胸腺类器官培养及应用进展

欧越

,

周佩佩

,

王娟

,

刘翔

,

刘莉

生物工程学报  2021, Vol. 37 2021, Vol. 37 Issue (11): 3945-3960 Issue (11): 3945-3960

|

胸腺(Thymus) 是人类重要的中枢免疫器官,也是T细胞发育成熟和中央免疫耐受建立的场所。造血干细胞(Hematopoietic stem cells,HSCs) 在骨髓(Bone marrow,BM) 中分化为共同淋巴祖细胞(Common lymphoid progenitors,CLPs),CLPs通过血液循环进入胸腺,经历TCR-β选择、阴性选择(Negative selection) 和阳性选择(Positive selection) 后分化为具有免疫活性的T细胞[1-2]。但是胸腺非常脆弱,衰老、病毒感染、放化疗和骨髓移植等都可能对其造成损害,导致机体免疫自稳功能紊乱并伴发自身免疫性疾病。因此,研究胸腺损伤的病理机制并开发促进机体免疫系统恢复的有效策略,对于肿瘤靶向治疗、提高老龄人口健康水平以及缓解原发性和继发性免疫缺陷病都具有重要意义[3]。

为了促进T细胞在体外分化,可以采用拟胚体(Embryoid bodies,EBs) 分化法或将诱导多能干细胞(Induced pluripotent stem cells,iPSCs) 与小鼠胸腺基质细胞共培养[4-6],但生成的CD4+和CD8+单阳性(Single positive,SP) T细胞数量极少。新兴的类器官(Organoid) 技术很有可能解决这一难题。类器官是器官祖细胞或干细胞在体外经3D培养形成的器官特异性细胞集合,它们能够以与体内相似的方式,通过空间限制性的系别分化和细胞分序(Cell sorting out) 实现自组装(Self-organization)[7-8]。2000年,Poznansky等[9]首次报道了利用人CD34+或CD133+造血祖细胞培养胸腺类器官的方案,正式开启了胸腺类器官研究的大门。目前为止,胸腺类器官的培养起始细胞主要来源于成体脐带血(Cord blood,CB) 和BM中的造血干祖细胞(hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells,HSPCs)[9-10],目前尚无利用胸腺肿瘤组织或细胞系建立胸腺相关肿瘤类器官的报道。

构建胸腺类器官[10]的关键在于模拟胸腺基质微环境并增加T细胞的输出,这是EBs分化法等无法实现的。胸腺类器官不仅能够长期传代培养,而且其所产生的T细胞具有良好的遗传稳定性,在模拟器官组织的发生过程及生理病理状态方面优势突出。本文介绍了胸腺类器官目前报道的构建方法,总结了其培养条件;并根据是否使用支架将构建方法分为两大类,详细介绍了常用的支架(包括CellFoam[9]、Collagen Sponge[11]和小鼠胸腺脱细胞支架[12-13]等),并根据笔者实验室胸腺类器官的培养经验展望了胸腺类器官在基础研究以及临床诊疗方面的应用前景。

1 胸腺类器官组成部分 1.1 胸腺基质细胞(Thymic stromal cells, TSCs)或功能相近的滋养细胞 1.1.1 TSCs胸腺微环境主要由TSCs和细胞外基质(Extracellular matrix, ECM) 组成。TSCs包括胸腺上皮细胞(Thymic epithelial cells,TECs)、胸腺成纤维细胞(Thymic fibroblast cells,TFCs) 以及胸腺树突状细胞(Thymic dendritic cells,TDCs) 等,它们决定了胸腺细胞分化过程中的MHC限制性、抗原受体的表达以及T细胞功能亚群的形成[14-17]。其中TECs的功能最为重要:TECs排列成开放的网状结构,以便最大限度地接触胸腺中的其他细胞[14];TECs能够吸引BM来源的CLPs归巢,同时分泌白介素-7 (Interleukin-7,IL-7)、转化生长因子-β (Transforming growth factor-β,TGF-β) 等细胞因子和胸腺素,确保T细胞有序地迁移并分化成熟[15-17]。

培养胸腺类器官直接使用小鼠[12]或者人[16]来源的TSCs。由于CLPs在胸腺内通过Notch1结合皮质胸腺上皮细胞(Cortical thymic epithelial cells,cTECs) 和髓质胸腺上皮细胞(Medullary thymic epithelial cells,mTECs) 表面的DLL1或DLL4配体完成T细胞的定向分化,因此也可以用转导DLL1或DLL4基因的小鼠骨髓基质细胞作为胸腺类器官的滋养细胞。2002年,Schmitt等[18]首次向OP9细胞中转染DLL1基因并建立OP9-DL1单层培养体系,支持小鼠或人多能干细胞(Human pluripotent stem cells,HSPCs) 在体外分化为T细胞。2017年,Seet等[10]将人DLL1基因转导到MS5细胞中,获得人工胸腺类器官(Artificial thymic organoids,ATOs) 的滋养细胞MS5-hDLL1。Seet等[10]建立的ATOs在T细胞定向分化的效率与OP9-DL1单层培养体系没有明显差异,但CD4+CD8+双阳性(Double positive,DP) 和CD3+TCR-αβ+ SP T细胞的生成量明显超过后者。如果将OP9-DL1二维培养系统改为三维培养系统,也能增强OP9-DL1细胞支持T细胞体外分化的能力。2018年,Vizcardo等[17]将OP9-DL1细胞与iPSCs、小鼠胚胎胸腺碎片一起进行悬滴培养,获得iPSC来源的胸腺迁移物(iPSC-derived thymic emigrants,iTEs)。将iTEs产生的T细胞由尾静脉注入黑色素瘤模型鼠体内,T细胞能够大量扩增、形成免疫记忆并抑制肿瘤生长。

为了找到更合适的滋养细胞,Montel-Hagen等[19]在培养多能干细胞-ATOs (Pluripotent stem cell-ATOs,PSC-ATOs) 时,比较了MS5-hDLL4细胞和MS5-hDLL1细胞的作用。使用MS5-hDLL4作为滋养细胞建立的PSC-ATOs培养7周后产生的CD3+TCRαβ+CD8+SP T细胞数量高达1.5×106个,明显超过以MS5-hDLL1作为滋养细胞的PSC-ATOs。Montel-Hagen等[20]使用转导小鼠DLL4基因的MS5-mDLL4细胞和单个HSC就能顺利构建小鼠胸腺类器官(Murine artificial thymic organoids,M-ATOs),在培养6-7周时输出的细胞总量高达2×106-10×106个,包括TCRβ+、多克隆CD4SP、多克隆CD8SP和Foxp3+CD4+CD25+等成熟胸腺细胞。Bosticardo等[21]使用MS5-hDLL4细胞,也成功建立了先天性免疫缺陷病DiGeorge综合征(DiGeorge syndrome,DGS) 的ATOs模型。

综上所述,转导人或小鼠DLL4基因的滋养细胞在促进人或小鼠胸腺类器官产生CD8+SP T细胞方面,可能更具有优势。根据我们利用OP9-DL1细胞培养M-ATOs的经验来看,产生的CD8+SP T细胞数量确实低于相关文献报道[20]。同时,经过基因编辑的滋养细胞容易出现目的基因脱靶问题;经过多次传代后,滋养细胞逐渐老化,支持T细胞体外发育的能力明显降低。如何构建稳定性高的滋养细胞系,也是培养胸腺类器官必须考虑的问题。

1.1.2 皮肤成纤维细胞和角质形成细胞FoxN1属于叉头框转录因子家族成员,主要表达于皮肤成纤维细胞、角质形成细胞和TECs中。胚胎期胸腺只有在FoxN1正常表达的情况下才能产生mTECs和cTECs,并完成进一步的增殖和分化[20]。此外,TECs和皮肤成纤维细胞、角质形成细胞都能在角质细胞生长因子(Keratinocyte growth factor,KGF) 的作用下增殖,皮肤角质层的部分角蛋白也与mTECs的赫氏小体(Hassall’s corpuscle) 相同。有鉴于此,研究人员采用皮肤成纤维细胞、角质形成细胞替代TECs建立胸腺类器官,所产生的T细胞在体外和体内均表现出与正常初始T细胞(Naive T cell,Tn) 高度相似的表型和功能(图 1)[14, 22]。同时由于人的皮肤样本容易获取且来源充足,利用其培养胸腺类器官,可以避免不同种属生物的免疫排斥。

|

| 图 1 三维皮肤培养物的结构[14] Fig. 1 Structure of 3-dimensional skin cell cultures. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of the CellFoam 3-dimensional matrix. Image courtesy of Cytomatrix LLC. The morphologies of (B) fibroblasts stained with vimentin antibody and (C) keratinocytes stained with antibodies to cytokeratins when these cells were grown alone on matrices. (D) When grown together, keratinocytes (orange) and fibroblasts (green) occupied distinct sites on the matrices. (E) DCs, identified by intense staining with HLA-DR antibodies, were observed only if bone marrow progenitor cells were added to the matrices. (F) DCs were often found adherent to the surface of vimentin+ fibroblasts. Scale bar=100 μm[14]. |

| |

TECs如果与辐照灭活的3T3细胞或其他间充质饲养细胞进行二维培养,就会表达终末分化、衰老的上皮细胞标记物[23]。只有处于胸腺特有的空间结构中,调控TECs增殖和生理功能的基因(如FoxN1、DLL-4、TBATA、CLL-22) 才能正常表达[22-23]。此外,类器官的自组织特性可能导致其形成异常的组织结构,使用支架可以有效降低这一风险。

理想的支架应使用非致炎性原料,植入宿主体内不会引起免疫排斥反应,被宿主分解后也不会释放有毒物质。生物支架促进组织再生的作用与支架的成分、空间结构以及释放细胞因子的能力密不可分。研究人员可以通过灌注法对动物的组织器官进行脱细胞处理[16, 18],也可以选择多孔钽金属支架[24-25],或者根据T细胞分化所需的培养环境[26]利用胶原自行配制[11, 23, 27]。

1.3 贴近胸腺ECM的培养环境胸腺ECM是由胸腺细胞将弹性纤维、胶原蛋白和蛋白聚糖等分泌到细胞外、细胞表面以及细胞间所形成的大分子网络结构。ECM不仅是控制特定胸腺生理活动的微环境[26],也是趋化因子和生长因子的储存库。ECM在发挥支撑作用的同时,还能动态调节细胞功能[23],指导胸腺细胞在不同区域间迁移。脱细胞支架保留的ECM主要成分和超微结构越完整,越有益于再细胞化(Recellularization)。Pinto等[28]使用非织造材料Jettex (ORSA)、凝血酶和纤维蛋白原开发了一种3D人工基质,并在其内部包埋人类皮肤来源的真皮成纤维细胞以产生ECM。将CD80loAire-mTECs接种到基质上,能够分化为CD80hiAire+mTECs。虽然该方法显著提高了mTECs的活性,但耗时较长,且不适用于cTECs。如果采取该方法提供mTECs和ECM,再培养胸腺类器官,恐怕无法满足临床需求。

ECM在生物进化过程中高度保守,不同种属间相同组织内ECM差异较小,经脱细胞技术去除引起免疫排斥反应的细胞成分和抗原后就能安全地用于异种异体移植。因此可以从小鼠等哺乳动物的胸腺中直接获取ECM,从而避免收集人胸腺样本的困难和伦理问题。Fan等和Tajima等[12-13]将小鼠胸腺进行脱细胞处理时,首先要通过冻融循环来诱导细胞内冰晶的形成,导致细胞膜破裂;然后用洗涤剂诱导细胞裂解,最后清洗细胞碎片。反复冻融能更好地增加组织和细胞的通透性,避免脱细胞试剂的毒性带来移植后的免疫排斥反应。

虽然冻融法得到的胸腺脱细胞支架保留了大部分ECM,但操作过程需要消耗大量时间和精力。考虑到胸腺缺乏为整个器官供血的主要动脉,无法像肝、肾等器官通过血管灌注清洗液实现高效的脱细胞,Campinoti等[16]改进了处理方法。他们首先打开一条颈动脉,同时关闭下游所有其他到达胸腺的动脉,然后向该颈动脉中依次灌注MilliQ-H2O、洗涤剂和DNase-Ⅰ溶液,在提高工作效率的同时最大限度地保留了胸腺内的微观构造和ECM。DNase-Ⅰ溶液有助于分解ECM中残留的大量原组织中的DNA,降低了宿主产生免疫排斥的可能性。

2 胸腺类器官培养系统及发展现状 2.1 类器官支架材料常用的胸腺类器官支架可以分为胶原支架[11, 23, 27]、胸腺脱细胞支架[16, 18]和钽金属支架[24-25]三大类,且各具特点:胶原支架具有生物可降解性[29],且能按照实验需求调整孔隙直径和密度;脱细胞支架含有哺乳动物胸腺来源的ECM、生长因子和细胞因子,支持T细胞增殖分化的成分最丰富;钽支架坚固耐用,整体容积孔隙率高。无论使用什么方法构建支架,这些支架都必须具备适宜的机械强度和柔韧性、促进胸腺细胞附着的多孔结构以及良好的生物相容性,且易于批量生产。现有胸腺类器官支架的优缺点比较见表 1。

| Scaffolds | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| CellFoam matrix | The open-pore structure allows cells to infiltrate and integrate into the surrounding engraftment site | The matrix is unable to be degraded by the body | [9, 29] |

| Collagen sponge | Insoluble collagen constitutes the main source of the matrix. It is primarily used for 3D or high-density cell culture in vitro | Scientists haven’t figured out why the attraction and accumulation of cells in the transplant was substantially influenced by the supporting material, but some deduced it may relate to subtle differences in biocompatibility or in the capacity to incorporate TEL-2-LTα and DCs for renal subcapsular transplantation. The pore size and porosity of the material as well as the size of the whole scaffold used for transplantation, may also be crucial features | [11] |

| Poly ε-caprolactone | It is a biocompatible structure with a high surface area/volume ratio due to its high porosity, thus being an ideal scaffold. Secondly, the bimodal population of pores is strongly desired to assure efficient nutrient transport and waste removal within the scaffold. Thirdly, cell growth and migration are also favored thanks to a higher surface/volume ratio | However, the maturation process does not lead to the production of fully mature single-positive T cells. This suggests that additional factors or molecular manipulations should be used to recapitulate a TEC-like surrogate environment | [30] |

| 3D collagen type Ⅰ scaffolds | Collagen type Ⅰ scaffolds possess essential factors that could be exploited and further implemented for thymic tissue engineering, such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical properties to ensure cell penetration and scaffold vascularization | Scaffolds degradation was already visible and detectable 2 weeks after in vivo implantation, obstructing any functional studies and most importantly weakening iOCT4 TEC organoids’ ability to sustain de novo thymopoiesis | [32] |

| Decellularized thymus scaffolds | The 3-D ECM environment of the decellularized thymus offered a suitable and essential niche for the long-term survival of adult TECs | The manufacturing process was rather complicated in detail | [12-13, 16, 33] |

CellFoam matrix (Cytomatrix) 是一种由钽金属在高温下以薄层的形式均匀沉积到碳骨架上形成的多孔材料,因其生物相容性出色而广泛应用于骨骼修复[23]。CellFoam的纳米结构为细胞-细胞、细胞-支架提供较大的相互作用表面积,既维持了细胞之间的信息交流和物质交换,又能对细胞的充分附着和顺利迁移产生良性刺激。2000年,Poznansky等[9]在CellFoam表面共培养C57BL/6J小鼠胸腺碎片与CD34+或AC133+祖细胞,首次培养出胸腺类器官,并产生了大量T细胞受体重排删除环(T-cell receptor excision circles,TRECs) 表达水平较高的CD3+ T细胞。TRECs是T细胞受体基因重排过程中删除的DNA环,可作为Tn的标记。TRECs高表达说明胸腺类器官能够稳定输出Tn。

2003年,Marshall等[25]采用类似的方法,在Cytomatrix®上共培养sjlb6 (Ly5.21) 小鼠胸腺碎片与造血祖细胞,使造血祖细胞顺利分化为CD4+和CD8+SP T细胞。2005年,Clark等[14]在CellFoam上共培养人类成纤维细胞、角质形成细胞和AC133+前体细胞。该类器官产生的T细胞对供体MHC具有耐受性,能顺利完成阳性选择和阴性选择,也能表达Aire、FoxN1和Hoxa3等基因编码的转录因子和一组自身抗原(见图 1)。由于钽金属支架方便获取,在力学性能、促组织内生性上优势突出,早期的胸腺类器官研究多以其作为支架材料,但在研究过程中也暴露出一系列问题。首先,钽金属熔点超过3000 ℃,即使依靠3D打印也很难选择合适的粉体性能、铺粉质量和打印精度;其次,金属支架不包含生物信号和生长因子,在刺激细胞分化方面明显存在缺陷;最后,钽金属支架不能被生物体降解。如果想要通过植入胸腺类器官重建宿主免疫系统,CellFoam并不是最理想的原料。因此,后期的胸腺类器官研究多使用细胞支架和胶原支架,以便于降低制作的难度和添加生物活性成分。

2.1.2 胶原海绵(Collagen sponge,CS)CS是牛跟腱经冷冻干燥法制备的不溶性胶原,延展性和生物降解性良好。CS能利用其海绵结构的毛细作用迅速吸附细胞、刺激细胞分裂和迁移(Cell migration),因此常用于体外3D培养或高密度细胞培养。2004年,Suematsu等[11]将TEL-2-LTα细胞和活化的DC滴在CS上,通过挤压使支架吸收细胞,进而培养淋巴类器官。TEL-2-LTα细胞是小鼠的胸腺基质细胞,能够表达淋巴细胞B受体(Lymphotoxin β receptor,LTβR) 和血管细胞黏附分子(Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1,VCAM-1)。将淋巴类器官移植到严重联合免疫缺陷(Severe combined immunodeficiency disease,SCID) 小鼠的肾包膜下,静脉注射抗原后小鼠可以产生抗原特异性抗体。淋巴细胞类器官内不仅有B细胞簇和T细胞簇,还形成了高内皮细胞微静脉(High endothelial venule, HEV)、生发中心和滤泡DC网络。淋巴类器官有助于分析次级淋巴器官发育所需的细胞-细胞相互作用和诱导适应性免疫反应,并可能用于治疗免疫缺陷(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 将类器官移植到肾包膜下,胶原支架中包埋的TEL-2-LTα细胞以及活化的树突状细胞加速了淋巴细胞向移植物中的聚集[11] Fig. 2 Inclusion of activated DCs in collagenous scaffold in which TEL-2-LTα cells are embedded for renal subcapsular transplantation accelerates lymphocyte accumulation in the transplants. Two types of transplants were prepared. TEL-2-LTα cells embedded in collagenous scaffolds were transplanted under the capsule of left kidney in mice (A), and TEL-2-LTα plus activated DCs embedded in collagenous scaffolds were transplanted to the right kidney (B). Three weeks later, transplants were collected and 5-mm-thick frozen sections were immunostained. T cells are stained in red with anti-Thy1.2 monoclonal antibody (mAb), and B cells are stained in green with anti-B220 mAb[11]. |

| |

一方面,CS能激活和诱导各种生长因子,保证成纤维细胞活性和胶原纤维正常产生及排列;另一方面,CS能够促进毛细血管的形成,有利于组织再生以及新生组织与胶原材料融合。这两个特点不仅使CS成为了创面修复的理想材料,还赋予其引导HEV再生的能力,这是其他材料所难以企及的[11]。如果想要类器官在体内移植后形成血管并获得宿主的持续供血,可以考虑用CS作为支架。

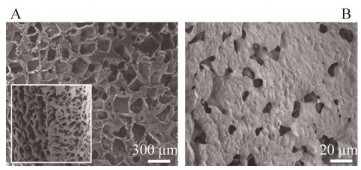

2.1.3 聚ε-己内酯(poly ε-caprolactone,PCL)PCL是一种可以被人体彻底降解为H2O和CO2的高分子聚合物,理化性质稳定。连通性良好的微孔保障了细胞在PCL支架内高效吸收养分并清除废物,高比表面积[30]则有助于细胞粘附生长和迁移。2013年,Palamaro等[30]在大鼠尾胶原Ⅰ溶液中孵育PCL支架,用于角质形成细胞、成纤维细胞以及CD34+HSCs共培养(图 3)。该类器官产生的T细胞中,TAL1基因表达下调,SPIB基因表达上调,与正常人T细胞系定型过程一致。此外,还检测到T细胞系特异性基因PTCRA、RAG1/2的表达,证明细胞具有产生T细胞受体库所必需的重组活性[30]。Palamaro等[30]据此推测,在没有胸腺细胞的情况下,皮肤角质形成细胞有可能取代TECs支持T细胞的分化。

|

| 图 3 对PCL支架形态的定性和定量研究[30] Fig. 3 Qualitative and quantitative investigations of PCL scaffold morphology. Scanning electron micrographs of macropores (cross-section in the square) (A) and micropores (B). Cumulative distribution of pore surface and volume estimated by 2D-IA and MIP techniques, respectively. Scale bar: 20 μm and 300 μm[30]. |

| |

利用胶原蛋白组和纤维制成的胶原多孔生物基质在化学性质和形态特征上非常接近软组织,常作为生物材料用于临床治疗[31]。2019年,Bortolomai等[32]将3D Ⅰ型胶原支架与3% 1, 4-丁二醇二缩水甘油醚(BDDGE) 交联,再接种经过基因修饰的TECs。胸腺类器官交联支架的一侧为排列整齐的多孔结构,类似于胸腺髓质;另一侧为孔隙较少但更坚硬的纤维结构,类似于胸腺皮质。支架的机械强度、扩散率和渗透率也受孔径均匀性的影响。孔径过小则细胞迁移的不完全,甚至在支架周缘形成包囊,妨碍物质交换。而孔径过大则会降低支架的比表面积,阻碍细胞的粘附和增殖分化。细胞在小孔径支架中初始增殖率较高,但分化明显受限。BDDGE交联Ⅰ型胶原支架的孔径略大于天然胸腺,在高效完成物质交换的同时保证了良好的细胞透性和支架定植能力(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 模拟胸腺超微结构的三维支架的产生[32] Fig. 4 Generation of collagen-based scaffolds mimicking the thymic ultrastructure. Electron microscopy images showing the ultrastructure of a murine native thymus and collagen type Ⅰ scaffolds with two different percentages, 3% (Coll3_1C) and 5% (Coll5_1C), of the crosslinker BDDGE and one cortical layer. Our scaffolds recapitulate the medullary and cortical features of a normal thymus. Scale bar: 200 μm for medulla and cortex magnification; 10 mm for overview magnification[32]. |

| |

该支架的缺陷在于,BDDGE本身具有细胞毒性,未完全反应或残留的BDDGE移植后可能引起无菌性炎症。另一方面,环氧化合物交联的生物组织在植入生物体内后容易发生钙化,导致移植物机械强度下降,甚至缩短使用寿命。

2.1.5 经过脱细胞处理的支架通过物理方法(如机械搅拌和快速冷冻)、化学方法(如非离子洗涤剂和SDS清洗)和酶法(如胰蛋白酶和DNase),诱导细胞裂解、去除细胞碎片后再进行蛋白质基质复性,可以得到保留内部网状结构、ECM和T细胞分化因子的胸腺脱细胞支架。2015年,Fan等和Tajima[12-13]通过冻融循环诱导B6鼠胸腺细胞内形成冰晶,然后用洗涤剂诱导细胞裂解并清除细胞碎片,获得胸腺脱细胞支架。他们将B6鼠和CBA/J小鼠的TSCs混合,再将B6鼠的Lin-细胞和TSCs混合物注射到脱细胞胸腺支架中。获得的胸腺类器官植入到裸鼠体内可以有效地促进CLPs归巢并分化为多种功能性T细胞(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 利用脱细胞胸腺支架重建胸腺类器官[12] Fig. 5 Reconstruction of thymus organoids from decellularized thymus scaffolds. Light microscopic images of a decellularized thymus scaffold (left panel) and a reconstructed thymus organoid (with CD45- thymic stromal cells and bone marrow cells of Lin- population at 1:1 ratio) cultured overnight in vitro (right panel)[12]. |

| |

2017年,Hun等[33]使用CHAPSO清除成年B6小鼠的胸腺细胞,将E14.5胎鼠的TECs和TFCs混合后接种到脱细胞支架上。CHAPSO在去除细胞的同时,对支架中的胶原、主要结构蛋白及超微结构均无明显影响。裸鼠移植胸腺类器官后,外周血(Peripheral blood,PB) 和脾脏中也检测到大量的Tn和成熟T细胞,表明移植小鼠得到了免疫重建。2020年,Campinoti等[16]去除了大鼠胸腺中的所有细胞仅保留结构支架,然后向支架中注入人的TECs及间质细胞。仅5 d后,胸腺类器官的体积就接近九周胎儿的胸腺;植入小鼠体内后,超过75%的胸腺类器官能够支持人类T细胞的发育。

2.2 未使用支架的胸腺类器官无支架培养的原理是在体外利用细胞培养微环境的刺激使PSCs自发形成胸腺类器官。2017年,Seet等[10]建立了一种无血清的人类ATOs培养系统,避免了动物血清的免疫原性和免疫反应性。无血清系统的另一优势在于减少了换液的次数,保障了无支架ATOs的结构完整性。ATOs能够支持人CB、BM和PB来源的CD34+HSPCs高效完成分化、阳性选择和成熟。Seet等[10]将CD34+CD3-HSPCs和MS5-hDLL1细胞混合并离心,然后在Millicell插入式细胞培养皿(Millicell Transwell insert) 上进行气液界面培养混合细胞沉淀。ATOs中T细胞的表型变化过程很接近正常人类胸腺,并且ATOs中发育的CD3+CD8- SP和CD3+CD4- SP T细胞都能够产生细胞因子且在抗原刺激下增殖,具有完整的TCR库。

2019年,Montel-Hagen等[19]开发了一种更加高效、标准化的人类PSC-ATOs,以诱导TCR工程的PSCs分化为具有抗肿瘤活性的抗原特异性Tn。他们首先诱导人胚胎多能干细胞(Human embryonic stem cells,hESCs) 生成人胚胎中胚层祖细胞(Human embryonic mesodermal progenitors, hEMPs),将其与MS5-hDLL1/4细胞[10]培养为胚胎中胚层类器官(Embryonic mesoderm organoids,EMOs)。EMOs在造血诱导条件下可分化为ATOs。

2020年,Bosticardo等[21]参考Seet等[10]的方法,建立了DGS患者的胸腺类器官模型。同年,Montel-Hagen等[20]使用C3H/He、C57BL/6、BALB/c和FVB 4种小鼠建立M-ATOs培养系统,利用单个HSCs就足以培养M-ATOs并产生大量不同亚型和功能的小鼠T细胞。M-ATOs在第2周时即可诱导HSPCs定向分化为T细胞系,而表达非T细胞谱系标志物的细胞数量显著下降。第2-3周M开始出现未成熟的CD8 SP和CD8+CD4+ DP细胞群体,在第6周检测到调节T细胞(Regulatory T cells,Tregs),并可长期生存。M-ATOs系统能充分反映原发性胸腺的表型和转录T细胞发育状况,以及T细胞发育阶段中Notch报告基因活性的变化,有助于研究正常小鼠胸腺细胞生成的生理机制。

3 胸腺类器官的潜在应用 3.1 探索T细胞分化和发育Montel-Hagen等[19]利用ATO和PSC-ATOs探索人类T细胞正常发育和定向分化的生理机制。胎儿和成人的T细胞发育过程不同,胎儿T祖细胞来自胎肝HSCs,成人则来自BM HSCs。干细胞起源的不同在以后的淋巴细胞发育中具有不同意义,例如成人的T细胞和B细胞在分化最早期表达DNTT基因编码的末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶(Terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase,TdT),而TdT在胎儿中的表达较低。Montel-Hagen等[19]通过流式细胞术发现,利用CB HSCs建立的ATOs和产后胸腺所产生的T细胞在ISP4和DP阶段均可检测到TdT,且分别符合该阶段TCRβ和α链重排的特征;而胎儿胸腺和PSC-ATOs所产生的T细胞几乎没有TdT的表达,表明二者在T细胞发育方面具有发育相似性。此外,由于PSC-ATOs几乎不表达DNTT,导致TCRs的互补决定区3 (Complementarity determining region3,CDR3) 区域更短。这也符合T细胞和B细胞在人类胎儿发育初期CDR3区域较短后期逐渐变长的特性。

3.2 建立胸相关疾病的模型 3.2.1 原发性免疫缺陷病DGS即先天性无胸腺或发育不全,属于原发性细胞免疫缺陷病。Bosticardo等[21]使用DGS患者的CD34+细胞建立ATOs,以研究该疾病的病理机制。他们发现,胸腺细胞存活率下降和T细胞早期发育的阻滞均与AK2基因缺失有关。ATOs所产生的T细胞在分化动力学、表型等方面均符合DiGeorge综合征患者在造血功能方面的特征。ATOs系统有助于确定T细胞分化受阻的确切阶段,足以作为DGS的代表性模型。

3.2.2 胸腺肿瘤胸腺肿瘤包括来源于胸腺内分泌细胞的肿瘤-胸腺类癌和燕麦细胞癌、TECs的胸腺癌和肿瘤-胸腺瘤以及来源于胸腺淋巴细胞的霍奇金淋巴瘤等。胸腺瘤在成人前纵隔肿瘤中占30%左右[34],目前治疗胸腺瘤主要依靠手术、铂类为基础的化疗和靶向药(包括靶向c-kit受体的多激酶抑制剂伊马替尼[35]、ABL/Src激酶抑制剂达沙替尼[36]) 等。但对于晚期无法切除、切除后复发或者转移的胸腺肿瘤以及完全切除胸腺肿瘤后如何进行合理的辅助治疗,学界尚无统一的意见。

相较于细胞系、基因工程鼠(Genetically engineered mouse models,GEMMs) 和人源化异种移植鼠(Patient-derived xenografts,PDXs) 等传统模型,鼠源类器官(Mouse-derived organoids,MDOs) 和人源类器官(Patient-derived organoids,PDOs) 不但能够采用正常组织和不同癌变阶段的肿瘤组织进行培养,而且简单易操作,时间和金钱成本较低,效率较高。体外培养的PDOs能够很好地反映多种大肿瘤组织(Bulk tumor) 的生理和病理特性[37],大部分PDOs所展现的治疗反应和对应患者的初始疗效是一致的。与其他模型相比,PDOs对具有细胞毒性的药物敏感性较强,能更好地预测患者用药后可能产生的不良反应[38-39]。当前胸腺瘤类器官的研究还处于空白状态,如果构建出胸腺类器官以及胸腺瘤类器官,很有可能推动胸腺瘤靶向药在药敏试验方面的发展。

3.2.3 人类免疫缺陷病毒(Human immunodeficiency virus, HIV) 感染淋巴组织纤维化是HIV感染的主要特征之一,该症状在抗逆转录病毒治疗期间持续存在,最终阻碍患者免疫细胞运输。Samal等[40]结合胸腺类器官开发了一种骨髓-肝-胸腺-脾(BM-liver- thymus-spleen, BLTS) 人源化小鼠模型,来研究HIV感染诱导的淋巴组织纤维化造成的免疫细胞损伤。他们首先让NSG小鼠接受非致死剂量(200 rads) γ射线辐照,再将人类胎儿组织(脾脏、胸腺和肝脏) 加工成1 mm2大小的碎块,作为“三明治”移植到肾包膜下;然后向小鼠移植人类胎肝来源的CD34+HSC细胞,10周后如果能通过流式细胞术检测到人类免疫细胞,则BLTS成功建立。该模型的遗传代谢机制更接近人类,如果与猕猴模型同时用于探究HIV感染导致的淋巴组织纤维化,有望在降低研究难度和成本的同时提高准确性。

PD-1阻断剂在治疗癌症和抵抗慢性HIV感染导致的T细胞衰竭中发挥重要作用。凋亡抑制蛋白(Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins antagonist,IAP) 拮抗剂Debio 1143 (D1143) 有促进肿瘤细胞死亡的协同作用。Bobardt等[41]向人源化小鼠体内移植胸腺类器官,并构建艾滋病模型鼠,以研究D1143是否可以刺激抗人PD-1单克隆抗体(monoclonal antibody,mAb) 发挥效力,减少人源化小鼠体内的艾滋病毒载量。治疗4周后,单独应用抗PD-1 mab使PD-1+CD8+细胞数量下降了32.3%,联合应用D1143则效果更显著,使细胞减少了73%。抗PD-1 mab可将血液中的HIV载量降低94%,而D1143的加入进一步将降幅从94%提高到97%。联合用药2周后,所有组织中CD4 +细胞的艾滋病病毒载量[包括脾(71%-96.4%)、淋巴结(80%-64.3%)、肝脏(64.2%-94.4%),肺(64.3%-80.1%) 和胸腺类器官(78.2%-98.2%)] 减少5倍以上。Bobardt等[41]由此推断,联合运用D1143和PD-1阻断剂,能够有效减缓患者免疫系统受损的速度,提高患者的生存质量。

3.3 免疫治疗 3.3.1 产生肿瘤特异性T细胞纽约食管鳞状细胞癌1抗原(NY-ESO-1) 是肿瘤免疫治疗的良好候选靶标,具有引发自发性体液免疫和细胞免疫应答的功能以及限制性表达模式[19]。2017年,Seet等[10]分离出ATOs来源的CD8+SP细胞,将它们和表达CD80以及单链三聚体抗原HLA-A*02:01-B2M-NY-ESO-1157-165的人工抗原呈递细胞(Artificial antigen presenting cells,aAPCs) 共培养。Seet等[10]向K562细胞内转导HLA-A*02:01-NY-ESO-1157-165序列,再向4-6周龄的NSG小鼠皮下注射以构建荷瘤鼠。通过荷瘤鼠眼眶后静脉注射aAPCs激活的CD8+SP T细胞,同时向对照小鼠注射PBS,ATOs来源的CD8+ SP T细胞对小鼠体内的肿瘤有显著的抑制作用。

2019年,Montel-Hagen等[19]按照Seet等[10]的方法构建荷瘤鼠,再利用负载mTagBFP2荧光蛋白和1G4 (人类抗NY-ESO-1特异性TCR) 的编码序列的慢病毒载体转导hESCs,进而培养PSC- ATOs。将PSC-ATOs产生的CD8αβ+ NY-ESO-1 TCR T细胞注射到荷瘤鼠体内,明显控制了肿瘤的生长。Montel-Hagen团队还设想,如果能在体外通过基因编辑使PSCs表达靶向癌症的T细胞受体并无限扩增这些PSCs,则意味着可以利用PSC-ATOs源源不断地生成肿瘤靶向性的T细胞。但如何制造既带有抗癌受体,又不会引起患者免疫系统排斥的T细胞,也是亟需解决的问题。

3.3.2 再生医学和器官移植无免疫抑制状态(Immunosuppression-free state,IFS) 是指移植物在宿主体内保持正常生理功能和组织学特性,不受到宿主免疫系统攻击的状态,是宿主接受移植物的表现[3]。尽管目前尚未完全理解胸腺在移植物达到IFS过程中的具体作用,但在移植同种异体的器官、组织或细胞的同时植入人工胸腺,可能会促进IFS实现[42]。实体器官移植(Solid organ transplantation,SOT) 和自身免疫模型已经初步证实了将再生医学技术应用于生物工程胸腺或淋巴组织的可行性。Yamada等[43]发现,诱导受体对移植肾脏产生耐受,可能需要向受体移植供体的胸腺;如果在受体异位移植异源心脏的同时,还移植了有血管的供体胸腺小叶,移植接受者可能会对异源心脏产生长期耐受。

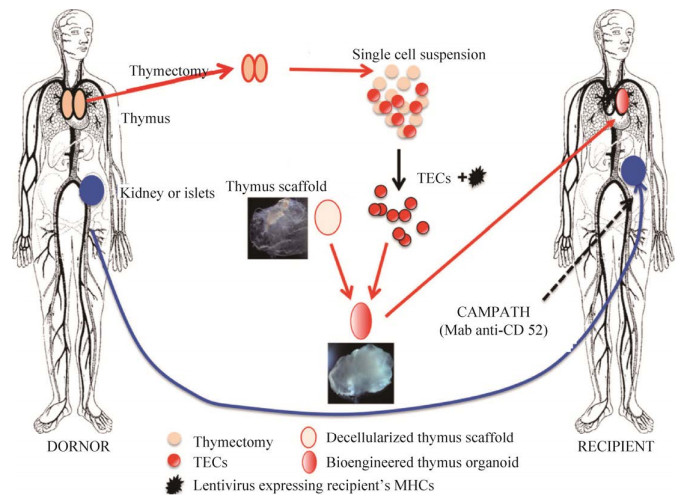

2016年,Tajima等[42]根据鼠皮肤移植实验[12-13],构想了一个可能实现IFS的方案(图 6):从遗体器官捐献者体内取出胸腺与即将移植的器官(例如肾脏或胰岛),利用胶原酶将胸腺消化成单细胞悬液(图 6)。通过FACS从胸腺富集TECs和其他胸腺间充质细胞,用慢病毒颗粒转染供体TECs使其表达受体的MHC分子[43],并用这些细胞填充脱细胞支架。支架可以利用异体甚至异种来源的胸腺制备,因为ECM的成分在进化上是高度保守的[44],通常不会成为抗原。首先给予受体淋巴细胞清除剂(例如ATG或抗CD52的Campath),再将人工胸腺植入胸腔并连接胸内动脉,以取代老年受体已经明显萎缩和退化的胸腺,或者作为年轻受体中现有胸腺的补充。胸腺类器官一旦植入供体,可能会产生一个新的Tn细胞库,在发挥适应性免疫功能的同时对供体细胞保持免疫耐受,最终实现移植物的长期生存而不需要给予患者免疫抑制药物。Campinoti等[16]也有类似的设想,虽然这些方案暂时停留在理论阶段,但也为解决器官移植后的排斥问题提供了新的解决思路。

|

| 图 6 利用脱细胞胸腺支架重建胸腺类器官[42] Fig. 6 Induction of donor-specific allograft tolerance by thymus bioengineering. Thymus gland is harvested from a cadaver donor in conjunction with the organ to be transplanted (e.g., kidney or pancreatic islets). Recipient: preconditioned with lymphocyte-depletion regimen [e.g., campath (anti-CD52) or ATG (anti-thymocyte immunoglobulin)], will receive the transplant. Donor thymic epithelial cells (TECs) will be isolated from the dissociated thymus, transduced with lentiviral particles expressing the recipient's MHC molecules, and used to reconstruct the thymus organoids with surrogate thymus scaffolds. The bioengineered thymus organoid will be transplanted into the recipient, either as an additional thymus lobe (in young patients) or as a replacement (in older patients) at the time of organ transplantation. Representative images of a decellularized thymus scaffold (mouse) and a bioengineered thymus organoid (mouse) are shown[42]. |

| |

慢性移植物抗宿主病(Chronic graft versus host disease,cGVHD) 给HSCs移植后的长期存活造成了巨大的阻碍。由于缺乏能概括临床cGVHD多器官病理的动物模型,科学家一直没有开发出cGVHD有效的治疗方法。为了解决这一问题,Lockridge等[45]向免疫缺陷小鼠移植人类胚胎造血干细胞、人类胚胎胸腺和肝脏碎片,以研究由人类免疫细胞导致的多器官纤维化病理。移植100 d后,小鼠开始出现cGVHD的症状,多器官均出现人类T细胞、B细胞和巨噬细胞的细胞浸润;肺和肝脏等部位发生纤维化;皮肤增厚,毛发脱落。疾病进展通常伴随着广泛的纤维化和胸腺类器官的退化,并且疾病的严重程度与FoxP3+胸腺细胞的频率呈负相关。Lockridge等[45]认为,人胸腺组织可能贡献具有致病潜力的T细胞,但胸腺类器官中的Tregs有助于控制致病性T细胞,这也为cGVHD的治疗提供了新策略。

4 总结与展望作为处于体内与体外实验交叉点的多功能模型,胸腺类器官重现了T细胞的发育过程,可长期保持干细胞供体的遗传特性和细胞极性,在研究T细胞体外扩增分化、胸腺生发过程和特异性细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(Cytotoxic T lymphoid cells,CTLs) 等方面有其他类器官的所无法比拟的优势。但目前胸腺类器官培养仍面临许多挑战。

4.1 添加诱导血管生成的细胞因子现有的胸腺类器官无法涵盖胸腺组织中所有细胞和细胞因子,因而无法完全重现正常胸腺的功能。例如,胸腺基质产生的血管内皮生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF) 能够有效诱导血管生成,这对新生小鼠的胸腺生长极为关键[42]。人胸腺TECs聚集体和表达VEGF的胸腺间充质可以募集出生后的人造血祖细胞,促进人造血祖细胞在NSG人源化小鼠中分化为T细胞[46]。但现有的胸腺类器官培养系统中并未加入血管生成相关的细胞因子。而生物工程类器官移植时,需要将类器官与受体的血管系统进行连接,避免因缺血导致大量细胞死亡[47]。向生物材料中添加血管生成必需的细胞因子和生长因子,促进类器官形成血管系统,可能是提高生物工程胸腺类器官植入后功能和受体存活率的有效途径。

4.2 选择更理想的移植部位大多数胸腺类器官或淋巴结类器官主要选择肾包膜下[11-12]、皮下[16]作为移植位置,近年也有报道将淋巴结作为胸腺细胞或淋巴结类器官的移植位置,呈现出肾包膜下和皮下移植所不具备的优点。人肾被膜下间隙缺乏弹性和紧密性,而淋巴结具有纤维化的网络结构和其他基质细胞,能够为移植物提供物理和营养支持。Fan等[12]发现,胸腺类器官移植到肾包膜下2-4周后,胸腺单元明显萎缩,说明该位置不能满足胸腺类器官长期生存的需要。此外,淋巴结可塑性较强,能够长期保持其生理功能。Komori等[48]将新生CBA/CAj或者C57BL/6小鼠胸腺细胞移植到裸鼠空肠淋巴结中,细胞定植后产生的移植物含有大量受体来源的CD31+内皮细胞;在每个接受胸腺细胞移植的淋巴结中,都检测到了CD105+细胞和胶原Ⅳ+细胞。CD31是血管内皮的标记物,CD105和Ⅳ型胶原是新生血管的标记物,它们的出现表明移植物在异位组织发生了广泛的血管重塑。此外,移植物中还检测到细胞角蛋白5 (Cytokeratin 5,K5) 和细胞角蛋白8 (Cytokeratin 8,K8),二者均为TECs的标记物,分别对应胸腺mTECs层和cTECs层。以上结果说明,将淋巴结作为胸腺细胞的移植位置,不仅有助于移植物实现血管化(Vascularization),更能促进移植物中的TECs分层,形成与胸腺内部微环境高度相似的立体结构。此外,通过自组装或三维打印制作的生物相容性水凝胶可以促进TECs的聚集[49]。如果以这类水凝胶作为胸腺类器官的支架,有助于其在移植后维持正常的结构和功能。

Lenti等[50]通过手术、放射治疗或感染等方式建立小鼠淋巴管系统受损模型,再将培养出的正常淋巴结类器官移植到小鼠腋下。淋巴结类器官融入受体自身的淋巴管,恢复了淋巴的引流和灌注;同时类器官中含有大量T细胞和B细胞簇,支持了小鼠的抗原特异性免疫。由此可见,相比肾包膜或皮下,淋巴结可能更适合胸腺类器官移植。但目前尚无将胸腺类器官移植到淋巴结的案例,因此还需要进一步探究。

4.3 研究胸腺瘤与免疫细胞的相互作用2000年,Hoffacker等[51]提出了细胞免疫和体液免疫联合机制学说,认为细胞免疫和体液免疫可能联合参与了胸腺瘤相关自身免疫病的发生。胸腺瘤是唯一被证明可以从未成熟的前体T细胞产生成熟T细胞的肿瘤。胸腺瘤产生自身抗原特异性T细胞,肿瘤内T细胞输出后引起的血液循环中的T细胞亚群紊乱,进而激活B细胞产生攻击自身的抗体。这一学说已经得到了大量临床案例的支持[52-54],许多胸腺瘤合并系统性红斑狼疮(Systemic lupus erythematosus,SLE) 或重症肌无力(Myasthenia gravis,MG) 的患者血液中都存在多种自身抗体和异常的自身免疫性CD4+SP T细胞。部分患者切除胸腺瘤后,出现了自身抗体滴度下降。当前肿瘤类器官-免疫细胞共培养系统[55]正在蓬勃发展,在研究抗感染免疫和损伤后免疫、肿瘤和免疫系统之间复杂的动态相互作用等方面均有良好的前景,但胸腺瘤类器官-免疫细胞共培养系统的相关研究仍处于空白状态。如果开发出这样的系统,将十分有利于胸腺瘤与多种自身免疫性疾病错综复杂的发生机制的探究,更好地指导治疗并采取预防措施。

4.4 优化HSCs的培养环境不同于小肠、肺等类器官,无支架的胸腺类器官不进行连续传代,而是持续培养12周及以上[10, 19, 21]。胸腺类器官的培养主要受到HSCs的限制。一方面,人体中的HSCs十分稀少,从CB、BM和PB等新鲜样本中提取HSCs时很难保证稳定的数量和活性;另一方面,根据我们的培养经验,现有的无支架胸腺类器官培养基主要添加促进HSCs定向分化为T细胞的细胞因子(例如IL-7、FLT3L)[10, 19, 21],HSCs在培养基刺激下虽然可以实现数目增加,但同时其长期重建血液的能力(干性) 会逐渐下降甚至完全丢失。气液界面培养是上皮类器官的经典培养方法,目前无支架胸腺类器官主要依靠孔径0.4 μm的插入式细胞培养皿进行气液界面培养。插入式细胞培养皿通过其低吸附平面为胸腺类器官提供支撑作用,保证其在不使用支架的前提下保持穹顶状,同时完成物质交换。如果用其他结构立体、可以添加生物活性成分的材料(例如覆盖有粘连蛋白的3D碳质基质[56]、用陶瓷泡沫制作的类骨质3D基质[57]) 代替功能单一的Transwell insert支撑无支架胸腺类器官,可能有助于这一问题的解决。

尽管目前尚无胸腺类器官用于临床治疗的报道,但是它对T细胞在体外的成熟和分化研究的推动作用是不可忽视的。胸腺类器官有望成为重建免疫功能不全的患者和(或) 老年群体的适应性免疫系统、建立胸腺相关疾病模型以及在体外生成具有靶向特定癌细胞受体T细胞的有力工具。

| [1] |

Ma D, Wei Y, Liu F. Regulatory mechanisms of thymus and T cell development. Dev Comp Immunol, 2013, 39(1-2): 91-102. DOI:10.1016/j.dci.2011.12.013

|

| [2] |

Shah DK, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. An overview of the intrathymic intricacies of T cell development. J Immunol, 2014, 192(9): 4017-4023. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1302259

|

| [3] |

Orlando G. Immunosuppression-free transplantation reconsidered from a regenerative medicine perspective. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2012, 8(2): 179-187. DOI:10.1586/eci.11.101

|

| [4] |

Kennedy M, D'Souza SL, Lynch-Kattman M, et al. Development of the hemangioblast defines the onset of hematopoiesis in human ES cell differentiation cultures. Blood, 2007, 109(7): 2679-2687. DOI:10.1182/blood-2006-09-047704

|

| [5] |

Grigoriadis AE, Kennedy M, Bozec A, et al. Directed differentiation of hematopoietic precursors and functional osteoclasts from human ES and iPS cells. Blood, 2010, 115(14): 2769-2776. DOI:10.1182/blood-2009-07-234690

|

| [6] |

Ledran MH, Krassowska A, Armstrong L, et al. Efficient hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on stromal cells derived from hematopoietic niches. Cell Stem Cell, 2008, 3(1): 85-98. DOI:10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.001

|

| [7] |

Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science, 2014, 345(6194): 1247125. DOI:10.1126/science.1247125

|

| [8] |

Fatehullah A, Tan SH, Barker N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat Cell Biol, 2016, 18(3): 246-254. DOI:10.1038/ncb3312

|

| [9] |

Poznansky MC, Evans RH, Foxall RB, et al. Efficient generation of human T cells from a tissue-engineered thymic organoid. Nat Biotechnol, 2000, 18(7): 729-734. DOI:10.1038/77288

|

| [10] |

Seet CS, He C, Bethune MT, et al. Generation of mature T cells from human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in artificial thymic organoids. Nat Methods, 2017, 14(5): 521-530. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.4237

|

| [11] |

Suematsu S, Watanabe T. Generation of a synthetic lymphoid tissue-like organoid in mice. Nat Biotechnol, 2004, 22(12): 1539-1545. DOI:10.1038/nbt1039

|

| [12] |

Fan Y, Tajima A, Goh SK, et al. Bioengineering thymus organoids to restore thymic function and induce donor-specific immune tolerance to allografts. Mol Ther, 2015, 23(7): 1262-1277. DOI:10.1038/mt.2015.77

|

| [13] |

Tajima A, Pradhan I, Geng X, et al. Construction of thymus organoids from decellularized thymus scaffolds. Methods Mol Biol, 2019, 1576: 33-42.

|

| [14] |

Clark RA, Yamanaka K, Bai M, et al. Human skin cells support thymus-independent T cell development. J Clin Invest, 2005, 115(11): 3239-3249. DOI:10.1172/JCI24731

|

| [15] |

Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G, Owen JJ. Studies on T cell maturation on defined thymic stromal cell populations in vitro. J Exp Med, 1992, 176(3): 845-853. DOI:10.1084/jem.176.3.845

|

| [16] |

Campinoti S, Gjinovci A, Ragazzini R, et al. Reconstitution of a functional human thymus by postnatal stromal progenitor cells and natural whole-organ scaffolds. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 6372. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-20082-7

|

| [17] |

Vizcardo R, Klemen ND, Islam SMR, et al. A three-dimensional thymic culture system to generate murine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived tumor antigen-specific thymic emigrants. J Vis Exp, 2019, 22(12): 3175-3190.

|

| [18] |

Schmitt TM, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Induction of T cell development from hematopoietic progenitor cells by delta-like-1 in vitro. Immunity, 2002, 17(6): 749-756. DOI:10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00474-0

|

| [19] |

Montel-Hagen A, Seet CS, Li S, et al. Organoid-induced differentiation of conventional T cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell, 2019, 24(3): 376-389. DOI:10.1016/j.stem.2018.12.011

|

| [20] |

Montel-Hagen A, Sun V, Casero D, et al. In vitro recapitulation of murine thymopoiesis from single hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Rep, 2020, 33(4): 108320. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108320

|

| [21] |

Bosticardo M, Pala F, Calzoni E, et al. Artificial thymic organoids represent a reliable tool to study T-cell differentiation in patients with severe T-cell lymphopenia. Blood advances, 2020, 4(12): 2611-2616. DOI:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001730

|

| [22] |

van Boxtel R, Gomez-Puerto C, Mokry M, et al. FOXP1 acts through a negative feedback loop to suppress FOXO-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ, 2013, 20(9): 1219-1229. DOI:10.1038/cdd.2013.81

|

| [23] |

Nunes-Cabaço H, Sousa AE. Repairing thymic function. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2013, 18(3): 363-368. DOI:10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283615df9

|

| [24] |

Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, et al. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1999, 81(5): 907-914. DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.81B5.0810907

|

| [25] |

Marshall D, Bagley J, Le P, et al. T cell generation including positive and negative selection ex vivo in a three-dimensional matrix. J Hematother Stem Cell Res, 2003, 12(5): 565-574. DOI:10.1089/152581603322448277

|

| [26] |

Bertoni A, Alabiso O, Galetto AS, et al. Integrins in T cell physiology. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(2): 485. DOI:10.3390/ijms19020485

|

| [27] |

Gostynska N, Shankar Krishnakumar G, Campodoni E, et al. 3D porous collagen scaffolds reinforced by glycation with ribose for tissue engineering application. Biomed Mater, 2017, 12(5): 055002. DOI:10.1088/1748-605X/aa7694

|

| [28] |

Pinto S, Schmidt K, Egle S, et al. An organotypic coculture model supporting proliferation and differentiation of medullary thymic epithelial cells and promiscuous gene expression. J Immunol, 2013, 190(3): 1085-1093. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1201843

|

| [29] |

Ghosh S, Viana JC, Reis RL, et al. The double porogen approach as a new technique for the fabrication of interconnected poly (L-lactic acid) and starch based biodegradable scaffolds. J Mater Sci Mater Med, 2007, 18(2): 185-193. DOI:10.1007/s10856-006-0680-y

|

| [30] |

Palamaro L, Guarino V, Scalia G, et al. Human skin-derived keratinocytes and fibroblasts co-cultured on 3D poly ε-caprolactone scaffold support in vitro HSC differentiation into T-lineage committed cells. Int Immunol, 2013, 25(12): 703-714. DOI:10.1093/intimm/dxt035

|

| [31] |

Tavakol DN, Tratwal J, Bonini F, et al. Injectable, scalable 3D tissue-engineered model of marrow hematopoiesis. Biomaterials, 2020, 232: 119665. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119665

|

| [32] |

Bortolomai I, Sandri M, Draghici E, et al. Gene modification and three-dimensional scaffolds as novel tools to allow the use of postnatal thymic epithelial cells for thymus regeneration approaches. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2019, 8(10): 1107-1122. DOI:10.1002/sctm.18-0218

|

| [33] |

Hun M, Barsanti M, Wong K, et al. Native thymic extracellular matrix improves in vivo thymic organoid T cell output, and drives in vitro thymic epithelial cell differentiation. Biomaterials, 2017, 118: 1-15. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.054

|

| [34] |

Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM. Malignant thymoma in the United States: demographic patterns in incidence and associations with subsequent malignancies. Int J Cancer, 2003, 105(4): 546-551. DOI:10.1002/ijc.11099

|

| [35] |

Palmieri G, Marino M, Buonerba C, et al. Imatinib mesylate in thymic epithelial malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2012, 69(2): 309-315. DOI:10.1007/s00280-011-1690-0

|

| [36] |

Chuah C, Lim TH, Lim AS, et al. Dasatinib induces a response in malignant thymoma. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(34): e56-e58. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8963

|

| [37] |

Drost J, Clevers H. Organoids in cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer, 2018, 18(7): 407-418. DOI:10.1038/s41568-018-0007-6

|

| [38] |

Weeber F, van de Wetering M, Hoogstraat M, et al. Preserved genetic diversity in organoids cultured from biopsies of human colorectal cancer metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(43): 13308-13311. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1516689112

|

| [39] |

Lee SH, Hu W, Matulay JT, et al. Tumor evolution and drug response in patient-derived organoid models of bladder cancer. Cell, 2018, 173(2): 515-528. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.017

|

| [40] |

Samal J, Kelly S, Na-Shatal A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection induces lymphoid fibrosis in the BM-liver-thymus-spleen humanized mouse model. JCI Insight, 2018, 3(18): e120430. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.120430

|

| [41] |

Bobardt M, Kuo J, Chatterji U, et al. The inhibitor of apoptosis proteins antagonist Debio 1143 promotes the PD-1 blockade-mediated HIV load reduction in blood and tissues of humanized mice. PLoS One, 2020, 15(1): e0227715. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0227715

|

| [42] |

Tajima A, Pradhan I, Trucco M, et al. Restoration of thymus function with bioengineered thymus organoids. Curr Stem Cell Rep, 2016, 2(2): 128-139. DOI:10.1007/s40778-016-0040-x

|

| [43] |

Yamada K, Gianello PR, Ierino FL, et al. Role of the thymus in transplantation tolerance in miniature swine. I. Requirement of the thymus for rapid and stable induction of tolerance to class I-mismatched renal allografts. J Exp Med, 497-506.

|

| [44] |

Nobori S, Samelson-Jones E, Shimizu A, et al. Long-term acceptance of fully allogeneic cardiac grafts by cotransplantation of vascularized thymus in miniature swine. Transplantation, 2006, 81(1): 26-35. DOI:10.1097/01.tp.0000200368.03991.e0

|

| [45] |

Lockridge JL, Zhou Y, Becker YA, et al. Mice engrafted with human fetal thymic tissue and hematopoietic stem cells develop pathology resembling chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2013, 19(9): 1310-1322. DOI:10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.007

|

| [46] |

Chung B, Montel-Hagen A, Ge S, et al. Engineering the human thymic microenvironment to support thymopoiesis in vivo. Stem Cells, 2014, 32(9): 2386-2396. DOI:10.1002/stem.1731

|

| [47] |

Ham O, Jin YB, Kim J, et al. Blood vessel formation in cerebral organoids formed from human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2020, 521(1): 84-90. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.079

|

| [48] |

Komori J, Boone L, DeWard A, et al. The mouse lymph node as an ectopic transplantation site for multiple tissues. Nat Biotechnol, 2012, 30(10): 976-983. DOI:10.1038/nbt.2379

|

| [49] |

Escors D, Breckpot K. Lentiviral vectors in gene therapy: their current status and future potential. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz), 2010, 58(2): 107-119. DOI:10.1007/s00005-010-0063-4

|

| [50] |

Lenti E, Bianchessi S, Proulx ST, et al. Therapeutic regeneration of lymphatic and immune cell functions upon lympho-organoid transplantation. Stem Cell Reports, 2019, 12(6): 1260-1268. DOI:10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.04.021

|

| [51] |

Hoffacker V, Schultz A, Tiesinga JJ, et al. Thymomas alter the T-cell subset composition in the blood: a potential mechanism for thymoma-associated autoimmune disease. Blood, 2000, 96(12): 3872-3879. DOI:10.1182/blood.V96.12.3872

|

| [52] |

Noël N, Le Roy A, Hot A, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus associated with thymoma: a fifteen-year observational study in France. Autoimmun Rev, 2020, 19(3): 102464. DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102464

|

| [53] |

Zekeridou A, McKeon A, Lennon VA. Frequency of synaptic autoantibody accompaniments and neurological manifestations of thymoma. JAMA Neurol, 2016, 73(7): 853-859. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0603

|

| [54] |

Lee CM, Lee JD, Hobson-Webb LD, et al. Treatment of thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis with stereotactic body radiotherapy: a case report. Ann Intern Med, 2016, 165(4): 300-301. DOI:10.7326/L15-0469

|

| [55] |

Jacob F, Ming GL, Song H. Generation and biobanking of patient-derived glioblastoma organoids and their application in CAR T cell testing. Nat Protoc, 2020, 15(12): 4000-4033. DOI:10.1038/s41596-020-0402-9

|

| [56] |

Ehring B, Biber K, Upton TM, et al. Expansion of HPCs from cord blood in a novel 3D matrix. Cytotherapy, 2003, 5(6): 490-499. DOI:10.1080/14653240310003585

|

| [57] |

Feng Q, Chai C, Jiang XS, et al. Expansion of engrafting human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in three-dimensional scaffolds with surface-immobilized fibronectin. J Biomed Mater Res A, 2006, 78(4): 781-791.

|