中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 陈心宇, 李梦怡, 陈国强

- Chen Xinyu, Li Mengyi, Chen Guo-qiang

- 聚羟基脂肪酸酯PHA代谢工程研究30年

- Thirty years of metabolic engineering for biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates

- 生物工程学报, 2021, 37(5): 1794-1811

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2021, 37(5): 1794-1811

- 10.13345/j.cjb.200457

-

文章历史

- Received: July 26, 2020

- Accepted: October 13, 2020

- Published: November 19, 2020

聚羟基脂肪酸酯(Polyhydroxyalkanoates,PHA) 是一类生物合成的高分子聚酯的统称,是部分微生物(主要是细菌) 在营养或代谢不平衡的条件下合成的一种储能物质[1]。PHA具有良好的生物可降解性和生物相容性,被公认为绿色环保型高分子材料;且由于其种类和性能的多样性,可被应用于大宗塑料、医学材料、生物燃料甚至饲料等诸多领域而受到广泛关注[2-5]。近年来随着代谢工程技术的发展,关于PHA的微生物合成也有了新的突破。本文介绍了近30年应用代谢工程技术拓展PHA的多样性、改造PHA合成相关通路、提高PHA合成效率、进行PHA的低成本生产等方面的进展,重点介绍以嗜盐单胞菌为底盘的“下一代工业生物技术”并提出展望。

1 PHA多样性及合成途径 1.1 PHA的单体组成及分类自20世纪20年代首次在微生物细胞内发现PHB (聚3-羟基丁酸,最常见的PHA) 以来[6],不断有新的PHA在不同的微生物菌体中被合成出来,目前已有超过150种PHA被研究报道[7]。PHA化学本质上是一种高分子聚酯,在细胞体内PHA聚合酶(PhaC) 的催化下,一定碳链长度的羟基脂肪酸相互连接形成酯键,最终形成不同类型、不同分子量的PHA聚酯[8]。

根据组成单体碳链长度的不同,PHA可以分为短链PHA (Short chain length PHA,SCL PHA)和中长链PHA (Medium chain length PHA,MCL PHA),其中短链PHA的单体碳链长度一般为3–5,而中长链PHA的单体碳链长度在6–14之间。一般来说,天然微生物只能积累SCL PHA或MCL PHA中的一类。

根据组成单体种类的多少,PHA可以分为均聚物(Homopolymer) 和共聚物(Copolymer),后者可进一步细分为随机共聚物(Random copolymer) 和嵌段共聚物(Block copolymer)。

此外,由于PHA单体的侧链R基团十分多样,理论上可以引入具有双键或三键、卤素、氨基、苯环等功能基团的单体[9-10],而这些基团又允许通过后期无限可能性的化学修饰增加新的官能团,形成所谓的“功能PHA”。功能PHA能够改善材料性能,并带来诸如温敏、光敏、pH值调节等特殊材料功能[11-14]。

因此,取决于PHA的单体种类及比例、聚合形式、侧链基团、分子量等,形成了丰富的PHA结构,由此带来了材料性能上的多样性,包括PHA热力学性能、生物相容性和生物可降解性及其他性能,拥有广阔的应用前景。

PHA的结构通式、多样性示意见图 1。

|

| 图 1 PHA结构通式及多样性 Fig. 1 General molecular formula and PHA diversity. |

| |

微生物合成的PHA在很大程度上依赖于所供给的碳源,简单地说,这些碳源可以分为相关碳源和非相关碳源两类。PHA生物合成过程中有多条代谢途径能够合成羟基脂酰辅酶A单体,这些途径又与体内的中心代谢途径相耦联,形成一个巨大的代谢网络。不同细菌利用的碳源不同,所使用的PHA合成途径不同,合成PHA的种类也不同,这种差异与特定微生物中起作用的代谢途径有关。

目前,在自然条件下细菌中已经报道的PHA单体的合成途径一共有14种[9]。其中,最常见也是代谢工程改造研究最为成熟的,是与SCL PHA合成相关的乙酰辅酶A直接合成PHB途径,以及与MCL PHA合成相关的β氧化循环途径和脂肪酸从头合成途径(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 PHA的主要生物合成途径[6, 15-17] (PhaA:β-酮基硫解酶(β-ketothiolase);PhaB:NADPH/NADH依赖型乙酰乙酰辅酶A还原酶(NADPH/NADH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase):PhaC:PHA聚合酶(PHA synthase);PhaG:3-羟基脂酰-ACP: CoA酰基转移酶(3-hydroxyacyl-ACP: CoA transacylase);PhaJ:(R)-烯脂酰辅酶A水合酶[(R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase];FabG:3-酮脂酰-ACP还原酶(3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase)) Fig. 2 Main PHA biosynthetic pathways[6, 15-17]. |

| |

精确的基因编辑技术使研究者可以根据需求对基因特定位点进行改造,从而在基因水平上对代谢通路进行调节。20世纪90年代,研究人员将可以特异性识别三联碱基对的锌指蛋白与核酸酶FokⅠ进行偶联,开发出了锌指蛋白核酸酶技术(Zinc finger nucleases,ZFNs)。但因其识别的DNA序列数量有限,很大程度上也被限制了应用[18-19]。随后,根据改造的黄单胞菌属的TAL蛋白可以特异性识别DNA中一个碱基的特点,研究人员又开发出了类转录激活因子效应物核酸酶技术(Transcription activator-like effector nucleases,TALENs)。此技术理论上可以对任意基因序列进行编辑,但因其操作较为烦琐,应用同样受到了限制[19-20]。近年来,随着成簇规律间隔短回文重复序列/成簇规律间隔短回文重复序列关联蛋白(Clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein,CRISPR/Cas)的发现,基因编辑技术有了重要突破[21-22]。CRISPR/Ca是细菌和古菌中普遍存在的天然免疫系统,研究人员对其加以利用,开发出新一代基因编辑技术CRISPR/Cas9,可对靶向基因位点进行剪切[23-24]。与之前的技术相比,CRISPR/Cas9更加灵活、高效、廉价且操作简便。基于CRISPR/Cas9开发出的CRISPRi (CRISPR interference) 和CRISPRa (CRISPR activation) 技术可以在不改变DNA的情况下可逆地抑制或上调基因表达,大大扩展了CRISPR/Cas9工具箱[25-26]。

将各种技术结合使用可以满足多种基因调节需求,为研究带来极大的便利。这些基因编辑工具已经在调节PHA相关代谢通路、导入外源代谢途径、改变细胞形态等各方面发挥出巨大的作用,为增强PHA生产助力[27]。

2.2 代谢工程增强PHA生产 2.2.1 代谢流调控增加PHA产量在生物获取的物质和能量一定的情况下,将这些物质和能量更多地引向PHA相关通路,理论上可以积累更多的PHA。在PHA发现之初,研究者就通过控制培养条件对PHA的合成、降解等特性进行研究,以求得到更高的产率[28-31]。而后通过提供不同的前体在多种细菌中发现了不同种类的PHA[32]。直到1989年在罗氏真氧菌Ralstonia eutropha中首次鉴定了PHA生物合成操纵子phaCAB,自此开始了针对phaCAB等PHA合成相关基因的调控[33-34]。

PHA合成相关基因稳定的强表达对于把底物引向PHA合成方向、提高底物转化率从而增加PHA积累是至关重要的,其中又以PHA聚合酶PhaC最为关键。PhaC决定着合成的PHA的诸多特性,包括产率、单体类型和组成、分子量及多分散性[35]。为增强PhaC的活性和改变底物特异性,研究人员已经在PhaC的编辑上进行了很多研究。在近年PhaC的晶体结构被解析之前[36-38],编辑PhaC的方法主要依赖于随机诱变和筛选以及基于序列同源性的结构预测[39-41]。例如,通过对假单胞菌Pseudomonas sp. 61-3的随机诱变和筛选,研究者发现Glu130、Ser325、Ser477和Gln481是决定PhaC底物特异性和活性的重要残基。与野生型相比,Glu130Asp、Ser325Thr、Ser477Gly和Gln481Lys的突变体有更强的聚合活性,可以使PHB产量增加400倍[42-44]。

之后又开发出了很多方法调控PHA合成相关基因的表达。比如将大肠杆菌Escherichia coli JM109基因组上phaCAB的拷贝数从11增加至50,可以使PHB积累量从0.1 g/L增加至1.30 g/L。这项实验结果表明,更高的PHA合成基因拷贝数可带来更高的PHA产量[45]。此外还可以用强诱导转录系统过表达PHA合成基因,研究人员开发了一种由噬菌体聚合酶衍生的类T7诱导系统,实验表明该系统在诱导后有较强的转录活性[46]。在盐单胞菌Halomonas bluephagenesis的基因组上整合该类T7启动子驱动的phaCAB基因,诱导44 h后,PHA产量达到了69 g/L,而同样条件下野生型只积累了50 g/L PHA。

插入或删除基因也是一种增强PHA生产的常用策略,但是这种方法往往只注重局部的通路设计而忽略对细胞生长产生的不利影响。在现代计算机技术的帮助下,结合代谢流建模对细菌生产途径进行电脑模拟有助于设计和优化通路以达到最优的产品生产[47]。例如,现在已经建立了恶臭假单胞菌Pseudomonas putida代谢流的电脑模拟模型,用于预测底物向PHA合成酶及前体转化的最佳流量。初步的模拟分析显示,敲除葡萄糖脱氢酶(Gcd) 的菌株与野生型相比,PHA积累量可增加100%。在实验中,敲除Gcd的P. putida表现出了更高的PHA产量(+80%) 和胞内PHA含量(+50%),同时生成的副产物也更少,而且细菌生长几乎没有受到影响。这样构建的重组菌在所有工业生产相关评价标准下都是最优的[48]。同样地,根据初步模型预测,P. putida KT2440中过表达丙酮酸脱氢酶亚基(AcoA) 的同时敲除Gcd可以使PHA产量增加120%,实际实验中PHA产量增加了121%[47]。

2.2.2 构建重组通路利用廉价原料生产PHA得益于近几十年来在生物化学和分子生物学领域对PHA生物合成愈加透彻的理解,以及对许多细菌中PHA合成基因的成功克隆,多种细菌通过代谢工程改造成为了高性价比的PHA生产平台。其中最具有代表性的例子就是带有来源于R. eutropha的phaCAB操纵子的E. coli,这种改良的E. coli拥有能与原始R. eutropha相媲美的高PHB产量和产率[49-51]。通过导入适合的PhaC,E. coli、R. eutropha、Pseudomonas sp.等菌种还可被用来更高效地生产SCL-co-MCL PHA[52-55]。除细菌外,酵母和一些植物也被成功改造,可进行PHA生产[56-57]。

同时构建重组代谢通路避免使用昂贵的相关碳源也是利用代谢工程降低PHA生产成本的重要思路。例如,最初聚3-羟基丁酸-3-羟基戊酸(PHBV) 生产需要添加丙酸或戊酸钠生成3HV的中间体丙酰辅酶A[58-59],为了避免使用这些高价格的前体,研究人员构建了通过α-酮丁酸和甲基丙二酰辅酶A生产丙酰辅酶A的通路,以用更廉价的非相关碳源生产PHBV[60-62]。类似地,生产聚3-羟基丁酸-4-羟基丁酸(P34HB) 通常需要使用γ-丁内酯或丁酸[59, 63],作为更经济的选择,可以利用克氏梭菌Clostridium kluyveri的琥珀酸半醛脱氢酶(SucD) 和4HB脱氢酶(4HbD) 从葡萄糖生产4HB[64-65]。通过导入编码β-呋喃果糖苷酶的sacC基因,可在R. eutropha NCIMB11599和R. eutropha 437-540中构建蔗糖利用通路。β-呋喃果糖苷酶被分泌到培养基中,将蔗糖水解为葡萄糖和果糖以供细胞生长。在含20 g/L蔗糖的无氮培养基中生长的R. eutropha NCIMB11599可获得占细胞干重73%的PHB[66]。

此外还有许多利用菌种独特代谢通路使用各种廉价原料进行PHA生产以求降低成本的研究,比如蔗糖蜜、木薯和玉米淀粉、木质纤维素水解物、乳清以及废弃物中提取的碳源等[59, 67-71]。近年来也出现了很多针对利用气体碳源如CO、CO2、CH4等生产PHA的研究,例如甲烷氧化菌Methylosinus trichosporium、R. eutropha、聚球菌Synechococcus sp. 等一系列天然PHA生产菌都有以气体一碳底物作为碳源生产PHA的能力[72-74]。

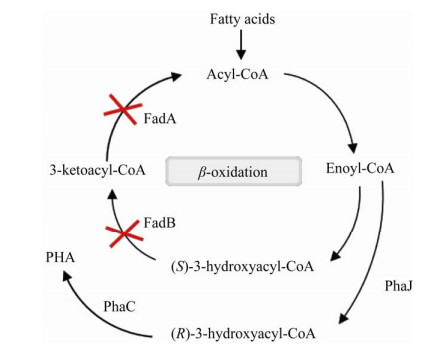

2.2.3 改造β氧化途径利用脂肪酸高效合成不同链长PHAβ氧化途径是PHA合成的3条主要途径之一,选用脂肪酸作为底物来提供短链和中长链单体生产PHA是经常采取的方法[75-79],对β氧化途径进行改造对于促进MCL PHA或短中长链共聚PHA (SCL-co-MCL PHA) 的合成具有重要意义。在1994年首次报道了豚鼠气单胞菌Aeromonas caviae能利用烷酸和油生产聚3-羟基丁酸-3-羟基己酸(PHBHHx) 的随机共聚物[80]。β氧化是这个过程中的主要通路,脂酰辅酶A脱氢酶(FadE) 催化脂酰辅酶A生成烯酰辅酶A的反应是β氧化过程中的限速步骤。有研究表明,在E. coli中过表达FadE可以使烯酰辅酶A的量增多,再表达PhaJ和PhaC可以使重组菌积累更多的PHA[81]。

然而在β氧化过程中细胞可能会将大部分脂肪酸转化为乙酰辅酶A用于细胞生长,从而将昂贵的脂肪酸浪费在能用葡萄糖等廉价底物生产的乙酰辅酶A上[64-65, 82]。因为β氧化的存在,脂肪酸转化为PHA的效率低,导致MCL PHA生产成本升高。因此,改造β氧化途径也是提高PHA生产效率的一种可行策略。

敲除P. putida或嗜虫假单胞菌Pseudomonas entomophila内β氧化途径中3-羟基脂酰辅酶A脱氢酶(FadB) 及3-酮脂酰辅酶A硫解酶(FadA)可以使大多数脂肪酸转变成3-羟基脂酰辅酶A用于合成PHA,而不是被氧化成乙酰辅酶A,从而显著提高底物到MCL PHA的转化率[82-85]。据报道,部分敲除β氧化途径或者利用丙烯酸抑制β氧化可以获得与底物添加脂肪酸链长相同或更长的单体,底物中各种脂肪酸的比例还可以影响PHA的组成成分[85-86]。部分敲除β氧化的P. putida KT2442可作为可控的PHA生产平台,通过添加预定比例的脂肪酸精确调节PHA的单体比例,并以此合成了随机和嵌段共聚物聚3-羟基丁酸-3-羟基己酸[P(3HB-co-3HHx)],单体组成和材料性能稳定[87-88]。类似地,通过部分敲除β氧化途径和导入乙酰辅酶A直接合成PHB途径,重组P. entomophila LAC32被成功开发成SCL-co-MCL PHA的合成平台,并合成了聚3-羟基丁酸-3-羟基癸酸[P(3HB-co-3HD)]、聚3-羟基丁酸-3-羟基十二酸[P(3HB-co-3HDD)] 等多种新型PHA[89]。Pseudomonas spp.脂肪酸氧化突变体还可以生成包含3-羟基己酸(3HHx)、3-羟基辛酸(3HO)、3-羟基癸酸(3HD) 和3-羟基十二酸(3HDD) 的均聚、无规共聚或嵌段共聚的中链PHA[10]。但值得注意的是,只使用脂肪酸培养的β氧化缺陷菌可能会生长缓慢或只积累少量的MCL PHA[86, 90-91]。

2.2.4 设计引入新通路生产非天然PHA以各种经过充分研究的通路作为基础,可以从目的产物出发设计构建新的生产通路。例如,乳酸和乙醇酸的共聚物(PLGA) 是一种应用广泛的可生物降解、高生物相容性的医用聚合物。在导入了新月柄杆菌Caulobacter crescentus的Dahms途径并敲除了磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸-糖磷酸转移酶系统中葡萄糖转运体亚基(PtsG) 后,重组E. coli可以以木糖为原料生产乙醇酸。这种E. coli可以同时利用葡萄糖生产乳酸并用木糖生产乙醇酸。之后用一种进化的丙酰辅酶A转移酶将乳酸和乙醇酸在体内转化为CoA中间体。最后利用进化的PHA聚合酶将这些CoA中间体聚合成PLGA[92]。如图 4所示,用相似的方法还合成了聚2-羟基丁酸-3-羟基丁酸、聚乳酸-羟基乙酸-3-羟基丁酸-4-羟基丁酸等多种聚合物,以及一些芳香族聚酯[93-97]。通过编辑L-苯丙氨酸生物合成途径,可以使E. coli利用葡萄糖有效生产含苯乳酸(PhLA) 的聚合物。在这条通路中,磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸(PEP) 和赤藓糖-4-磷酸(E4P) 依次转化为3-脱氧-D-阿拉伯庚酮糖酸-7-磷酸(DAHP)、预苯酸、苯丙酮酸、PhLA、PhLA-CoA[97-98];同时构建了由L-苯丙氨酸合成肉桂酰辅酶A的通路,作为辅酶A的供体[97]。

|

| 图 4 引入新通路构建多种单体PHA生产途径[93-96]((R)-citramalate:(R)-柠苹酸;2-ketobutyrate:2-酮丁酸;2-hydroxybutyrate-CoA:2-羟基丁酰辅酶A;3-hydroxybutyrate-CoA:3-羟基丁酰辅酶A;Citrate:柠檬酸;Succinyl-CoA:琥珀酰辅酶A;Succinate:琥珀酸;4-hydroxybutyrate-CoA:4-羟基丁酰辅酶A;Lactate:乳酸;Lactyl-CoA:乳酰辅酶A;Xylose:木糖;Xylonolactone:木糖酸内酯;Xylonate:木糖酸;2-keto-3-deoxy-xylonate:2-酮基-3-脱氧木糖酸;Glycolaldehyde:乙醇醛;Glycolate:乙醇酸;Glycolyl-CoA:羟乙酰辅酶A) Fig. 4 Introducing new pathways to produce PHA with various monomers[93-96]. |

| |

经过近30年的产业化探索,PHA的大规模应用仍然面临困难。相较于传统石油基塑料制品,PHA严重受制于它高昂的生产成本。为降低PHA的生产成本,从而提升其在材料市场上的竞争力,近年来,研究人员在运用代谢工程技术改造PHA生产菌株以简化下游加工过程上取得了一些新进展。

3.1 形态学工程工业生物技术通常涉及在大型发酵罐中进行微生物发酵,然后进行下游加工处理,即从发酵培养液中分离出微生物生物质,再分离提取胞内产物或上清液产物。而实现分离通常需要昂贵且耗能大的连续离心、微过滤或费时的重力沉淀等。

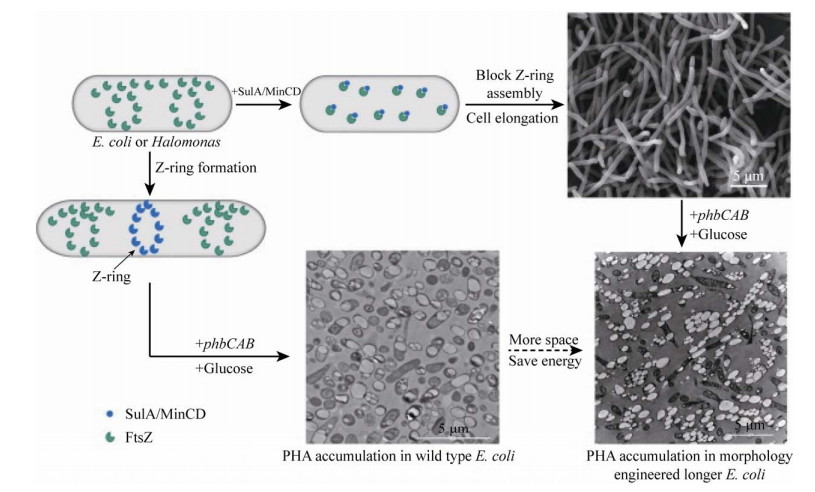

PHA的生产成本高昂的一个重要因素就是细菌细胞及胞内产物PHA的下游加工过程花费较高。由于大多数菌株细胞的大小在0.5–2.0 μm之间,较小的细胞不仅增加了细菌生物量与培养液的分离难度,同时也限制了每个细胞中PHA颗粒的储存量。通过形态学工程改造PHA生产菌株,有助于提供更大的细胞空间来积累PHA颗粒;还有助于加速细胞沉淀,使细菌细胞易于通过重力与培养液分离,从而有效降低PHA的生产成本[99-101]。

细胞的形态受许多基因调控影响,包括细胞壁装配相关基因mreB (编码细胞骨架肌动蛋白MreB)、mreC (编码杆状细胞形状决定蛋白MreC)、mreD (编码杆状细胞形状决定蛋白MreD)、rodZ (编码细胞骨架蛋白RodZ)、rodA (编码杆状细胞形状决定蛋白RodA)、pbp2 (编码青霉素结合蛋白PBP2)、pbp3 (编码青霉素结合蛋白PBP3)、细胞分裂相关基因ftsZ (编码细胞分裂蛋白FtsZ)、ftsA (编码细胞分裂蛋白FtsA)、sulA (编码细胞分裂抑制蛋白SulA)、minC (编码Z环定位蛋白MinC) 和minD (编码Z环定位蛋白MinD)等[102]。在这些基因中,已在大肠杆菌或嗜盐菌中成功操作mreB、ftsZ、sulA、minC和minD基因来改造细胞形态,简化下游生物加工过程。

SulA是一种细胞分离抑制蛋白,当与细胞分裂的Z环相互作用时,SulA的过表达会阻止细胞分裂,从而将正常的杆状大肠杆菌转变成丝状细胞[103]。丝状化增加了细胞体积,为PHA颗粒的积累提供了更多空间(图 5)。相比于野生型E. coli,过表达SulA抑制Z环形成的丝状细胞能够比野生型多储存27%的PHB[101]。

MreB是一种细菌细胞骨架肌动蛋白,用以维持许多细菌的杆状形态[104],也被认为是用于扩大细胞体积的合适靶标。当在mreB缺失突变体中回补表达mreB后,细胞形态变为更大的球形,并且观测到在重组大肠杆菌中PHB的积累量可增加100%以上[99]。

由MinD募集到细胞极的MinC是与FtsZ相互作用以抑制Z环组装的蛋白质[105]。类似于SulA诱导大肠杆菌丝状细胞的形成,在H. bluephagenesis TD08的生长静止期中,过表达MinCD抑制剂可诱导产生丝状细胞(图 5),使PHA含量从69%增至82%[106]。并且观测到细胞形成了数百微米的相互缠绕的纤维网络,其中较短的细胞在重力作用下一起包装和沉淀,与正常的离心分离相比,可以更轻松地将细胞从培养液中分离出来,这大大简化了生物质的下游加工过程[106]。此外,当MinCD在敲除了PHA颗粒相关蛋白(PhaP) 的H. bluephagenesis菌株中过表达时,观测到最大可积累的PHA颗粒大小达10 μm[100]。

3.2 自絮凝生物自絮凝是指某些微生物自发展现出受控聚集的能力,形成大量且高度致密的细胞絮凝物,从而降低从培养基中回收生物质的难度,有利于实现简单经济的下游处理[107-108]。例如,当删除了盐单胞菌Halomonas campaniensis LS21编码电子转移链中两个电子转移黄素蛋白亚基的etf操纵子后,细胞表面电荷减少和细胞疏水性增加,细胞趋于自絮凝;在停止搅拌和通气后,大多数细胞迅速絮凝并沉淀至生物反应器的底部,整个过程持续不到1 min且没有能量消耗,从而减少了下游分离的能量消耗[109]。此外,自絮凝还拥有诸如发酵培养基循环再使用等其他优点。收集完沉淀的细胞团后,无需灭菌或接种,培养基上清液即可再次使用;无废水发酵工艺可以至少循环运行4次而不产生废水[109]。

4 下一代工业生物技术(Next generation industrial biotechnology,NGIB) 4.1 现代工业生物技术面临的问题随着分子生物学、生物化学和合成生物学的快速发展,工业生物技术已经发展成为生产化学品和材料更有效的手段。然而,与化学工业相比,目前的工业生物技术在生产化学品、材料和生物燃料等方面仍然存在生产成本较高、竞争力不足的问题。工业生物技术需要通过微生物的大规模发酵培养生产产品,因此在发酵过程中,如何廉价高效地避免杂菌污染是长久以来人们关注的重点。发酵过程中一旦沾染了杂菌,轻则降低物料利用率和产物收率,严重时则必须从头开始生产流程,带来极大的经济损失。在生产前对发酵设备进行灭菌处理是现在普遍采取的方法,然而这些方法也带来了不可忽视的高能耗成本,同时依然无法完全规避杂菌污染风险。因此必须进一步发展“下一代工业生物技术”,以更少的淡水消耗、节能和持久的开放式发酵为基础,克服目前工业生物技术的缺点,将目前的工业生物技术转化为具有竞争力的工艺。其中,以抗污染的极端微生物作为代谢改造及发酵培养的底盘菌株将会是NGIB成功的关键。

| Years | Types | Manipulations | Effects | Microorganisms | References |

| 1988 | Constructing recombinant pathways | +phaCAB operon from R. eutropha | Producing PHA in E. coli | E. coli | [50] |

| 1997 | +sucD and 4hbD from Clostridium kluyveri | Producing P34HB from glucose | E. coli | [64] | |

| 2002 | +Acinetobacter phaBCA and E. coli sbm and ygfG, ΔprpC | Producing PHBV with significant HV incorporation from glycerol | Salmonella enterica | [60] | |

| 2014 | +E. coli poxB L253F V380A, R. eutropha prpE, phaCABRe, ΔprpC ΔscpC | Producing P(3HB-co-5.5 mol% 3HV) from glucose | E. coli | [61] | |

| 2014 | Introducing sacC to construct sucrose utilization pathway | Producing 73 wt% PHB from nitrogen free medium containing 20 g/L sucrose | R. eutropha | [66] | |

| 2004 | Flux tuning for higher PHA accumulation | +phaABRe, phaJ4Pa, position 325 and 481 mutated PhaC1Ps | Accumulated more P(3HB-co-3HA) | E. coli | [42] |

| 2005 | +phbABRe, phaJ4Pa, phaC1Ps E130D | Accumulating 10-fold higher PHB from glucose; producing more P(3HB-co-3HA) copolymer grown on dodecanoate | E. coli | [43] | |

| 2006 | +phaABRe, phaJ4Pa, phaC1Ps S477R | Shifting in substrate specificity to smaller monomers containing a 3HB unit | E. coli | [44] | |

| 2014 | Pathway design guided by modeling simulation | An increase of 121% PHA accumulation | P. putida | [47] | |

| 2015 | Increasing the copy number of phaCAB | Enhancing PHB accumulation from 0.1 g/L to 1.30 g/L | E. coli | [45] | |

| 2017 | Overexpressing phaCAB by T7-like promoter | Enhancing PHB accumulation from 50 g/L to 69 g/L | H. bluephagenesis | [46] | |

| 1998 | Modification of β-oxidation pathway | +phaC1 from P. aeruginosa in fadR deletion mutant, adding acrylic acid | Accumulating 60 wt% PHA from decanoate | E. coli | [86] |

| 2009 | ΔfadBA | Producing PHA with 71 wt% P3HHp from heptanoate | P. putida | [83] | |

| 2010 | +fadE and phaC | Improved PHA production | E. coli | [81] | |

| 2010 | ΔfadBA ΔfadB2x ΔfadAx ΔPP2047 ΔPP2048 ΔphaG | Producing PHD or P(3HB-co-84 mol% 3HDD) from decanoic acid or dodecanoic acid | P. putida | [85] | |

| 2011 | ΔfadBA ΔPSEEN 0664 ΔPSEEN 2543 | Producing 90 wt% PHA with 99 mol% 3HDD | P. entomophila | [82] | |

| 2018 | ΔfadBA ΔPSEEN 0664 ΔPSEEN 4635 ΔPSEEN 4636 ΔphaG ΔphaC1-phaZ-phaC2 | Producing novel SCL-co-MCL PHA including P(3HB-co-3HD), P(3HB-co-3HDD) and P(3HB-co-3H9D) | P. entomophila | [89] | |

| 2012 | Producing non-natural polyesters | ΔldhA, +phaC1437, pct540, cimA3.7, leuBCD, panE from Lactococcus lactis Il1403 and phaAB from R. eutropha | Producing P(2HB-co-3HB-co-LA) with small amounts of 2HB and LA monomers from glucose | E. coli | [93] |

| 2016 | Introducing Dahms pathway in ptsG deletion mutant | Producing PLGA from glucose and xylose | E. coli | [92] | |

| 2016 | +ilvBNmut, ilvCD, panE, pct540 and phaC1437 | Producing PHA containing 2-hydroxyisovalerate | E. coli | [94] | |

| 2017 | Δsad ΔgabD ΔglcD, +p68pcH5Z and pMCS-ycdW-aceAK | Producing P(GA-co-LA-co-3HB-co-4HB) from glucose | E. coli | [96] | |

| 2018 | Manipulating L-phenylalanine biosynthesis pathway | Producing PhLA-containing polyesters | E. coli | [97-98] | |

| 1993 | Morphology engineering | +ftsZ | Accelerating cell division, high cell density with 127 g/L PHB | E. coli | [103] |

| 2014 | +sulA | Filamentary cells, PHB storage increased by 27% compared to wild type | E. coli | [101] | |

| 2014 | +minCD | Filamentary cells, enhancing PHA content from 69% to 82% | H. bluephagenesis | [106] | |

| 2015 | +mreB in mreB deletion mutant | Larger spherical cells, an increase of over 100% PHB accumulation | E. coli | [99] | |

| 2019 | +minCD in phaP deletion mutant | Accumulating PHA granules up to 10 μm | H. bluephagenesis | [100] | |

| 2018 | Self-flocculation | Δetf | Most cells rapidly flocculate and precipitate to the bottom in less than 1 min | H. bluephagenesis | [109] |

极端微生物可以在大多数微生物都无法增殖的苛刻条件下(诸如极端pH、极端温度或高渗透压) 生长,正因如此,它们在发酵过程中对杂菌有更强的抵抗能力。选择在极端条件下生长良好的稳健菌株作为底盘菌,并通过代谢工程导入新的通路或添加新的基因元件,可以使这种能力进一步增强,使其适合开放连续式的大规模发酵生产。

以PHA生产为例,结合多种生物工程技术,可以将极端微生物开发成优秀的PHA生产底盘菌,这不仅将简化生产流程也会显著降低PHA生产成本。嗜盐单胞菌H. bluephagenesis和H. campaniensis就是其中两个很好的例子,其能够在高盐浓度、高pH条件下快速生长,使得它们拥有其他微生物难能媲美的抗污染能力。据报道嗜盐菌在未经灭菌的海水培养基中可以持续开放发酵至少两个月而不被杂菌污染[110]。野生型H. bluephagenesis能在pH 8.0–9.0含有60 g/L NaCl的葡萄糖培养基中快速生长并积累高达细胞干重80%以上的PHA[111]。极端嗜盐古菌Natrinema ajinwuensis RM-G10也能在pH 7.0的200 g/L NaCl组成的高盐培养基中积累60%以上的PHA[112]。除嗜盐菌外,嗜热菌也被用作生产PHA的经济宿主。例如,嗜热的沙氏芽孢杆菌Bacillus shackletonii K5菌株可以在45 ℃和pH 7.0条件下合成高达其细胞干重73% (9.76 g/L) 的PHB[113]。

4.3 对基于极端微生物的NGIB进行的代谢改造下面将以H. bluephagenesis为例,分享改造NGIB菌株的经验,希望能起到抛砖引玉的作用。

从新疆艾丁湖分离出的中度嗜盐菌H. bluephagenesis可以在高盐浓度、高pH的含葡萄糖矿质培养基中快速生长并能利用多种碳源积累丰富的PHB。Zhao等在H. bluephagenesis基因组上整合了类T7表达系统调控phaCAB基因,显著增强了phaCAB的转录,提高了PHB产量[46]。Qin等在H. bluephagenesis中构建及优化了CRISPR/Cas9和CRISPRi系统,为高效基因组编辑奠定了基础[114]。Ling等通过阻断电子传递途径改变了H. bluephagenesis中NADH和NAD+的比例,增加了PHB的积累[115]。此外H. bluephagenesis还被改造为能生产P34HB、PHBV等PHA的底盘菌,Ye等在H. bluephagenesis中构建两条4HB合成途径的同时敲除了与4HB竞争的琥珀酸半醛脱氢酶,以葡萄糖为单一碳源在7 L发酵罐中非无菌开放发酵60 h得到了干重26.3 g/L的菌体和占干重的60.5%的P34HB,其中4HB摩尔比为17.04%[116]。尹进等插入甲基丙二酰辅酶A变位酶和脱羧酶(ScpAB),并敲除了2-甲基柠檬酸合成酶(PrpC) 后获得了能以葡萄糖为单一碳源稳定生产3HV含量为5–12 mol%的PHBV的菌株[45]。

4.4 NGIB面对的挑战尽管嗜盐菌已被设计成为PHA生产菌,其依然存在一些有待解决的问题,比如高盐造成的钢制设备锈蚀、诱导系统成本高、高盐废水处理和基因操作不便等问题[117-118]。借助合成生物学和代谢工程技术,部分阻碍嗜盐菌进一步工业开发的问题得到了一定的缓解,比如H. bluephagenesis适应高pH环境(pH > 8.5),而在这样的碱性条件下钢制品耐锈蚀能力较强;多种诱导体系也逐步引入菌株中以实现用温度、光线、pH或溶氧等方法实现低成本诱导[119-122]。相信在未来会有更多问题得到解决,使NGIB得到更广泛的应用。

5 总结与展望PHA因其具有良好的生物可降解性和生物相容性,以及种类和性能的多样性,受到广泛关注。随着越来越多的新型功能PHA被开发出来,PHA的应用面将进一步扩大。然而生产成本和热力学性能依然是制约PHA大规模生产和商业化的最大难题。

通过合成与系统生物学、代谢工程、下一代生物工业技术等手段,以极端微生物作为PHA的低成本生产平台菌株,可通过无需灭菌的开放式连续发酵,大大简化生物制造过程。同时,利用代谢工程和合成生物学技术对生产菌株进行改造,使更多的代谢流转向PHA合成,可以提高底物转向PHA的转化率;对菌株进行形态学、自絮凝改造,可以简化PHA下游提纯加工流程,从而大幅度降低PHA的生产成本。另一方面,还需要不断开发能够改善PHA性能的新单体(及最优的单体比例)、新结构和加工工艺等,使PHA热力学性能可以接近甚至超越石油基塑料,进一步促进PHA的应用与推广。

| [1] |

Lee SY. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol Bioeng, 1996, 49(1): 1-14. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960105)49:1<1::AID-BIT1>3.0.CO;2-P

|

| [2] |

Philip S, Keshavarz T, Roy I. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: biodegradable polymers with a range of applications. J Chem Technol Biot, 2010, 82(3): 233-247.

|

| [3] |

Zinn M, Witholt B, Egli T. Occurrence, synthesis and medical application of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate. Adv Drug Deliver Rev, 2001, 53(1): 5-21. DOI:10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00218-6

|

| [4] |

Gao X, Chen JC, Wu Q, et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoates as a source of chemicals, polymers, and biofuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2011, 22(6): 768-774. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2011.06.005

|

| [5] |

车雪梅, 司徒卫, 余柳松, 等. 聚羟基脂肪酸酯的应用展望. 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(10): 1531-1542. Che XM, Situ W, Yu LS, et al. Application perspectives of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Chin J Biotech, 2018, 34(10): 1531-1542 (in Chinese). |

| [6] |

Sudesh K, Abe H, Doi Y. Synthesis, structure and properties of polyhydroxyalkanoates: Biological polyesters. Prog Polym Sci, 2000, 25(10): 1503-1555. DOI:10.1016/S0079-6700(00)00035-6

|

| [7] |

Li ZB, Yang J, Loh XJ. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: opening doors for a sustainable future. NPG Asia Mater, 2016, 8(4): e265. DOI:10.1038/am.2016.48

|

| [8] |

Lu JN, Tappel RC, Nomura CT. Mini-review: biosynthesis of poly (hydroxyalkanoates). Polym Rev, 2009, 49(3): 226-248. DOI:10.1080/15583720903048243

|

| [9] |

Meng DC, Shen R, Yao H, et al. Engineering the diversity of polyesters. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2014, 29: 24-33. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.02.013

|

| [10] |

Chen GQ, Hajnal I, Wu H, et al. Engineering biosynthesis mechanisms for diversifying polyhydroxyalkanoates. Trends Biotechnol, 2015, 33(10): 565-574. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.07.007

|

| [11] |

Li ZB, Loh XJ. Water soluble polyhydroxyalkanoates: future materials for therapeutic applications. Chem Soc Rev, 2015, 44(10): 2865-2879. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00089K

|

| [12] |

Ma YM, Wei DX, Yao H, et al. Synthesis, characterization and application of thermoresponsive polyhydroxyalkanoate-graft- poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). Biomacromolecules, 2016, 17(8): 2680-2690. DOI:10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00724

|

| [13] |

Yao H, Wei DX, Che XM, et al. Comb-like temperature-responsive polyhydroxyalkanoate-graft- poly(2-dimethylamino-ethylmethacrylate) for controllable protein adsorption. Polym Chem, 2016, 7(38): 5957-5965. DOI:10.1039/C6PY01235C

|

| [14] |

Yu LP, Zhang X, Wei DX, et al. Highly efficient fluorescent material based on rare-earth-modified polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biomacromolecules, 2019, 20(9): 3233-3241. DOI:10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01722

|

| [15] |

Kim DY, Kim HW, Chung MG, et al. Biosynthesis, modification, and biodegradation of bacterial medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates. J Microbiol, 2007, 45(2): 87-97.

|

| [16] |

Verlinden RAJ, Hill DJ, Kenward MA, et al. Bacterial synthesis of biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoates. J Appl Microbiol, 2010, 102(6): 1437-1449.

|

| [17] |

李正军, 魏晓星, 陈国强. 生产聚羟基脂肪酸酯的微生物细胞工厂. 生物工程学报, 2010, 26(10): 1426-1435. Li ZJ, Wei XX, Chen GQ. Microbial cell factories for production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Chin J Biotech, 2010, 26(10): 1426-1435 (in Chinese). |

| [18] |

Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol, 2014, 32(4): 347-355. DOI:10.1038/nbt.2842

|

| [19] |

Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas Ⅲ CF. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol, 2013, 31(7): 397-405. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004

|

| [20] |

Li LX, Piatek MJ, Atef A, et al. Rapid and highly efficient construction of TALE-based transcriptional regulators and nucleases for genome modification. Plant Mol Biol, 2014, 78(4/5): 407-416.

|

| [21] |

Coffey A, Ross RP. Bacteriophage-resistance systems in dairy starter strains: molecular analysis to application. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 2002, 82(1/2): 303-321.

|

| [22] |

Jansen R, Van Embden JD, Gaastra W. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol, 2002, 43(6): 1565-1575. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x

|

| [23] |

Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science, 2007, 315(5819): 1709-1712. DOI:10.1126/science.1138140

|

| [24] |

Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in Staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science, 2008, 322(5909): 1843-1845. DOI:10.1126/science.1165771

|

| [25] |

Lv L, Ren YL, Chen JC, et al. Application of CRISPRi for prokaryotic metabolic engineering involving multiple genes, a case study: Controllable P(3HB-co-4HB) biosynthesis. Metab Eng, 2015, 29: 160-168. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.013

|

| [26] |

Li D, Lv L, Chen JC, et al. Controlling microbial PHB synthesis via CRISPRi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017, 101(14): 5861-5867. DOI:10.1007/s00253-017-8374-6

|

| [27] |

Jung HR, Yang SY, Moon YM, et al. Construction of efficient platform Escherichia coli strains for polyhydroxyalkanoate production by engineering branched pathway. Polymers, 2019, 11(3): 509. DOI:10.3390/polym11030509

|

| [28] |

Macrae RM, Wilkinson JF. Poly-β-hyroxybutyrate metabolism in washed suspensions of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus megaterium. J Gen Microbiol, 1958, 19(1): 210-222. DOI:10.1099/00221287-19-1-210

|

| [29] |

Chowdhury AA. Poly-β-hydroxybuttersäure abbauende Bakterien und Exoenzym. Archiv Mikrobiol, 1963, 47(2): 167-200. DOI:10.1007/BF00422523

|

| [30] |

Merrick JM, Doudoroff M. Depolymerization of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate by an intracellular enzyme system. J Bacteriol, 1964, 88(1): 60-71. DOI:10.1128/JB.88.1.60-71.1964

|

| [31] |

Delafield FP, Doudoroff M, Palleroni NJ, et al. Decomposition of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate by Pseudomonads. J Bacteriol, 1965, 90(5): 1455-1466. DOI:10.1128/JB.90.5.1455-1466.1965

|

| [32] |

Steinbüchel A, Valentin HE. Diversity of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 1995, 128(3): 219-228. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07528.x

|

| [33] |

Schubert P, Steinbüchel A, Schlegel HG. Cloning of the Alcaligenes eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly-beta-hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol, 1988, 170(12): 5837-5847.

|

| [34] |

Peoples OP, Sinskey AJ. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene (phbC). J Biol Chem, 1989, 264(2): 15298-15303.

|

| [35] |

Sim SJ, Snell KD, Hogan SA, et al. PHA synthase activity controls the molecular weight and polydispersity of polyhydroxybutyrate in vivo. Nat Biotechnol, 1997, 15(1): 63-67. DOI:10.1038/nbt0197-63

|

| [36] |

Kim J, Kim YJ, Choi SY, et al. Crystal structure of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase C-terminal domain and reaction mechanisms. Biotechnol J, 2017, 12(1): 1600648. DOI:10.1002/biot.201600648

|

| [37] |

Kim YJ, Choi SY, Kim J, et al. Structure and function of the N-terminal domain of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase, and the proposed structure and mechanisms of the whole enzyme. Biotechnol J, 2016, 12(1): 1600649.

|

| [38] |

Wittenborn EC, Jost M, Wei YF, et al. Structure of the catalytic domain of the class Ⅰ polyhydroxybutyrate synthase from Cupriavidus necator. J Biol Chem, 2016, 291(48): 25264-25277. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M116.756833

|

| [39] |

Amara A, Steinbüchel A, Rehm B. In vivo evolution of the Aeromonas punctata polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase: isolation and characterization of modified PHA synthases with enhanced activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2002, 59(4/5): 477-482.

|

| [40] |

Nomura CT, Taguchi S. PHA synthase engineering toward superbiocatalysts for custom-made biopolymers. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2007, 73(5): 969-979. DOI:10.1007/s00253-006-0566-4

|

| [41] |

Sujatha K, Mahalakshmi A, Solaiman DKY, et al. Sequence analysis, structure prediction, and functional validation of phaC1/phaC2 genes of Pseudomonas sp. LDC-25 and its importance in polyhydroxyalkanoate accumulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2009, 26(6): 771-779. DOI:10.1080/07391102.2009.10507289

|

| [42] |

Takase T, Matsumoto K, Taguchi S, et al. Alteration of substrate chain-length specificity of type Ⅱ synthase for polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by in vitro evolution: in vivo and in vitro enzyme assays. Biomacromolecules, 2004, 5(2): 480-485. DOI:10.1021/bm034323+

|

| [43] |

Matsumoto K, Takase K, Aoki E, et al. Synergistic effects of Glu130Asp substitution in the type Ⅱ polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase: enhancement of PHA production and alteration of polymer molecular weight. Biomacromolecules, 2005, 6(1): 99-104. DOI:10.1021/bm049650b

|

| [44] |

Matsumoto K, Aoki E, Takase K, et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of Ser477X mutations in polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase 1 from Pseudomonas sp. 61−3: effects of beneficial mutations on enzymatic activity, substrate specificity, and molecular weight of PHA. Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7(8): 2436-2442. DOI:10.1021/bm0602029

|

| [45] |

Yin J, Wang H, Fu XZ, et al. Effects of chromosomal gene copy number and locations on polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis by Escherichia coli and Halomonas sp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2015, 99(13): 5523-5534. DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-6510-8

|

| [46] |

Zhao H, Zhang HM, Chen XB, et al. Novel T7-like expression systems used for Halomonas. Metab Eng, 2017, 39: 128-140. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2016.11.007

|

| [47] |

Acuña JMBD, Bielecka A, Häussler S, et al. Production of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate in metabolic flux optimized Pseudomonas putida. Microb Cell Fact, 2014, 13: 88. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-13-88

|

| [48] |

Poblete-Castro I, Binger D, Rodrigues A, et al. In-silico-driven metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for enhanced production of poly-hydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng, 2013, 15: 113-123. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.004

|

| [49] |

Choi JI, Lee SY. Process analysis and economic evaluation for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by fermentation. Bioprocess Eng, 1997, 17(6): 335-342. DOI:10.1007/s004490050394

|

| [50] |

Slater SC, Voige WH, Dennis DE. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway. J Bacteriol, 1988, 170(10): 4431-4436. DOI:10.1128/JB.170.10.4431-4436.1988

|

| [51] |

Wang F, Lee SY. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) by fed-batch culture of filamentation-suppressed recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1997, 63(12): 4765-4769. DOI:10.1128/AEM.63.12.4765-4769.1997

|

| [52] |

Kahar P, Tsuge T, Taguchi K, et al. High yield production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from soybean oil by Ralstonia eutropha and its recombinant strain. Polym Degrad Stab, 2004, 83(1): 79-86. DOI:10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00227-1

|

| [53] |

Park SJ, Ahn WS, Green PR, Lee, et al. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate- co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strains. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2001, 74(1): 82-87. DOI:10.1002/bit.1097

|

| [54] |

Purama RK, Al-Sabahi JN, Sudesh K. Evaluation of date seed oil and date molasses as novel carbon sources for the production of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) by Cupriavidus necator H16 Re 2058/pCB113. Ind Crop Prod, 2018, 119: 83-92. DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.04.013

|

| [55] |

Bhatia SK, Yoon JJ, Kim HJ, et al. Engineering of artificial microbial consortia of Ralstonia eutropha and Bacillus subtilis for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co- 3-hydroxyvalerate) copolymer production from sugarcane sugar without precursor feeding. Bioresour Technol, 2018, 257: 92-101. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.056

|

| [56] |

Leaf TA, Peterson MS, Stoup SK, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing bacterial polyhydroxybutyrate synthase produces poly-3-hydroxybutyrate. Microbiology, 1996, 142(5): 1169-1180. DOI:10.1099/13500872-142-5-1169

|

| [57] |

Poirier Y, Dennis DE, Klomparens K, et al. Polyhydroxybutyrate, a biodegradable thermoplastic, produced in transgenic plants. Science, 1992, 256(5056): 520-523. DOI:10.1126/science.256.5056.520

|

| [58] |

Marangoni C, Furigo A Jr, De Aragão GMF. Production of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3- hydroxyvalerate) by Ralstonia eutropha in whey and inverted sugar with propionic acid feeding. Process Biochem, 2002, 38(2): 137-141. DOI:10.1016/S0032-9592(01)00313-2

|

| [59] |

Koller M, Hesse P, Bona R, et al. Potential of various archae- and eubacterial strains as industrial polyhydroxyalkanoate producers from whey. Macromol Biosci, 2007, 7(2): 218-226. DOI:10.1002/mabi.200600211

|

| [60] |

Aldor IS, Kim SW, Prather KLJ, et al. Metabolic engineering of a novel propionate-independent pathway for the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) in recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2002, 68(8): 3848-3854. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.8.3848-3854.2002

|

| [61] |

Yang JE, Choi YJ, Lee SJ, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2014, 98(1): 95-104. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5285-z

|

| [62] |

Haywood GW, Anderson AJ, Williams DR, et al. Accumulation of a poly(hydroxyalkanoate) copolymer containing primarily 3-hydroxyvalerate from simple carbohydrate substrates by Rhodococcus sp. NCIMB 40126. Int J Biol Macromol, 1991, 13(2): 83-88. DOI:10.1016/0141-8130(91)90053-W

|

| [63] |

Doi Y, Kanesawa Y, Kunioka M, et al. Biodegradation of microbial copolyesters: poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate). Macromolecules, 1990, 23(1): 26-31. DOI:10.1021/ma00203a006

|

| [64] |

Valentin HE, Dennis D. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) in recombinant Escherichia coli grown on glucose. J Biotechnol, 1997, 58(1): 33-38. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1656(97)00127-2

|

| [65] |

Li ZJ, Shi ZY, Jian J, et al. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) from unrelated carbon sources by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Metab Eng, 2010, 12(4): 352-359. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2010.03.003

|

| [66] |

Park SJ, Jang YA, Noh W, et al. Metabolic engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from sucrose. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2014, 112(3): 638-643.

|

| [67] |

Santimano MC, Prabhu NN, Garg S. PHA production using low-cost agro-industrial wastes by Bacillus sp. strain COL1/A6.. Res J Microbiol, 2009, 4(3): 89-96. DOI:10.3923/jm.2009.89.96

|

| [68] |

Sheu DS, Chen WM, Yang JY, et al. Thermophilic bacterium Caldimonas taiwanensis produces poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) from starch and valerate as carbon sources. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2009, 44(5): 289-294. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2009.01.004

|

| [69] |

Sukruansuwan V, Napathorn SC. Use of agro-industrial residue from the canned pineapple industry for polyhydroxybutyrate production by Cupriavidus necator strain A-04. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2018, 11: 202. DOI:10.1186/s13068-018-1207-8

|

| [70] |

Park SJ, Park JP, Lee SY. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) from whey by fed-batch culture of recombinant Escherichia coli in a pilot-scale fermenter. Biotechnol Lett, 2002, 24(3): 185-189. DOI:10.1023/A:1014196906095

|

| [71] |

Rodriguez-Perez S, Serrano A, Pantión AA, et al. Challenges of scaling-up PHA production from waste streams. A review. J Environ Manage, 2018, 205: 215-230.

|

| [72] |

Scott D, Brannan J, Higgins IJ. The effect of growth conditions on intracytoplasmic membranes and methane mono-oxygenase activities in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Microbiology, 1981, 125(1): 63-72. DOI:10.1099/00221287-125-1-63

|

| [73] |

Brigham C. Perspectives for the biotechnological production of biofuels from CO2 and H2 using Ralstonia eutropha and other 'Knallgas' bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019, 103(5): 2113-2120. DOI:10.1007/s00253-019-09636-y

|

| [74] |

Miyake M, Takase K, Narato M, et al. Polyhydroxybutyrate production from carbon dioxide by Cyanobacteria. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2000, 84: 991-1002.

|

| [75] |

Andreeßen B, Lange AB, Robenek H, et al. Conversion of glycerol to poly(3-hydroxypropionate) in recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2010, 76(2): 622-626. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02097-09

|

| [76] |

Sánchez RJ, Schripsema J, Da Silva LF, et al. Medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoic acids (PHAmcl) produced by Pseudomonas putida IPT 046 from renewable sources. Eur Polym J, 2003, 39(7): 1385-1394. DOI:10.1016/S0014-3057(03)00019-3

|

| [77] |

Kroumova AB, Wagner GJ, Davies HM. Biochemical observations on medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis and accumulation in Pseudomonas mendocina. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2002, 405(1): 95-103. DOI:10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00350-8

|

| [78] |

Cavalheiro JMBT, Raposo RS, De Almeida MCMD, et al. Effect of cultivation parameters on the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4- hydroxybutyrate) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-4- hydroxybutyrate-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Cupriavidus necator using waste glycerol. Bioresour Technol, 2012, 111: 391-397. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.176

|

| [79] |

Doi Y, Segawa A, Kunioka M. Biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) produced from γ-butyrolactone and butyric acid by Alcaligenes eutrophus. Polym Commun, 1989, 30(6): 169-171.

|

| [80] |

Kobayashi G, Shiotani T, Shima Y, et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from oils and fats by Aeromonas sp. OL-338 and Aeromonas sp. FA440. Stud Polym Sci, 1994, 12: 410-416.

|

| [81] |

Lu XY, Zhang JY, Wu Q, et al. Enhanced production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) via manipulating the fatty acid β-oxidation pathway in E. coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2020, 221(1): 97-101.

|

| [82] |

Chung AL, Jin HL, Huang LJ, et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly (3-hydroxydodecanoate) by β-oxidation inhibited mutant of Pseudomonas entomophila L48. Biomacromolecules, 2011, 12(10): 3559-3566. DOI:10.1021/bm200770m

|

| [83] |

Wang HH, Li XT, Chen GQ. Production and characterization of homopolymer polyhydroxyheptanoate (P3HHp) by a fadBA knockout mutant Pseudomonas putida KTOY06 derived from P. Putida KT2442. Process Biochem, 2009, 44(1): 106-111. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2008.09.014

|

| [84] |

Chen GQ, Jiang XR. Engineering bacteria for enhanced polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) biosynthesis. Synth Syst Biotechnol, 2017, 2(3): 192-197. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2017.09.001

|

| [85] |

Liu Q, Luo G, Zhou XR, et al. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxydecanoate) and 3-hydroxydodecanoate dominating polyhydroxyalkanoates by β-oxidation pathway inhibited Pseudomonas putida. Metab Eng, 2010, 13(1): 11-17.

|

| [86] |

Qi QS, Steinbüchel A, Rehm BHA. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 1998, 167(1): 89-94.

|

| [87] |

Tripathi L, Wu LP, Meng DC, et al. Pseudomonas putida KT2442 as a platform for the biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates with adjustable monomer contents and compositions. Bioresour Technol, 2013, 142: 225-231. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.027

|

| [88] |

Tripathi L, Wu LP, Chen JC, et al. Synthesis of diblock copolymer poly-3-hydroxybutyrate -block- poly-3-hydroxyhexanoate[PHB-b-PHHx] by a β-oxidation weakened Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Microb Cell Fact, 11: 44. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-11-44

|

| [89] |

Li MY, Chen XB, Che XM, et al. Engineering Pseudomonas entomophila for synthesis of copolymers with defined fractions of 3-hydroxybutyrate and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng, 2018, 52: 253-262.

|

| [90] |

Green PR, Kemper J, Schechtman L, et al. Formation of short chain length/medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate copolymers by fatty acid β-oxidation inhibited Ralstoniaeutropha. Biomacromolecules, 2002, 3(1): 208-213. DOI:10.1021/bm015620m

|

| [91] |

Ward PG, O'Connor KE. Bacterial synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates containing aromatic and aliphatic monomers by Pseudomonas putida CA-3. Int J Biol Macromol, 2005, 35(3/4): 127-133.

|

| [92] |

Choi SY, Park SJ, Kim WJ, et al. One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol, 2016, 34(4): 435-440. DOI:10.1038/nbt.3485

|

| [93] |

Park SJ, Lee TW, Lim SC, et al. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates containing 2-hydroxybutyrate from unrelated carbon source by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2012, 93(1): 273-283. DOI:10.1007/s00253-011-3530-x

|

| [94] |

Yang JE, Kim JW, Oh YH, et al. Biosynthesis of poly(2-hydroxyisovalerate-co-lactate) by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol J, 2016, 11(12): 1572-1585. DOI:10.1002/biot.201600420

|

| [95] |

David Y, Joo JC, Yang JE, et al. Biosynthesis of 2-hydroxyacid-containing polyhydroxyalkanoates by employing butyryl-CoA transferases in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol J, 2017, 12(11). DOI:10.1002/biot.201700116

|

| [96] |

Li ZJ, Qiao KJ, Che XM, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the synthesis of the quadripolymer poly(glycolate-co-lactate-co-3- hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) from glucose. Metab Eng, 2017, 44: 38-44. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.09.003

|

| [97] |

Yang JE, Park SJ, Kim WJ, et al. One-step fermentative production of aromatic polyesters from glucose by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strains. Nat Commun, 2018, 9: 79. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02498-w

|

| [98] |

Mizuno S, Enda Y, Saika A, et al. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates containing 2-hydroxy-4- methylvalerate and 2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropionate units from a related or unrelated carbon source. J Biosci Bioeng, 2018, 125(3): 295-300. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.10.010

|

| [99] |

Jiang XR, Wang H, Shen R, et al. Engineering the bacterial shapes for enhanced inclusion bodies accumulation. Metab Eng, 2015, 29: 227-237. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.017

|

| [100] |

Shen R, Ning ZY, Lan YX, et al. Manipulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granular sizes in Halomonas bluephagenesis. Metab Eng, 2019, 54: 117-126. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.011

|

| [101] |

Wang Y, Wu H, Jiang XR, et al. Engineering Escherichia coli for enhanced production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) in larger cellular space. Metab Eng, 2014, 25: 183-193. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2014.07.010

|

| [102] |

Jiang XR, Chen GQ. Morphology engineering of bacteria for bio-production. Biotechnol Adv, 2015, 34(4): 435-440.

|

| [103] |

Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring. J Bacteriol, 1993, 175(4): 1118-1125. DOI:10.1128/JB.175.4.1118-1125.1993

|

| [104] |

van Den Ent F, Amos LA, Löwe J. Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton. Nature, 2001, 413(6851): 39-44. DOI:10.1038/35092500

|

| [105] |

Graumann PL. Cytoskeletal elements in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol, 2004, 7(6): 565-571. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2004.10.010

|

| [106] |

Tan D, Wu Q, Chen JC, et al. Engineering Halomonas TD01 for the low-cost production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng, 2014, 26: 34-47. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2014.09.001

|

| [107] |

Ummalyma SB, Gnansounou E, Sukumaran RK, et al. Bioflocculation: An alternative strategy for harvesting of microalgae—An overview. Bioresour Technol, 2017, 242: 227-235. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.02.097

|

| [108] |

Bauer FF, Govender P, Bester MC. Yeast flocculation and its biotechnological relevance. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2010, 88(1): 31-39. DOI:10.1007/s00253-010-2783-0

|

| [109] |

Ling C, Qiao GQ, Shuai BW, et al. Engineering self-flocculating Halomonas campaniensis for wastewaterless open and continuous fermentation. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2018, 116(4): 805-815.

|

| [110] |

Yue HT, Ling C, Yang T, et al. A seawater-based open and continuous process for polyhydroxyalkanoates production by recombinant Halomonas campaniensis LS21 grown in mixed substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2014, 7: 108. DOI:10.1186/1754-6834-7-108

|

| [111] |

Tan D, Xue YS, Aibaidula G, et al. Unsterile and continuous production of polyhydroxybutyrate by Halomonas TD01. Bioresour Technol, 2011, 102(17): 8130-8136. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.05.068

|

| [112] |

Mahansaria R, Dhara A, Saha A, et al. Production enhancement and characterization of the polyhydroxyalkanoate produced by Natrinema ajinwuensis (as synonym) ≡ Natrinema altunense strain RM-G10. Int J Biol Macromol, 2018, 107: 1480-1490. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.009

|

| [113] |

Liu Y, Huang SB, Zhang YQ, et al. Isolation and characterization of a thermophilic Bacillus shackletonii K5 from a biotrickling filter for the production of polyhydroxybutyrate. J Environ Sci, 2014, 26(7): 1453-1462. DOI:10.1016/j.jes.2014.05.011

|

| [114] |

Qin Q, Ling C, Zhao YQ, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing genome of extremophile Halomonas spp. Metab Eng, 2018, 47: 219-229. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.018

|

| [115] |

Ling C, Qiao GQ, Shuai BW, et al. Engineering NADH/NAD+ ratio in Halomonas bluephagenesis for enhanced production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). Metab Eng, 2018, 49: 275-286. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.09.007

|

| [116] |

Ye JW, Hu DK, Che XM, et al. Engineering of Halomonas bluephagenesis for low cost production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) from glucose. Metab Eng, 2018, 47: 143-152. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.013

|

| [117] |

Quillaguamán J, Guzmán H, Van-Thuoc D, et al. Synthesis and production of polyhydroxyalkanoates by halophiles: current potential and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2010, 85(6): 1687-1696. DOI:10.1007/s00253-009-2397-6

|

| [118] |

Mahler N, Tschirren S, Pflügl S, et al. Optimized bioreactor setup for scale-up studies of extreme halophilic cultures. Biochem Eng J, 2018, 130: 39-46. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2017.11.006

|

| [119] |

Valdez-Cruz NA, Caspeta L, Pérez NO, et al. Production of recombinant proteins in E. coli by the heat inducible expression system based on the phage lambda pL and/or pR promoters. Microb Cell Fact, 2010, 9: 18. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-9-18

|

| [120] |

Müller K, Engesser R, Metzger S, et al. A red/far-red light-responsive bi-stable toggle switch to control gene expression in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(7): e77. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkt002

|

| [121] |

Yin X, Shin HD, Li JH, et al. P gas, a low-pH-induced promoter, as a tool for dynamic control of gene expression for metabolic engineering of Aspergillus niger. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2017, 83(6): e03222-16.

|

| [122] |

Khosla C, Curtis JE, Bydalek P, et al. Expression of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli using an oxygen-responsive promoter. Nat Biotechnol, 1990, 8(6): 554-558. DOI:10.1038/nbt0690-554

|

2021, Vol. 37

2021, Vol. 37