www.iqtree.org/ | [96] |

| ggtree | Phylogenetic tree beautification; R package | https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/ggtree | [97] |

| GraPhlAn | Evolutionary branching diagram visualization | https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/graphlan | [98] |

| TreeView | Phylogenetic tree visualization and editing | https://treeview.co.uk/ | [99] |

| FigTree | Phylogenetic tree visualization and editing | https://github.com/rambaut/figtree | |

| ITOL | Phylogenetic tree visualization, online editing and beautification support | https://itol.embl.de/ | [100] |

用于病毒分类鉴定的病毒基因组参考数据库有很多,最常用的数据库为NCBI中的病毒基因组数据库,截至2020年6月,该数据库中存储了9 732个完整的病毒基因组(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/GenomesGroup.cgi?taxid=10239)。virSITE是一个整合的病毒基因组数据库,截至2020年2月,该数据库中包括了9 255种病毒(11 988个病毒基因组序列)[78]。这两个数据库包含了目前能够鉴定到的所有病毒基因组,为研究各种环境样本中病毒的全貌提供了重要参考,同时也为病毒的分类研究奠定了数据基础。一些真核病毒(如流感病毒、埃博拉病毒、乙肝病毒以及2020年暴发的新型冠状病毒等)常常作为病原感染人类细胞,造成严重的人类疾病甚至死亡。针对这类病毒组的研究,专一性病毒基因组数据库应运而生。例如,RVDB数据库[79]提供除细菌病毒(噬菌体)外所有的真核病毒、类病毒和病毒相关序列,如内源性非逆转录病毒元件、内源性逆转录病毒和逆转录病毒等。ViPR数据库(https://www.viprbrc.org)[80]是一个专门针对冠状病毒的一站式资源库和在线分析工具。它收集包括序列、基因、蛋白注释、蛋白3D结构、免疫表位、临床和检测等数据,同时提供序列比对、系统进化分析、序列变异测定和引物设计等实用工具。此外,还有一些侧重于特定病毒群体的数据库,如流感病毒数据库OpenFluDB[81]和Influenza Research Database (IRD)[82]、埃博拉病毒知识库Ebola-KB[83]、乙肝病毒数据库HBVdb[84]等。OpenFluDB是一个开放式的流感病毒数据库,其包含了病毒基因组和蛋白序列数据,以及来自25 000多个分离物的流行病学数据。IRD数据库是由美国过敏症和传染病研究所(National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases,NIAID)建立,专门研究流感病毒的综合数据库。它提供了关于流感病毒的各种数据,同时也提供用于流感数据挖掘的分析可视化工具。Ebola-KB是一个专一收集埃博拉病毒相关信息的整合知识库。HBVdb为研究人员研究乙肝病的遗传变异和病毒对治疗的耐药性提供丰富的资源,截至2020年7月该数据库已包含89 543个条目。

2.4 多样性分析与细菌宏基因组多样性分析一致,病毒物种多样性也分为3类:alpha多样性、beta多样性、gamma多样性。Alpha多样性是指在一个确定的栖息环境、研究区域或者样本内存在物种的个数(Species richness;物种丰富度)以及每个物种的数量和分布(Species evenness;物种均匀度),也被称为样本内物种多样性。度量方法有Shannon指数[85]、Chao1[86]、ACE指数[87]等。Beta多样性指与环境复杂梯度和环境模式相关的群体组成变化程度或群体分化程度,也被称为样本间的多样性。多种距离方法被用于表示beta多样性,常用的方法有Bray-Curtis距离(基于物种的数量测量样本间相异度)、Jaccard距离(基于物种的存在与否测量样本间相异度)和UniFrac距离(结合了进化信息来测量样本间相异度)等[88]。Gamma多样性是指大区域(地理区域)上总的多样性,其包含了alpha多样性和beta多样性。另外,一些分析技术的限制,如病毒注释不准确、缺乏系统发育标记基因以及个体差异大等,会使病毒的多样性研究复杂化,从而产生大量未被正确分类注释的序列,或者仅在几个样本中鉴定到特异的病毒,生成稀疏数据,即包含大量零的数据矩阵。因此,随后的分析应格外注意。统计分析及可视化大多使用R语言,常用的R包可参考刘永鑫等[89]的报道。

2.5 功能注释及进化分析为确定病毒的功能,病毒基因组注释是常用的分析手段。目前针对病毒基因组注释的工具有VAPiD[90]、VIGOR[91]、VGAS[92]、VIGA[93]等(表 2)。VAPiD通过与GenBank数据库比较来对每个输入的病毒序列进行注释,并提供元数据(metadata),从而简化向GenBank提交完整病毒基因组序列的过程。VIGOR通过首先识别其集合中最相关的参考数据库,然后将该数据库中所有参考蛋白和成熟肽序列与输入序列进行比较,以确定其注释,从而对输入序列进行注释。但是,这两个程序都会检测并报告某些类型的意外错误,例如过早的终止密码子。VGAS结合ORF计算预测和序列相似比对这两种策略对病毒基因组进行注释。VIGA对于大型宏基因组的注释速度更快,且能够识别不同类型RNA及CRISPR重复元件。

进化分析不仅能提供病毒之间亲缘关系,同时也能追溯病毒物种的起源。其核心步骤是构建系统发育树。而系统发育树的构建可分为两种:基于距离的方法和基于特征的方法。基于距离的方法包括具有算术平均值的非加权成对组方法(UPGMA)、邻接法(NJ)、最小演化法(ME)和Fitch-Margoliash方法(FM)。基于特征的方法包括最大简约方法(MP)和最大似然方法(ML)。比较计算速度,NJ方法优于当前正在使用的其他系统发育树构建方法。该方法可以使用自展法(bootstrap)轻松处理大量序列,而MP、ME和ML方法会检查所有可能的拓扑结构分别搜索MP、ME和ML树,因此耗费时间较多。系统发育树的构建可以使用MEGA[94]、FastTree[95]、IQ-TREE[96]等软件。另外,构建好的系统发育树可以应用ggtree[97]、GraPhlAn[98]、TreeView[99]、FigTree (https://github.com/rambaut/figtree/)和在线网站ITOL[100]对其进行美化(表 2)。

3 总结与展望相比于细菌和宿主来源的基因组,病毒基因组很小且仅占微生物总量的一小部分,因此病毒颗粒的富集是非常有必要的。随着病毒组研究的快速发展,已经出现了许多富集病毒的方法。这些富集方法根据富集过程中应用的病毒物理学特性,大致分为3类:基于过滤的病毒颗粒富集方法;基于离心的病毒颗粒富集方法;其他富集方法。每一种富集方法都有各自的适应性和优缺点,充分了解这些富集方法的原理及优缺点,对于实验方案的设计和后续数据的分析具有重要的参考意义。另外,根据研究目的和实验对象的不同,仅用一种方法可能不足以达到富集全部病毒的目的,所以这时候需要综合考虑选取的病毒颗粒富集方法或者配合使用多种富集方法,最终尽可能呈现各类样品中真实的病毒丰度和分布。例如,海洋病毒组研究应先过滤藻类等大颗粒物质,然后结合普通过滤和TFF方法进一步浓缩病毒粒子。有时为得到更加纯净且高浓度的病毒粒子,有些研究会再使用PEG和FeCl3沉淀法进行富集[5, 17]。而在土壤和人体肠道病毒组研究中,实验人员可以采取过滤与超速离心或PEG沉淀等多种方式相结合的策略,以最大程度地获得更多的病毒颗粒。应用各类病毒粒子富集方法,研究人员大大提高了病毒组研究的分析效率和精确度,并在多种环境得到应用,如Tara海洋病毒组(TOV)[5]、太平洋病毒组(POV)[17]、新生儿肠道病毒组[28]、南非和中国东部沿海地区土壤病毒群落基因组[15, 32]等。然而,目前的实验方法常需要较大样本量且不能直观地观察富集得到的病毒粒子,仅能通过测序手段来检验病毒粒子的多样性。对于一些稀有或特殊的样本,常常不能满足需求。最近开发的基于流式细胞仪的方法可以通过用荧光染料标记噬菌体从背景微生物群中分离出VLPs[101],然后根据VLPs的大小和荧光水平选择VLPs,并使用荧光激活细胞分选法从样品中去除。另外,实验的批次效应也需格外注意,研究者需严格遵守实验步骤,规避每一步由于操作造成较大误差的风险。

随着宏基因组分析技术和测序技术的发展,人们已经获得大量的病毒数据。例如,整合的人类肠道病毒数据(Human Gut Virome Database,GVD)[11]、脊椎动物和无脊椎动物病毒组[12-13]、深海热泉泉口病毒组[102]等,极大地扩充了病毒的多样性进而加深了研究人员对病毒组学的理解。同时,高通量测序会产生大量的基因组数据,进而增大对生物信息工具和算法开发的需求。至此,我们对病毒宏基因组学数据分析的一般流程进行综述,包括了数据预处理、病毒基因组组装、物种鉴定、多样性分析、功能注释及进化分析,并针对每一步骤所需常用生物信息分析工具进行了简要介绍。由于缺乏保守的系统发育标记基因(如细菌和古菌的16S rRNA),且测序得到的大量序列在已知病毒基因组数据库中难以找到对应物[103],致使病毒物种的鉴定仍然是当前最具挑战的分析步骤。虽然机器学习和人工智能领域的飞速发展,使得基于基因组组成的病毒物种鉴定工具逐渐增多,但是相比于基于比对的鉴定方法,其灵敏度和准确性还有待进一步提高。此外,相比传统的基于培养的病毒研究,病毒宏基因组学虽然能检测出更多的病毒,极大地扩展了人们对病毒丰度和多样性的认识,但是仍存在分辨率低的缺点,难以区分相似度很高的序列。基于培养的病毒研究结合透射电子显微观察的方法不仅能够识别病毒形态,还能够鉴定噬菌体的宿主。单一病毒的研究能够揭示病毒群体的遗传异质性。因此,宏病毒组学应与单病毒基因组学、分离培养与显微镜观测结合来探索病毒暗物质。

| [1] |

Rampelli S, Turroni S, Schnorr SL, et al. Characterization of the human DNA gut virome across populations with different subsistence strategies and geographical origin. Environ Microbiol, 2017, 19(11): 4728-4735. |

| [2] |

Williamson KE, Fuhrmann JJ, Wommack KE, et al. Viruses in soil ecosystems: an unknown quantity within an unexplored territory. Ann Rev Virol, 2017, 4: 201-219. |

| [3] |

Wommack KE, Nasko DJ, Chopyk J, et al. Counts and sequences, observations that continue to change our understanding of viruses in nature. J Microbiol, 2015, 53(3): 181-192. |

| [4] |

Zhang YZ, Shi M, Holmes EC. Using metagenomics to characterize an expanding virosphere. Cell, 2018, 172(6): 1168-1172. |

| [5] |

Brum JR, Ignacio-Espinoza JC, Roux S, et al. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viralcommunities. Science, 2015, 348(6237): 1261498. |

| [6] |

Nooij S, Schmitz D, Vennema H, et al. Overview of virus metagenomic classification methods and their biological applications. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 749. |

| [7] |

Rose R, Constantinides B, Tapinos A, et al. Challenges in the analysis of viral metagenomes. Virus Evol, 2016, 2(2): vew022. |

| [8] |

Coutinho FH, Silveira CB, Gregoracci GB, et al. Marine viruses discovered via metagenomics shed light on viral strategies throughout the oceans. Nat Commun, 2017, 8: 15955. |

| [9] |

Rascovan N, Duraisamy R, Desnues C. Metagenomics and the human virome in asymptomatic individuals. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2016, 70: 125-141. |

| [10] |

Paez-Espino D, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Pavlopoulos GA, et al. Uncovering Earth's virome. Nature, 2016, 536(7617): 425-430. |

| [11] |

Gregory AC, Zablocki O, Zayed AA, et al. The gut virome database reveals age-dependent patterns of virome diversity in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe, 2020, 28: 1-17. DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2020.08.003 |

| [12] |

Shi M, Lin XD, Tian JH, et al. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature, 2016, 540(7634): 539-543. |

| [13] |

Shi M, Lin XD, Chen X, et al. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature, 2018, 556(7700): 197-202. |

| [14] |

Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Method for discovering novel DNA viruses in blood using viral particle selection and shotgun sequencing. Biotechniques, 2005, 39(5): 729-736. |

| [15] |

Yu DT, Han LL, Zhang LM, et al. Diversity and distribution characteristics of viruses in soils of a marine-terrestrial ecotone in east China. Microb Ecol, 2018, 75(2): 375-386. |

| [16] |

Bahram M, Hildebrand F, Forslund SK, et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature, 2018, 560(7717): 233-237. |

| [17] |

Hurwitz BL, Sullivan MB. The Pacific Ocean Virome (POV): a marine viral metagenomic dataset and associated protein clusters for quantitative viral ecology. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(2): e57355. |

| [18] |

Hurwitz BL, Deng L, Poulos BT, et al. Evaluation of methods to concentrate and purify ocean virus communities through comparative, replicated metagenomics. Environ Microbiol, 2013, 15(5): 1428-1440. |

| [19] |

Castro-Mejía JL, Deng L, Vogensen FK, et al. Extraction and purification of viruses from fecal samples for metagenome and morphology analyses. Methods Mol Biol, 2018, 1838: 49-57. |

| [20] |

Shkoporov AN, Ryan FJ, Draper LA, et al. Reproducible protocols for metagenomic analysis of human faecal phageomes. Microbiome, 2018, 6: 68. |

| [21] |

Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J, et al. The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res, 2011, 21(10): 1616-1625. |

| [22] |

Thurber RV, Haynes M, Breitbart M, et al. Laboratory procedures to generate viral metagenomes. Nat Protocols, 2009, 4(4): 470-483. |

| [23] |

López-Bueno A, Tamames J, Velázquez D, et al. High diversity of the viral community from an Antarctic lake. Science, 2009, 326(5954): 858-861. |

| [24] |

Gu XQ, Tay QXM, Te SH, et al. Geospatial distribution of viromes in tropical freshwater ecosystems. Water Res, 2018, 137: 220-232. |

| [25] |

Fumian TM, Fioretti JM, Lun JH, et al. Detection of norovirus epidemic genotypes in raw sewage using next generation sequencing. Environ Int, 2019, 123: 282-291. |

| [26] |

Rosiles-González G, Ávila-Torres G, MorenoValenzuela OA, et al. Occurrence of Pepper Mild Mottle Virus (PMMoV) in groundwater from a karst aquifer system in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Food Environ Virol, 2017, 9(4): 487-497. |

| [27] |

Lim ES, Zhou YJ, Zhao GY, et al. Early life dynamics of the human gut virome and bacterial microbiome in infants. Nat Med, 2015, 21(10): 1228-1234. |

| [28] |

Maqsood R, Rodgers R, Rodriguez C, et al. Discordant transmission of bacteria and viruses from mothers to babies at birth. Microbiome, 2019, 7: 156. |

| [29] |

Liang GX, Zhao CY, Zhang HJ, et al. The stepwise assembly of the neonatal virome is modulated by breastfeeding. Nature, 2020, 581(7809): 470-474. |

| [30] |

Shkoporov AN, Clooney AG, Sutton TDS, et al. The human gut virome is highly diverse, stable, andindividual specific. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 26(4): 527-541. |

| [31] |

Graham EB, Paez-Espino D, Brislawn C, et al. Untapped viral diversity in global soil metagenomes. bioRxiv, 2019, 583997. |

| [32] |

Segobola J, Adriaenssens E, Tsekoa T, et al. Exploring viral diversity in a unique south african soil habitat. Sci Rep, 2018, 8: 111. |

| [33] |

Adriaenssens EM, Kramer R, Van Goethem MW, et al. Environmental drivers of viral community composition in Antarctic soils identified by viromics. Microbiome, 2017, 5: 83. |

| [34] |

Thurber RLV, Barott KL, Hall D, et al. Metagenomic analysis indicates that stressors induce production of herpes-like viruses in the coral Porites compressa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(47): 18413-18418. |

| [35] |

Legoff J, Resche-Rigon M, Bouquet J, et al. The eukaryotic gut virome in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: new clues in enteric graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med, 2017, 23(9): 1080-1085. |

| [36] |

Wilhelm SW, Weinbauer MG, Suttle CA, et al. Filtration-based methods for the collection of viral concentrates from large water samples. Manual of Aquatic Viral Ecology. Advancing the Science for Limnology and Oceanography, 2010, 110-117. |

| [37] |

Lawrence JE, Steward GF. Purification of viruses by centrifugation. Manual of Aquatic Viral Ecology. Advancing the Science for Limnology and Oceanography, 2010, 166-181. |

| [38] |

Cao JB, Zhang YQ, Dai M, et al. Profiling of human gut virome with oxford nanopore technology. Med Microecol, 2020, 4: 100012. |

| [39] |

Nasukawa T, Uchiyama J, Taharaguchi S, et al. Virus purification by CsCl density gradient using general centrifugation. Arch Virol, 2017, 162(11): 3523-3528. |

| [40] |

Zhu BT, Clifford DA, Chellam S. Virus removal by iron coagulation-microfiltration. Water Res, 2005, 39(20): 5153-5161. |

| [41] |

Chang SL, Stevenson RE, Bryant AR, et al. Removal of Coxsackie and bacterial viruses in water by flocculation. Ⅱ. Removal of Coxsackie and bacterial viruses and the native bacteria in raw Ohio River water by flocculation with aluminum sulfate and ferric chloride. Am J Public Health, 1958, 48(2): 159-169. |

| [42] |

Johnson JH, Fields JE, Darlington WA. Removing viruses from water by polyelectrolytes. Nature, 1967, 213(5077): 665-667. |

| [43] |

John SG, Mendez CB, Deng L, et al. A simple and efficient method for concentration of ocean viruses by chemical flocculation. Environ Microbiol Rep, 2011, 3(2): 195-202. |

| [44] |

Bellas CM, Anesio AM, Barker G. Analysis of virus genomes from glacial environments reveals novel virus groups with unusual host interactions. Front Microbiol, 2015, 6: 656. |

| [45] |

Poulos BT, John SG, Sullivan MB. Iron chloride flocculation of bacteriophages from seawater. Methods Mol Biol, 2018, 1681: 49-57. |

| [46] |

Lewis GD, Metcalf TG. Polyethylene glycol precipitation for recovery of pathogenic viruses, including hepatitis A virus and human rotavirus, from oyster, water, and sediment samples. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1988, 54(8): 1983-1988. |

| [47] |

Kleiner M, Hooper LV, Duerkop BA. Evaluation of methods to purify virus-like particles for metagenomic sequencing of intestinal viromes. BMC Genomics, 2015, 16(1): 7. |

| [48] |

Göller PC, Haro-Moreno JM, Rodriguez-Valera F, et al. Uncovering a hidden diversity: optimized protocols for the extraction of dsDNA bacteriophages from soil. Microbiome, 2020, 8: 17. |

| [49] |

Trubl G, Jang HB, Roux S, et al. Soil viruses are underexplored players in ecosystem carbon processing. mSystems, 2018, 3(5): e00076-18. |

| [50] |

Trubl G, Solonenko N, Chittick L, et al. Optimization of viral resuspension methods for carbon-rich soils along a permafrost thaw gradient. Peer J, 2016, 4: e1999. |

| [51] |

Mirzaei MK, Xue JL, Costa R, et al. Challenges of studying the human virome-relevant emerging technologies. Trends Microbiol, 2020. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2020.05.021 |

| [52] |

Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J, 2011, 17: 3. |

| [53] |

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 2014, 30(15): 2114-2120. |

| [54] |

Chen SF, Zhou YQ, Chen YR, et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics, 2018, 34(17): i884-i890. |

| [55] |

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods, 2012, 9(4): 357-359. |

| [56] |

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol, 1990, 215(3): 403-410. |

| [57] |

Li ZY, Chen YX, Mu DS, et al. Comparison of the two major classes of assembly algorithms: overlap-layout-consensus and de-bruijn-graph. Brief Funct Genomics, 2012, 11(1): 25-37. |

| [58] |

Chevreux B, Wetter T, Suhai S. Genome sequence assembly using trace signals and additional sequence information. J Computer Sci Syst Biol, 1999, 99: 45-56. |

| [59] |

Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res, 2017, 27(5): 722-736. |

| [60] |

Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, et al. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome research, 2009, 19(6): 1117-1123. |

| [61] |

Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, et al. IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics, 2012, 28(11): 1420-1428. |

| [62] |

Luo RB, Liu BH, Xie YL, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience, 2012, 1(1): 18. |

| [63] |

Li DH, Liu CM, Luo RB, et al. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics, 2015, 31(10): 1674-1676. |

| [64] |

Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, et al. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res, 2017, 27(5): 824-834. |

| [65] |

Berlin K, Koren S, Chin CS, et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat Biotechnol, 2015, 33(6): 623-630. |

| [66] |

Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol, 2009, 10(3): R25. |

| [67] |

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 2009, 25(14): 1754-1760. |

| [68] |

Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics, 2018, 34(18): 3094-3100. |

| [69] |

Mistry J, Finn RD, Eddy SR, et al. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(12): e121. |

| [70] |

Van Der Auwera S, Bulla I, Ziller M, et al. ClassyFlu: classification of influenza a viruses with discriminatively trained profile-HMMs. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(1): e84558. |

| [71] |

Roux S, Enault F, Hurwitz BL, et al. VirSorter: mining viral signal from microbial genomic data. PeerJ, 2015, 3: e985. |

| [72] |

Norling M, Karlsson-Lindsjö OE, Gourlé H, et al. MetLab: an in silico experimental design, simulation and analysis tool for viral metagenomics studies. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(8): e0160334. |

| [73] |

Rosen GL, Reichenberger ER, Rosenfeld AM. NBC: the naive bayes classification tool webserver for taxonomic classification of metagenomic reads. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(1): 127-129. |

| [74] |

Ren J, Ahlgren NA, Lu YY, et al. VirFinder: a novel k-mer based tool for identifying viral sequences from assembled metagenomic data. Microbiome, 2017, 5: 69. |

| [75] |

Ren J, Song K, Deng C, et al. Identifying viruses from metagenomic data using deep learning. Quantitat Biol, 2020, 8(1): 64-77. |

| [76] |

Tampuu A, Bzhalava Z, Dillner J, et al. ViraMiner: deep learning on raw DNA sequences for identifying viral genomes in human samples. PLoS ONE, 2019, 14(9): e0222271. |

| [77] |

Auslander N, Gussow AB, Benler S, et al. Seeker: Alignment-free identification of bacteriophage genomes by deep learning. bioRxiv, 2020. DOI:10.1101/2020.04.04.025783 |

| [78] |

Stano M, Beke G, Klucar L. viruSITE-integrated database for viral genomics. Database (Oxford), 2016, 2016: baw162. |

| [79] |

Goodacre N, Aljanahi A, Nandakumar S, et al. AReference Viral Database (RVDB) to enhance bioinformatics analysis of high-throughput sequencing for novel virus detection. mSphere, 2018, 3(2): e00069-18. |

| [80] |

Pickett BE, Sadat EL, Zhang Y, et al. ViPR: an open bioinformatics database and analysis resource for virology research. Nucleic acids research, 2012, 40(D1): D593-D598. |

| [81] |

Liechti R, Gleizes A, Kuznetsov D, et al. OpenFluDB, a database for human and animal influenza virus. Database (Oxford), 2010, 2010: baq004. |

| [82] |

Zhang Y, Aevermann BD, Anderson TK, et al. Influenza research database: an integrated bioinformatics resource for influenza virus research. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017, 45(D1): D466-D474. |

| [83] |

Kamdar MR, Dumontier M. An Ebola virus-centered knowledge base. Database (Oxford), 2015, 2015: bav049. |

| [84] |

Hayer J, Jadeau F, Deléage G, et al. HBVdb: a knowledge database for Hepatitis B Virus. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(D1): D566-D570. |

| [85] |

Whittaker RH. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon, 1972, 21(2/3): 213-251. |

| [86] |

Chao A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand J Stat, 1984, 11(4): 265-270. |

| [87] |

Chao A, Lee SM. Estimating the number of classes via sample coverage. J Am Stat Assoc, 1992, 87(417): 210-217. |

| [88] |

Whittaker RH. Vegetation of the siskiyou mountains, oregon and California. Ecol Monogr, 1960, 30(3): 279-338. |

| [89] |

Liu YX, Qin Y, Guo XX, et al. Methods and applications for microbiome data analysis. Hereditas (Beijing), 2019, 41(9): 845-862 (in Chinese). 刘永鑫, 秦媛, 郭晓璇, 等. 微生物组数据分析方法与应用. 遗传, 2019, 41(9): 845-862. |

| [90] |

Shean RC, Makhsous N, Stoddard GD, et al. VAPiD: a lightweight cross-platform viral annotation pipeline and identification tool to facilitate virus genome submissions to NCBI GenBank. BMC Bioinformatics, 2019, 20: 48. |

| [91] |

Wang SL, Sundaram JP, Spiro D. VIGOR, an annotation program for small viral genomes. BMC Bioinformatics, 2010, 11: 451. |

| [92] |

Zhang KY, Gao YZ, Du MZ, et al. Vgas: a viral genome annotation system. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 184. |

| [93] |

González-Tortuero E, Sutton TDS, Velayudhan V, et al. VIGA: a sensitive, precise and automatic de novo viral genome annotator. bioRxiv, 2018, 277509. |

| [94] |

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol, 2018, 35(6): 1547-1549. |

| [95] |

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol, 2009, 26(7): 1641-1650. |

| [96] |

Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol, 2015, 32(1): 268-274. |

| [97] |

Yu GC. Using ggtree to visualize data on tree-like structures. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics, 2020, 69(1): e96. |

| [98] |

Asnicar F, Weingart G, Tickle TL, et al. Compact graphical representation of phylogenetic data and metadata with GraPhlAn. PeerJ, 2015, 3: e1029. |

| [99] |

Page RDM. Visualizing phylogenetic trees using TreeView. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics, 2003(1): 6.2.1-6.2.15. |

| [100] |

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019, 47(W1): W256-W259. |

| [101] |

Džunková M, D'Auria G, Moya A. Direct sequencing of human gut virome fractions obtained by flow cytometry. Front Microbiol, 2015, 6: 955. |

| [102] |

Castelán-Sánchez HG, Lopéz-Rosas I, García-Suastegui WA, et al. Extremophile deep-sea viral communities from hydrothermal vents: Structural and functional analysis. Mar Genomics, 2019, 46: 16-28. |

| [103] |

Fancello L, Raoult D, Desnues C. Computational tools for viral metagenomics and their application in clinical research. Virology, 2012, 434(2): 162-174. |

2020, Vol. 36

2020, Vol. 36