糖苷酶耐热性改造策略与应用

刘蕊

,

柳雨

,

李巧峰

,

冯旭东

,

李春

,

高小朋

生物工程学报  2021, Vol. 37 2021, Vol. 37 Issue (6): 1919-1930 Issue (6): 1919-1930

|

糖苷酶,又称糖苷水解酶,是可以对各种糖苷键进行水解的一类酶(EC 3.2.1.X),广泛存在于动物、植物和微生物细胞中[1-3],参与生物体内相关糖的代谢,生成一系列具有高附加值的糖及其衍生物[4]。糖苷酶催化水解糖苷键的过程一般需要通过两个催化氨基酸(通常为谷氨酸或天冬氨酸) 进行催化:其中一个是亲核试剂,另一个是酸/碱质子对。根据糖苷化合物中异头碳是否发生构象改变可将糖苷酶的催化机制分为两种:保留型机制(图 1A) 和反转型机制(图 1B)[5]。由于糖苷酶可催化并生成具有更高附加值的产物,因而广泛应用于食品[6]、医药[7]领域,除此之外,糖苷酶在能源[8]、纸浆[9]等领域的重要性也备受关注。工业领域应用的糖苷酶一般需在高温条件下进行催化,因此,市场对耐高温的高性能糖苷酶的需求逐年增加。

糖苷酶作为生物催化剂,在催化效率、底物特异性、环境友好等方面具有明显优势,但在实际应用中,很多天然的中温糖苷酶面对生产过程中较高的温度时,其催化活性和稳定性明显降低、甚至会丧失活性,严重影响催化效率,无法满足工业生产的长效需求。例如在纸浆漂白、酿酒和能源转换等工业生产中都需要维持高温生产来降低生物质粘度、提高反应体系均一性、加速反应过程并降低污染风险[10],而大多数糖苷酶的最适温度在40 ℃左右,难以有效发挥作用,所以获得在高温环境下具有良好催化活性的糖苷酶就显得尤为必要[11]。目前,具有耐热性能的糖苷酶的获得主要有两个途径:直接从不同耐热微生物体内挖掘耐热糖苷酶,如从嗜热链球菌TC11中挖掘出的α葡萄糖苷酶、从嗜热脂肪土芽孢杆菌中挖掘的木聚糖酶等[12-13];通过蛋白质改造技术提高中温糖苷酶的专一性和耐热性。

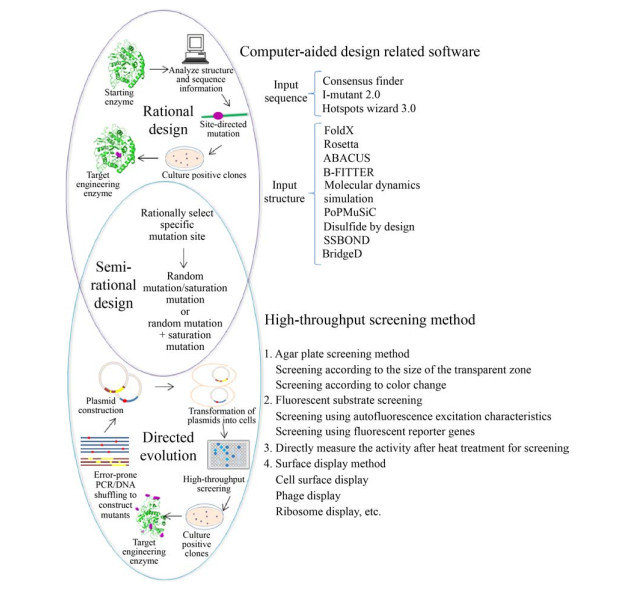

蛋白质改造技术是一种结合了分子生物学、蛋白质晶体学、生物化学、计算机科学等的多学科技术,可用于大多数酶分子的改造,从而满足工业化生产需求[14]。分子生物学的快速发展推动了蛋白质改造技术的升级,同时,随着对蛋白质结构和功能认识的逐步深入,蛋白质的从头设计成为了解决蛋白质结构和功能问题的新兴方法之一[15]。总而言之,蛋白质改造技术为按需改造蛋白质结构和功能提供了可能,并为工业化应用提供了多种催化效率更高的酶源。目前,从生物角度来看,蛋白质改造技术主要以定向进化、理性设计和半理性设计3种策略应用居多(图 2)。本文对近年来利用这3种策略改造糖苷酶耐热性的研究进展与应用进行综述,比较不同策略之间的优势和不足,并对未来糖苷酶耐热性的改造方向进行展望。

|

| 图 2 糖苷酶耐热性改造流程图 Fig. 2 Procedure for engineering the thermo-stability of glycosidase. |

| |

1993年美国科学家Arnold首次提出酶定向进化的概念并应用于天然酶的改造,此后,蛋白质的定向进化得以广泛应用[16]。定向进化,不需要已知蛋白质结构和作用机制,仅通过模拟自然进化过程(随机突变、重组和选择),使基因发生大量变异来构建突变体库,并进一步结合高通量筛选方法筛选出具有预期特性突变酶[17]。定向进化有两个关键环节:一个是产生随机突变,创建尽可能大的随机突变体库,以DNA改组技术为代表的有性进化和以易错PCR技术为代表的无性进化是最常用的产生随机突变的方法;另一个是开发高效快捷的高通量筛选方法。

易错PCR法是利用PCR过程中出现的碱基错配,对特定基因进行随机诱变的技术,是糖苷酶定向改造研究中常用到的随机突变方法之一。目前,市面上众多的突变试剂盒均能实现定向进化突变体库的构建,是三维结构还未解析的糖苷酶分子耐热性改造的有力工具。Sürmeli等[18]对硫化土杆菌来源的GH51家族α-L-阿拉伯呋喃糖酶进行定向进化,用一轮易错PCR,结合酶催化特异性底物对硝基苯基α-L-阿拉伯呋喃糖苷水解产生的透明圈大小进行筛选,从73个突变体中筛选出2个透明圈最大的优良突变体,最终突变体在71 ℃的热稳定性较野生型提高30%。于越[19]运用相同的方法对α-L-鼠李糖苷酶构建随机突变库,借助96孔板从3 000多个突变体中筛选出了5株热稳定性提高的突变体。为了构建更加完备的突变体库,获得更接近预期的突变体,通常需要进行多轮进化或结合多种突变方法。Li等[20]运用两轮定向进化策略(先进行一轮易错PCR,再进行一轮DNA改组),结合刚果红平板筛选以及活性测定,得到了一株替换3个氨基酸(Y233H、L264M和N343S) 的β-甘露聚糖酶组合突变体,突变体的最适温度提高了10 ℃,且表现出了良好的热稳定性。采用同样的组合定向进化策略,Ruller等[21]筛选出了80 ℃半衰期提高60 min的木聚糖酶突变体。

由于定向进化的突变体库容量大都在103之上,为了获得优良的耐热突变体,高效的高通量筛选体系非常关键。根据酶和底物反应的催化特性,开发一种简单、高效的筛选技术有助于提高筛选通量、快速锁定理想突变。近年来,虽不断有新的筛选方法涌出,但常用的方法依旧能满足大多数突变体的筛选:Liu等报道的脂酶与三丁酸甘油酯水解后在琼脂糖平板上形成的透明圈大小筛选阳性克隆的琼脂平板筛选技术[22];Zhou等通过测定α-葡萄糖苷酶与对硝基苯基-β-D-吡喃葡萄糖苷(4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside,pNPG) 反应后释放的对硝基苯酚在410 nm处光吸收值来筛选阳性克隆的分光光度法[23];Fan等利用谷氨酸脱羧酶在pH指示剂溴甲酚绿作用下向亮蓝变色的反应筛选阳性突变体的颜色反应法[24];Goedegebuur等直接将检测葡聚糖酶用高温孵育后的活性保留量作为筛选阳性克隆的活性测定法[25];此外,一些表面展示技术也为高效的筛选提供了可能[26]。

随着X射线晶体衍射技术的发展,越来越多的蛋白质获得了晶体结构解析,通过分析蛋白质结构来改造特定位点且省时省力的理性设计方法越来越受到青睐[27]。

2 基于蛋白质结构与分子动力学模拟分析的理性设计与定点突变理性设计是在对蛋白质的序列信息、三维结构、作用机制等有一定了解的基础上,对确定的位点进行突变来找寻优良突变体的方法。目前利用理性设计提高酶耐热性的研究大多从以下3个方面展开。

2.1 同源序列比对,分析潜在突变位点中温酶和耐热糖苷酶的氨基酸序列同源比对可挖掘到与耐热性相关的保守氨基酸或者序列,作为潜在突变位点[28]。具有相同保守氨基酸的酶被认为是具有共同的进化关系,在同源序列比对中,增加比对的耐热酶数量,可能得到更多影响酶耐热性的潜在突变位点。Han等[29]通过将GH11家族木聚糖XynCDBFV和NCBI数据库中同家族的所有木聚糖酶序列进行比对,发现87-RGHT-90这段序列在大多数木聚糖酶中表现得相对保守,结合B-factor分析,该酶C末端的氨基酸序列87-QNSS-90的B-factor值较高,因此对相应位点进行氨基酸突变,得到的突变体N88G在65 ℃耐热性提高了60%。同样也是从保守序列入手,Feng等[30]将大肠杆菌表达的β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶PGUS与和其高度同源的CAZY数据库中20个同家族嗜热糖苷酶进行序列比对,找到8个潜在突变位点,最终获得突变体F292L/T293K PGUS在65 ℃的耐热性提高了30%。序列比对可以单独作为一种策略来设计耐热性突变体,但更多情况下,需要结合理性的结构分析以及其他算法支持,共同实现酶耐热性的改造提升[31]。

2.2 通过结构分析确定潜在突变位点酶分子的结构稳定性对酶的耐热性起着重要作用,通过增加酶分子的相互作用力、增强酶分子结构刚性、降低其柔性结构、引入分子伴侣蛋白、糖基化和引入二硫键等方法有助于不同程度地提高酶分子耐热性。

在糖苷酶的耐热性研究中,精氨酸的引入使得耐热性的提高体现出一定的优势,由于精氨酸侧链的胍基可以在不同方向发生相互作用,比其他氨基酸能形成更多的相互作用力,因此精氨酸一直是设计耐热突变的热点氨基酸[32]。Kaewpathomsri等[33]通过分析GH77家族的淀粉麦芽糖酶结构,将远离活性中心的27位点谷氨酸突变为精氨酸,使其在酶分子表面形成了一个精氨酸簇(R27-R30-R31-R34),增强了糖苷酶表面的相互作用力,最终使得突变体在80 ℃时的活性较野生型提高了40%。精氨酸在糖苷酶的耐碱性改造中也发挥着巨大作用[34]。此外,甘氨酸具有最高的构象熵,因此甘氨酸突变可以降低展开熵,从而稳定糖苷酶结构;脯氨酸在侧链上有一个环状结构(吡咯烷环) 使其具有独特的构象刚性,引入脯氨酸有利于提高糖苷酶分子的结构稳定性,对提高耐热性也发挥着巨大作用[35-36]。

在糖苷酶改造工程中,仅对部分氨基酸进行取代的“小改”对酶分子耐热性的提升大多是有限的,往往需要对酶分子进行“中改”,比如将糖苷酶分子部分结构域进行截除、替换或者引入其他结构域或伴侣蛋白。其中,通过截除柔性区域是“中改”最常见的方式之一。酶结构中的柔性区域通常被认为是影响酶结构稳定性的关键部分[37],而柔性区域大多集中在结构的末端以及无规则卷曲中,所以该区域的截除或截短有可能实现酶耐热性的提升[38]。Han等[39]通过动力学模拟发现,GH2家族β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶PGUS的C末端柔性较大,截除C末端14个氨基酸后,突变体在70 ℃的耐热性提高了30%左右;该课题组Feng等[40]用两个耐热酶的稳定无规则卷曲序列替换了PGUS-E的相应柔性序列(图 3),替换后的突变酶在70 ℃的半衰期较出发酶提高了11.8倍[40]。

|

| 图 3 β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶PGUS-E的柔性区域(A:PGUS-E四聚体结构,蓝色球形为催化位点;B:PGUS-E整体柔性展示颜色越红,线条越粗,柔性越大,则刚性越小,结构越不稳定;C–D:部分loop环的局部图[40]) Fig. 3 The flexible region of β-glucuronidase PGUS-E. (A) The structure of PGUS-E tetramer. The catalytic sites are shown in blue spheres. (B) Flexible display of PGUS-E. Unstable regions with greater flexibility and lower rigidity are shown in thick lines and red color. (C–D) Partial view of part of loop ring[40]. |

| |

N-糖基化可以影响酶的热稳定性。对未经修饰的酶分子定量引入糖基化位点,有可能实现酶耐热性的提升;而对高度糖基化的酶,通过部分去糖基化,也可以提高酶的耐热性[41]。王小艳等[42]对毕赤酵母重组表达的β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶结构表面loop/turn区的3个目标序列进行人工糖基化位点设计,最终在65 ℃下,N-糖基化后的突变体较野生酶活性提高了10%左右。这些研究都不同程度证明了适度的糖基化对酶的热稳定性具有正向作用。

除此之外,在蛋白结构内部引入二硫键也能提高酶的热稳定性。Tang等[43]在里氏木霉菌来源的GH11家族木聚糖酶的N末端与α螺旋到β片层核心处引入2对二硫键,使突变体在60 ℃下的半衰期提高了2.5倍。Yang等[44]对沙生梭孢壳菌来源的GH45家族纤维素酶结构分析,通过在该酶分子内部引入二硫键后,酶在100 ℃的活性提升了15%左右。二硫键的引入对酶耐热性提升有一定作用,但引入二硫键数目过多时可能出现二硫键成键不完全的现象,所以在设计二硫键时,需考虑周围氨基酸对二硫键成键的影响。

2.3 计算机辅助设计,找寻潜在突变位点计算机辅助的蛋白质设计是指利用计算机算法或软件,对已知序列、结构和功能信息的蛋白质作相应的数据分析处理,最终确定潜在突变位点。

目前,针对蛋白质热稳定性设计的软件层出不穷,对理性设计突变位点带来了诸多便利,研究者们也纷纷将其应用到不同的糖苷酶上,并得到了较好的效果[45]。Torktaz等[46]利用PoPMuSiC软件在线预测了GH5家族的糖苷酶Cel5,用非极性的色氨酸替换了位于活性位点附近94位点的极性天冬酰胺,扩大了疏水口袋,使得突变体在60 ℃的热稳定较野生型提高150%。根据不同能量状态与蛋白质稳定性的关系也可以用于突变位点的确定。Bu等[47]借助FoldX、Rosetta_ddg、ABACUS这3个计算机算法初步选取了木聚糖酶中折叠自由能较小的位点(图 4),并结合分子动力学模拟剔除了其中不合理的突变,进一步实验验证得到了10个显著影响酶耐热性的潜在突变位点,组合后的优良突变体在65 ℃的热稳定性较野生型提高了60%。此外,分子动力学模拟也可进行突变位点的预测。Li等对[48]细菌来源的嗜中温GH11家族木聚糖酶进行分子动力学模拟,结合B-factor值分析发现木聚糖酶N末端41个氨基酸与同源嗜热酶的N末端42个氨基酸进行替换后,RMSD值降低,木聚糖酶稳定性得以提高,替换后的突变体较野生型在60 ℃的半衰期延长了28 min。

半理性设计结合了定向进化和理性设计的优点,将突变限制到一个或几个位点之上,可以在较小的库容量中得到好的突变体。一般包括两个步骤:1) 通过蛋白质序列、结构和功能信息以及计算机算法等预判潜在的目标位点;2) 对目标位点进行定向进化或饱和突变,进而筛选具有期望特性的突变体。

通过分析糖苷酶结构的B-factor可以指示酶的柔性区域,B-factor值越大,柔性越强,以此作为突变依据,通过提高柔性区域的刚性,进而实现糖苷酶耐热性提升[49]。Li等[50]对GH11家族木聚糖酶进行分子动力学模拟,选择B-factor较高的21位点甘氨酸进行饱和突变,得到的突变体G21I半衰期较野生型提高了11.8倍。同样,除了根据特征参数选取潜在突变位点外,对分子的氨基酸序列和结构信息的分析,也可获得影响酶耐热性的潜在突变位点。Xu等[51]利用软件分析了几丁质酶的序列和结构,发现S244和I319可形成二硫键且S259位点可能影响酶的耐热性,因此额外设计二硫键并对259位点饱和突变后,突变体在50 ℃的半衰期较野生型提高了26.3倍。随着计算机软件和算法的发展,基于酶结构分析的计算机辅助设计为改造酶的耐热性提供了极大便利。Song等[52]通过计算机辅助分析黑曲霉来源的GH10家族木聚糖酶,确定了5个氨基酸位点并进行了4轮迭代饱和突变,最终得到的五突变体(R25W/V29A/I31L/L43F/T58I) 在60 ℃的半衰期较野生型延长了60倍。

4 不同策略改造糖苷酶耐热性的比较不同蛋白质改造策略提高糖苷酶的耐热性的实例见表 1。由表 1可知,定向进化广泛应用于糖苷酶特性改造,具体用哪种策略取决于对酶的认识和对策略的解读。定向进化的突变体库容量一般较大,需要高效的筛选方法。对于还未解析结构的酶来说,查找公共数据库中已被鉴定和注释的同源耐热酶序列,或借用可分析序列的软件可以得到有关信息。而对于具有晶体结构的糖苷酶,从关键位点出发,通过构建小的突变体库来筛选优良突变的半理性设计极大地减少了工作量,这是相对高效的改造方法。由于改造糖苷酶稳定性的方法通常费时费力,所以利用计算技术辅助预测酶的功能和活性成为近年来改造糖苷酶的新选择。

| Echnology | Enzyme (Resource) | Strategy | Result (Compare with the starting enzyme) | Pros and cons | References |

| Directed evolution | α-L-rhamnosidase (Aspergillus niger JMU-TS528) | Error-prone PCR | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 60 ℃ is doubled | Pros: no restriction of enzyme structure Cons: the mutant library is large and screening is difficult |

[53] |

| α-glucosidase (Thermus thermophilus TC11) | Error-prone PCR | The thermostable mutant is almost activity loss when incubate at 70 ℃ for 7 h | [23] | ||

| Xylanase (Geobacillus stearothermophilus) | Error-prone PCR and family DNA shuffling | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 75 ℃ is 52 times that of the wild type | [54] | ||

| β-glucuronidase (Penicillium purpurogenum Li-3) | Error-prone PCR | The activity of the thermostable mutant increased by 10% when treated at 65 ℃ for 120 min | [55] | ||

| Rational design | Xylanase (Aspergillus oryzae) | N-terminal sequence replacement | The thermostable mutant still retains 85% of the initial activity when treated at 60 ℃ for 100 min | Pros: fast point selection and high accuracy Cons: may miss the best mutant |

[56] |

| Endoglucanase (Penicillium verruculosum) | Sequence alignment and free energy calculation | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 80 ℃ increased by 1.3 times | [57] | ||

| β-glucuronidase (Aspergillus terreus Li-20) | C-terminal non-conservative gene sequence editing | The thermostable mutant was treated at 65 ℃ for 30 min, and retained 30% of the initial activity higher than that of the wild type | [58] | ||

| β-glucuronidase (Aspergillus oryzae Li-3) | Design sugar bridges and sugar clips | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 70 ℃ is 7.1 times that of the wild type | [59] | ||

| Chitosanase (Bacillus ehimensis) | Artificially designed disulfide bonds | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 50 ℃ is 58.8 min longer than that of the wild type | [60] | ||

| Xylanase (Talaromyces leycettanus JCM12802) | Structure-based N-terminal modification | The dissolution temperature of the thermostable mutant is 7.8 ℃ higher than that of the starting enzyme | [61] | ||

| β-mannanase (Bacillus subtilis TJ-102) | Molecular dynamics simulation | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 60 ℃ is 24 times that of the wild type | [62] | ||

| β-mannanase (Aspergillus usamii) | Computer-assisted protein fusion | The temperature required to maintain the same residual activity increased by 8 ℃ | [63] | ||

| Pullulanase (Bacillus acidopullulyticus) | PoPMuSiC-2.1 Software-aided prediction | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 60 ℃ is 11 times that of the wild type | [64] | ||

| Semirational design | Xylanase (Psychrobacter sp. strain 2-17) | Error-prone PCR and saturation mutation | The half-inactivation temperature of the thermostable mutant increased by 4.3 ℃ | Pros: the small mutant library is not easy to miss good mutants Cons: it is still necessary to construct a mutant library through experiments |

[65] |

| Endoglucanase (Clostridium thermocellum) | Structural analysis and saturation mutation | The thermostable mutant has a 10-fold increase in the half-life at 86 ℃ | [66] | ||

| β-glycosidase (Thermus thermophiles) | Structure and sequence analysis, saturation mutation | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 93 ℃ increased by 4.7 times | [67] | ||

| β-glucuronidase (Talaromyces pinophilum Li-93) | Random mutation and the introduction of arginine on the TIM barrel | The half-life of the thermostable mutant at 55 ℃ increased by 2.9 times | [68] |

随着糖苷键水解产生的重要衍生物被广泛应用,糖苷酶的工业应用价值受关注。然而,由于大多天然中温糖苷酶在工业高温条件下活性较低,直接从耐热生物体内挖掘可工业应用的嗜热酶又并非易事,所以蛋白质改造技术是目前最温和有效的方法[69]。

除此之外,晶体结构的解析对于快速精准地改造糖苷酶分子结构、提升糖苷酶的耐热性也是非常关键的。但是对一些晶体结构解析较为困难的糖苷酶,除了了解酶的氨基酸序列信息外,使用定向进化、同源建模和序列比对来确定突变位点是最常用的改造策略。在未来蛋白质改造中,电镜技术和蛋白质晶体学的快速发展会让越来越多的糖苷酶分子结构得到解析,为快速高效提升糖苷酶的催化特性提供了坚实的理论基础。针对酶分子的氨基酸序列特性,开发更精确的结构和功能预测软件,有望实现通过糖苷酶的序列分析计算对酶进行更准确的突变位点预测。同时,开发更精确的计算机辅助蛋白质修饰也将是未来蛋白质耐热性改造的一大趋势。

| [1] |

Chen JJ, Liang X, Chen TJ, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of a β-glycoside hydrolase from Lentinula edodes. Molecules, 2019, 24(1): 59.

|

| [2] |

Fusco FA, Fiorentino G, Pedone E, et al. Biochemical characterization of a novel thermostable β-glucosidase from Dictyoglomus turgidum. Int J Biol Macromol, 2018, 113: 783-791. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.018

|

| [3] |

Espinoza K, Eyzaguirre J. Identification, heterologous expression and characterization of a novel glycoside hydrolase family 30 xylanase from the fungus Penicillium purpurogenum. Carbohyd Res, 2018, 468: 45-50. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2018.08.006

|

| [4] |

Xu YH, Feng XD, Jia JT, et al. A novel β-glucuronidase from Talaromyces pinophilus Li-93 precisely hydrolyzes glycyrrhizin into glycyrrhetinic acid 3-O-mono-β-D-glucuronide. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2018, 84(19): e00755-18.

|

| [5] |

Honda Y, Kitaoka M. The first glycosynthase derived from an inverting glycoside hydrolase. J Biol Chem, 2006, 281(3): 1426-1431. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M511202200

|

| [6] |

Zhang Y, He SD, Simpson B K. Enzymes in food bioprocessing — novel food enzymes, applications, and related techniques. Curr Opin Food Sci, 2018, 19(2): 30-35.

|

| [7] |

Fleming D, Rumbaugh KP. Approaches to dispersing medical biofilms. Microorganisms, 2017, 5(2): 15. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms5020015

|

| [8] |

Dodd D, Cann IKO. Enzymatic deconstruction of xylan for biofuel production. Glob Change Biol Bioenergy, 2009, 1(1): 2-17. DOI:10.1111/j.1757-1707.2009.01004.x

|

| [9] |

Kumar V, Marín-Navarro J, Shukla P. Thermostable microbial xylanases for pulp and paper industries: trends, applications and further perspectives. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 32(2): 34. DOI:10.1007/s11274-015-2005-0

|

| [10] |

Tian YS, Xu J, Chen L, et al. Improvement of the thermostability of xylanase from Thermobacillus composti through site-directed mutagenesis. J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017, 27(10): 1783-1789. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1705.05026

|

| [11] |

Lee YR, Jung S, Chi WJ, et al. Biochemical characterization of a novel GH86 β-agarase producing neoagarohexaose from Gayadomonas joobiniege G7. J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 28(2): 284-292. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1710.10011

|

| [12] |

Yun BY, Jun SY, Kim NA, et al. Crystal structure and thermostability of a putative α-glucosidase from Thermotoga neapolitana. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2011, 416(1/2): 92-98.

|

| [13] |

Lo Leggio L, Kalogiannis S, Bhat MK, et al. High resolution structure and sequence of T. aurantiacus xylanase Ⅰ: implications for the evolution of thermostability in family 10 xylanases and enzymes with βα-barrel architecture. Proteins, 2015, 36(3): 295-306.

|

| [14] |

Alan F, Greg W. Protein engineering. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 1992, 17(8): 292-294. DOI:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90438-F

|

| [15] |

Boyken SE, Benhaim MA, Busch F, et al. De novo design of tunable, pH-driven conformational changes. Science, 2019, 364(6441): 658-664. DOI:10.1126/science.aav7897

|

| [16] |

Chen K, Arnold FH. Tuning the activity of an enzyme for unusual environments: sequential random mutagenesis of subtilisin E for catalysis in dimethylformamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1993, 90(12): 5618-5622. DOI:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5618

|

| [17] |

Powell KA, Ramer SW, Del Cardayré SB, et al. Directed evolution and biocatalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2001, 40(21): 3948-3959. DOI:10.1002/1521-3773(20011105)40:21<3948::AID-ANIE3948>3.0.CO;2-N

|

| [18] |

Sürmeli Y, İlgü H, Şanlı-Mohamed G, et al. Improved activity of α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Geobacillus vulcani GS90 by directed evolution: investigation on thermal and alkaline stability. Biotechnol Appl Biochem, 2019, 66(1): 101-107. DOI:10.1002/bab.1702

|

| [19] |

于越. 黑曲霉α-L-鼠李糖苷酶热稳定性定向进化的研究[D]. 厦门: 集美大学, 2016. Yu Y. Researches about the thermostability directedevolution of Aspergillus niger α-L-rhamnosidase[D]. Xiamen: Jimei University, 2016 (in Chinese). |

| [20] |

Li YX, Yi P, Yan QJ, et al. Directed evolution of a β-mannanase from Rhizomucor miehei to improve catalytic activity in acidic and thermophilic conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2017, 10: 143. DOI:10.1186/s13068-017-0833-x

|

| [21] |

Ruller R, Alponti J, Deliberto LA, et al. Concommitant adaptation of a GH11 xylanase by directed evolution to create an alkali-tolerant/ thermophilic enzyme. Prot Eng Des Select, 2014, 27(8): 255-262. DOI:10.1093/protein/gzu027

|

| [22] |

Liu XL, Liang MJ, Liu YH, et al. Directed evolution and secretory expression of a pyrethroid- hydrolyzing esterase with enhanced catalytic activity and thermostability. Microb Cell Fact, 2017, 16(1): 81. DOI:10.1186/s12934-017-0698-5

|

| [23] |

Zhou C, Xue YF, Ma YH. Evaluation and directed evolution for thermostability improvement of a GH13 thermostable α-glucosidase from Thermus thermophilus TC11. BMC Biotechnol, 2015, 15: 97. DOI:10.1186/s12896-015-0197-x

|

| [24] |

Fan LQ, Li MW, Qiu YJ, et al. Increasing thermal stability of glutamate decarboxylase from Escherichia. coli by site-directed saturation mutagenesis and its application in GABA production. J Biotechnol, 2018, 278: 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.04.009

|

| [25] |

Goedegebuur F, Dankmeyer L, Gualfetti P, et al. Improving the thermal stability of cellobiohydrolase Cel7A from Hypocrea jecorina by directed evolution. J Biol Chem, 2017, 292(42): 17418-17430. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M117.803270

|

| [26] |

Traxlmayr MW, Shusta EV. Directed evolution of protein thermal stability using yeast surface display. Methods Mol Biol, 2017, 1575: 45-65.

|

| [27] |

Wijma HJ, Floor RJ, Janssen D B. Structure- and sequence-analysis inspired engineering of proteins for enhanced thermostability. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2013, 23(4): 588-594. DOI:10.1016/j.sbi.2013.04.008

|

| [28] |

Currin A, Swainston N, Day PJ, et al. Synthetic biology for the directed evolution of protein biocatalysts: navigating sequence space intelligently. Chem Soc Rev, 2015, 44(5): 1172-1239. DOI:10.1039/C4CS00351A

|

| [29] |

Han NY, Miao HB, Ding JM, et al. Improving the thermostability of a fungal GH11 xylanase via site-directed mutagenesis guided by sequence and structural analysis. Biotechnol Biofuels, 2017, 10: 133. DOI:10.1186/s13068-017-0824-y

|

| [30] |

Feng XD, Tang H, Han BJ, et al. Enhancing the thermostability of β-glucuronidase by rationally redesigning the catalytic domain based on sequence alignment strategy. Ind Eng Chem Res, 2016, 55(19): 5474-5483. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00535

|

| [31] |

Wu XY, Tian ZN, Jiang XK, et al. Enhancement in catalytic activity of Aspergillus niger XynB by selective site-directed mutagenesis of active site amino acids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 102(11): 249-260.

|

| [32] |

Li LJ, Liao H, Yang Y, et al. Improving the thermostability by introduction of arginines on the surface of α-L-rhamnosidase (r-Rha1) from Aspergillus niger. Int J Biol Macromol, 2018, 112: 14-21. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.078

|

| [33] |

Kaewpathomsri P, Takahashi Y, Nakamura S, et al. Characterization of amylomaltase from Thermus filiformis and the increase in alkaline and thermo-stability by E27R substitution. Proc Biochem, 2015, 50(11): 1814-1824. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2015.08.006

|

| [34] |

Li QF, Jiang T, Liu R, et al. Tuning the pH profile of β-glucuronidase by rational site-directed mutagenesis for efficient transformation of glycyrrhizin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019, 103(12): 4813-4823. DOI:10.1007/s00253-019-09790-3

|

| [35] |

Matthews BW, Nicholson H, Becktel WJ. Enhanced protein thermostability from site-directed mutations that decrease the entropy of unfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1987, 84(19): 6663-6667. DOI:10.1073/pnas.84.19.6663

|

| [36] |

Wang K, Luo HY, Tian J, et al. Thermostability improvement of a Streptomyces xylanase by introducing proline and glutamic acid residues. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014, 80(7): 2158-2165. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03458-13

|

| [37] |

Yu HR, Huang H. Engineering proteins for thermostability through rigidifying flexible sites. Biotechnol Adv, 2014, 32(2): 308-315. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.10.012

|

| [38] |

Li MC, Guo SY, Li XM, et al. Engineering a highly thermostable and stress tolerant superoxide dismutase by N-terminal modification and metal incorporation. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng, 2017, 22(6): 725-733. DOI:10.1007/s12257-017-0243-8

|

| [39] |

Han BJ, Hou YH, Jiang T, et al. Computation-aided rational deletion of C-terminal region improved the stability, activity, and expression level of GH2 β-glucuronidase. J Agric Food Chem, 2018, 66(43): 11380-11389. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03449

|

| [40] |

Feng XD, Tang H, Han BJ, et al. Engineering the thermostability of β-glucuronidase from penicillium purpurogenum Li-3 by loop transplant. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 100(23): 9955-9966. DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-7630-5

|

| [41] |

Takatsugu M, Hiroyuki Y, Atsushi N, et al. The side chain of a glycosylated asparagine residue is important for the stability of isopullulanase. J Biochem, 2015, 157(4): 225-234. DOI:10.1093/jb/mvu065

|

| [42] |

王小艳, 樊艳爽, 韩蓓佳, 等. 糖基化改造β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶的热稳定性. 化工学报, 2015, 66(9): 3669-3677. Wang XY, Fan YS, Han BJ, et al. Improvement of thermostability of recombinant β-glucuronidase by glycosylation. CIESC J, 2015, 66(9): 3669-3677 (in Chinese). |

| [43] |

Tang F, Chen DW, Yu B, et al. Improving the thermostability of Trichoderma reesei xylanase 2 by introducing disulfide bonds. Electr J Biotechnol, 2017, 26: 52-59. DOI:10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.01.001

|

| [44] |

Yang H, Zhang YQ, Li XX, et al. Impact of disulfide bonds on the folding and refolding capability of a novel thermostable GH45 cellulase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 102(21): 9183-9192. DOI:10.1007/s00253-018-9256-2

|

| [45] |

Musil M, Stourac J, Bendl J, et al. FireProt: web server for automated design of thermostable proteins. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017, 45(W1): W393-W399. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkx285

|

| [46] |

Torktaz I, Karkhane AA, Hemmat J. Rational engineering of Cel5E from Clostridium thermocellum to improve its thermal stability and catalytic activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 102(8): 8389-8402. DOI:10.1007/s00253-018-9204-1

|

| [47] |

Bu YF, Cui YL, Peng Y, et al. Engineering improved thermostability of the GH11 xylanase from Neocallimastix patriciarum via computational library design. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 102(3): 3675-3685.

|

| [48] |

Li C, Li JF, Wang R, et al. Substituting both the N-terminal and "cord" regions of a xylanase from Aspergillus oryzae to improve its temperature characteristics. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2018, 185(8): 1044-1059.

|

| [49] |

Sun ZT, Liu Q, Qu G, et al. Utility of B-factors in protein science: interpreting rigidity, flexibility, and internal motion and engineering thermostability. Chem Rev, 2019, 119(3): 1626-1665. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00290

|

| [50] |

Li XQ, Wu Q, Hu D, et al. Improving the temperature characteristics and catalytic efficiency of a mesophilic xylanase from Aspergillus oryzae, AoXyn11A, by iterative mutagenesis based on in silico design. AMB Express, 2017, 7(1): 97. DOI:10.1186/s13568-017-0399-9

|

| [51] |

Xu P, Ni ZF, Zong MH, et al. Improving the thermostability and activity of Paenibacillus pasadenensis chitinase through semi-rational design. Int J Biol Macromol, 2020, 150: 9-15. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.033

|

| [52] |

Song LT, Tsang A, Sylvestre M. Engineering a thermostable fungal GH10 xylanase, importance of N-terminal amino acids. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2015, 112(6): 1081-1091. DOI:10.1002/bit.25533

|

| [53] |

Li LJ, Wu ZY, Yu Y, et al. Development and characterization of an α-L-rhamnosidase mutant with improved thermostability and a higher efficiency for debittering orange Juice. Food Chem, 2018, 245: 1070-1078. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.064

|

| [54] |

Zhang ZG, Yi ZL, Pei XQ, et al. Improving the thermostability of Geobacillus stearothermophilus xylanase XT6 by directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis. Bioresour Technol, 2010, 101(23): 9272-9278. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.07.060

|

| [55] |

矫丽媛, 吕波, 王金娜, 等. 重组β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶转化甘草酸的定向性改造. 石河子大学学报(自然科学版), 2013, 31(5): 640-644. Jiao LY, Lü B, Wang JN, et al. Directly modified recombinant β-glucuronidase for glycyrrhizin transformation. J Shihezi Univ (Nat Sci), 2013, 31(5): 640-644 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-7383.2013.05.019 |

| [56] |

Yin X, Li JF, Wang JQ, et al. Enhanced thermostability of a mesophilic xylanase by N-terminal replacement designed by molecular dynamics simulation. J Sci Food Agric, 2013, 93(12): 3016-3023. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.6134

|

| [57] |

Dotsenko AS, Rozhkova AM, Zorov IN, et al. Protein surface engineering of endoglucanase Penicillium verruculosum for improvement in thermostability and stability in the presence of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid. Bioresour Technol, 2020, 296: 122370. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122370

|

| [58] |

Xu YH, Liu YL, Rasool A, et al. Sequence editing strategy for improving performance of β-glucuronidase from Aspergillus terreus. Chem Eng Sci, 2017, 167: 145-153. DOI:10.1016/j.ces.2017.04.011

|

| [59] |

Feng XD, Wang XY, Han BJ, et al. Design of glyco-linkers at multiple structural levels to modulate protein stability. J Phys Chem Lett, 2018, 9(16): 4638-4645. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b01570

|

| [60] |

Sheng J, Ji XF, Zheng Y, et al. Improvement in the thermostability of chitosanase from Bacillus ehimensis by introducing artificial disulfide bonds. Biotechnol Lett, 2016, 38(10): 1809-1815. DOI:10.1007/s10529-016-2168-2

|

| [61] |

Wang XY, Ma R, Xie XM, et al. Thermostability improvement of a Talaromyces leycettanus xylanase by rational protein engineering. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 15287. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-12659-y

|

| [62] |

Wang XC, You SP, Zhang JX, et al. Rational design of a thermophilic β-mannanase from Bacillus subtilis TJ-102 to improve its thermostability. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2018, 118: 50-56. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2018.07.005

|

| [63] |

Li JF, Wang CJ, Hu D, et al. Engineering a family 27 carbohydrate-binding module into an Aspergillus usamii β-mannanase to perfect its enzymatic properties. J Biosci Bioeng, 2017, 123(3): 294-299. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2016.09.009

|

| [64] |

Chen AN, Li YM, Nie JQ, et al. Protein engineering of Bacillus acidopullulyticus pullulanase for enhanced thermostability using in silico data driven rational design methods. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2015, 78: 74-83. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.06.013

|

| [65] |

Aceved JP, Reetz MT, Asenjo JA, et al. One-step combined focused epPCR and saturation mutagenesis for thermostability evolution of a new cold-active xylanase. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2017, 100: 60-70. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2017.02.005

|

| [66] |

Yi ZL, Pei XQ, Wu ZL. Introduction of glycine and proline residues onto protein surface increases the thermostability of endoglucanase CelA from Clostridium thermocellum. Bioresour Technol, 2011, 102(3): 3636-3638. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.043

|

| [67] |

Yi ZL, Zhang SB, Pei XQ, et al. Design of mutants for enhanced thermostability of β-glycosidase BglY from Thermus thermophilus. Bioresour Technol, 2013, 129: 629-633. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.098

|

| [68] |

Feng XD, Liu XF, Jia JT, et al. Enhancing the thermostability of β-glucuronidase from T. pinophilus enables the biotransformation of glycyrrhizin at elevated temperature. Chem Eng Sci, 2019, 204: 91-98. DOI:10.1016/j.ces.2019.04.020

|

| [69] |

朱国萍. 用蛋白质工程方法设计和改造工业用酶. 安徽师范大学学报(自然科学), 1998, 21(4): 402-405. Zhu GP. Design and reform of industrial enzymes by protein engineering. J Anhui Normal Univ (Nat Sci), 1998, 21(4): 402-405 (in Chinese). |