宏基因组及培养组学技术在粪菌移植中的应用

句英娇

,

王小通

,

王隐瑜

,

李翠丹

,

岳利亚

,

陈非

生物工程学报  2022, Vol. 38 2022, Vol. 38 Issue (10): 3594-3605 Issue (10): 3594-3605 |

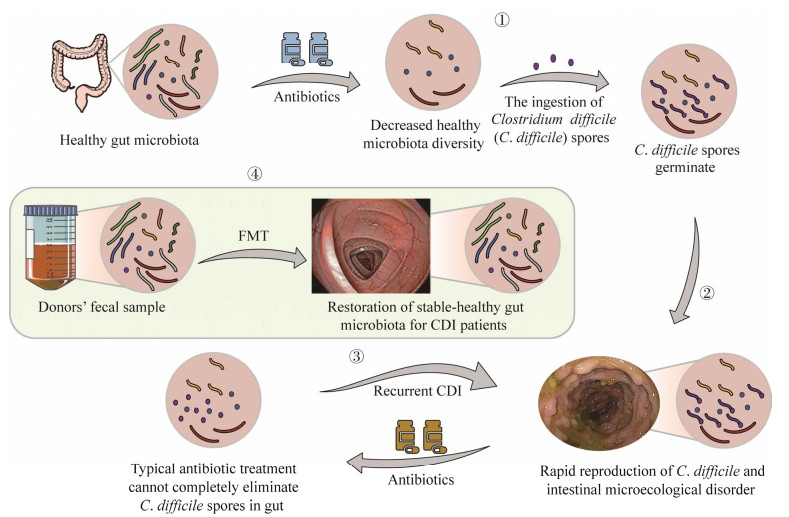

粪菌移植技术(fecal microbiota transplantation, FMT) 是利用健康人群肠道微生物(即粪便或经过处理的粪便) 来治疗消化、代谢等系统诸多疾病的一项技术。其最早的应用可追溯到我国东晋时期,其后在中国各朝代医药古籍都有报道,可用于治疗食物中毒、腹泻、发热并发濒临死亡等患者[1];进入现代医疗时代后,特别是在宏基因组出现之后,该技术得到了飞速的发展,目前其已逐步发展成为治疗艰难梭菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI) 所导致的严重肠炎的最后治疗手段(图 1),其在多种胃肠道消化系统疾病、代谢系统疾病、精神系统疾病和肿瘤免疫治疗等方面也得到了广泛的尝试和应用,往往获得意想不到的奇效[2]。

|

| 图 1 粪菌移植技术是应对艰难梭菌感染所致严重肠炎的“最后手段”[3] Fig. 1 Fecal microbiota transplantation is the "last resort" for treating Clostridium difficile infection[3]. ①抗生素的滥用降低了健康人肠道菌群的多样性,为艰难梭菌在肠道内的繁殖营造了环境;②艰难梭菌的迅速繁殖导致肠道微生态发生紊乱;③常规的抗生素治疗并不能完全杀灭肠道内的艰难梭菌的孢子,从而形成艰难梭菌反复感染(CDI);④粪便菌群移植:将健康供者的粪便引入CDI患者的肠道,可以有效治疗艰难梭菌的反复感染 ① Abuse of antibiotics decreases the diversity of healthy microbiota, producing an abnormal environment for rapid reproduction of C. difficile in the gut; ② Rapid reproduction of C. difficile leads to intestinal microecological disorder; ③ Recurrent C. difficile infection (CDI) because typical antibiotics treatment cannot completely eliminate CD spores in the gut; ④ Fecal microbiota transplantation: the stools from healthy donors are introduced into the guts of CDI patients. |

| |

尽管粪菌移植有诸多成功应用案例且被广泛报道,然而人体肠道菌群构成十分复杂,粪菌移植仍存在效果不稳定、异质性强、作用机理难以解释等问题。宏基因组技术可以全面地揭示健康及疾病状态下肠道微生态的组成及功能变化,而培养组学技术则可以尽可能多地从肠道样本中获得可培养的微生物,两项技术的联合使用不仅可以使我们更为深入地理解粪菌移植技术在临床实践中的因果规律,还将有力地推动粪菌移植技术在未来的应用与发展。基于此,本文综述了宏基因组及微生物培养组学技术在粪菌移植中的应用。

1 粪菌移植应用及其挑战粪菌移植,也叫“粪便移植” “粪菌治疗”或“肠微生态移植”,是将粪便物质的溶液从供体输送到受体的肠道中,直接改变受体的微生物组成以重塑患者的肠道菌群,实现肠道、代谢等多种类型疾病的治疗目标[4-5]。

最早将粪便用于治疗的是中国,东晋时期的葛洪(公元300−400年),在其所著《肘后备急方》中,记载了用粪清治疗食物中毒、腹泻、发热并濒临死亡的患者[6];李时珍《本草纲目》中描述了使用粪水或发酵粪便有效治疗20多种疾病的医疗实践案例[7]。进入现代医疗时代后,粪菌移植疗法最早于1958年被报道,美国外科医生Ben Eiseman及其同事使用粪液灌肠成功治疗一名严重伪膜性肠炎患者,这是FMT在国外文献中的最早记录[8]。进入21世纪,随着FMT技术的发展,有关FMT治疗各种疾病的成功案例报道越来越多。在美国,粪菌移植一直作为顽固性艰难梭菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI) 所致严重肠炎的最终极治疗手段,其治疗成功率高达90%[9]。尽管如此,考虑到安全性、美学、尊严等因素,很多患者、医生等仍对FMT持观望和消极态度。

2019年,我国张发明教授首次提出了洗涤菌群移植理论(washed microbiota transplantation, WMT),并发明了世界上第一套粪菌智能分离系统。WMT技术指的是基于智能系统的粪菌分离、漂洗、存储、移植和流程管理的整体过程[10]。相比于传统FMT,WMT在安全性上大大提高。2019年12月,我国专家经研讨达成了《洗涤菌群移植方法学南京共识》,该共识标准化了WMT的诸多流程[11],WMT的发明及标准化标志着粪菌移植技术迈向了新的阶段。

但是,随着FMT研究和应用的深入,FMT供体差异性等问题也逐渐呈现。研究者在治疗炎症性肠炎和代谢综合征的研究和实践中发现,仅有部分供体的粪便对患者起作用,即粪菌移植技术进行治疗时只有特定供体的粪菌才会有疗效。这说明粪菌移植过程中,可能是特定供体中的某些特殊菌群在发挥作用[12-13]。基于此,科学家们正致力于明确这些在粪便移植过程中起到关键作用的细菌或菌群组合。人体肠道有1013−1014个细菌[14-15],排除个体差异以定位这些起关键作用的特定肠道益生菌难度极大,而宏基因组学技术给我们提供了很好的武器来克服这一困难;与此同时,目前在肠道中已检出的微生物门类中,大部分为不可培养细菌,这给研究和确定特定肠道微生物的功能属性带来巨大困难,而培养组学为我们解决或部分解决上述问题提供了有效的手段和技术。

2 宏基因组技术精准解析粪菌移植肠道功能菌群结构及种类宏基因组,最初于1998年由Handelsman等提出,是指一个环境中全部微生物基因组信息,包含可培养的和不可培养的微生物物种,具体由细菌、真菌、病毒等组成,对人体肠道微生物而言,主要为细菌(99%以上)[16]。在20世纪80年代以前(一代测序技术产生之前),微生物的研究还没有组学的概念,通常是基于对可培养菌株分离培养的方式开展研究。当时,大多数的微生物是不可培养的,可培养菌株仅限于少数几种微生物[17]。进入21世纪,特别是近十年,宏基因组技术的出现和飞速发展,可以全景式地展示了环境(内环境与外环境) 微生态微生物的生存状态,特别是对一些无法/难培养及丰度低的微生物的揭示,极大地拓展了人们对微生态的认知。与传统微生物研究方法术相比,该技术具有通量大、价格低廉、准确性高、无需培养等诸多优势。

目前,微生物宏基因组测序技术又分为扩增子测序技术和鸟枪法全基因组(shotgun) 测序技术。对于细菌而言,扩增子测序技术即16S rRNA基因测序,主要用于微生物群落的物种组成及多样性研究,而shotgun全基因组测序技术则可以获得整个微生物群落的全部基因组信息,不仅可以研究群落的结构还可以研究其中各基因的功能[18]。

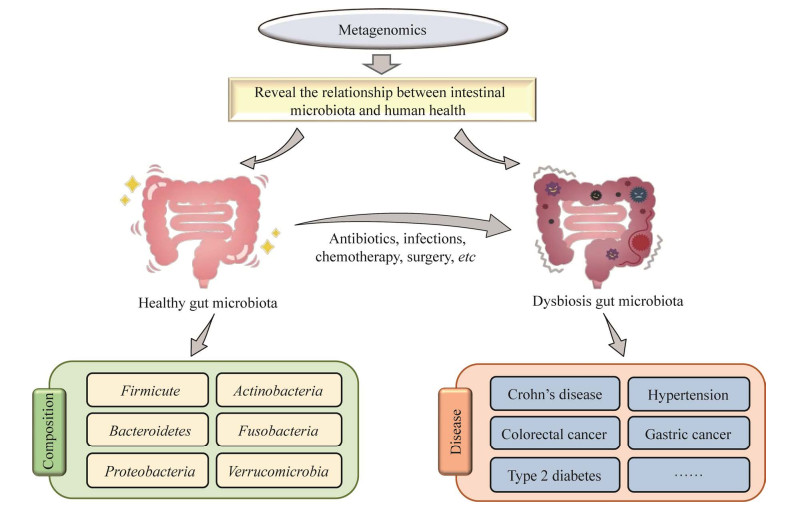

宏基因组研究可为粪菌移植提供较为完善的肠道菌群库信息(图 2)。对于人体而言,肠道微生物质量约1−1.5 kg,数量为1013−1014个,约是人体细胞数目的10倍。肠道微生物组成较为复杂,主要包括细菌、真菌、古菌、病毒和原虫[20-22]。依据目前宏基因组研究结果[23-24],人体肠道微生物菌群主要由约160种细菌主导,真菌、古菌、病毒等其他微生物较少,这些细菌归属于6个主要门类即:厚壁菌门、拟杆菌门、放线菌门、变形菌门、梭杆菌门和疣微菌门。拟杆菌/厚壁菌、变形菌/放线菌比值可以作为反映肠道“微生物健康”的指标:拟杆菌/厚壁菌、放线菌/变形菌比值越高越有利于肠道微生物健康[25]。

|

| 图 2 宏基因组为粪菌移植提供相对完整的人体微生物库信息[19] Fig. 2 Metagenomic analysis provides comprehensive human-microbiota information for fecal bacteria transplantation[19]. Metagenomic analysis reveals the relationship between intestinal microbiota and human health. The healthy gut microbiota is mainly composed of six dominated bacteria phyla, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrumicrobia. Many factors, such as abuse of antibiotics, infection, chemotherapy and surgery, may lead to the disequilibrium of intestinal microecosystem, further causing various diseases including Crohn's disease, hypertension, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, and type 2 diabetes. 宏基因组分析揭示了肠道菌群与人体健康的关系。健康的肠道菌群主要由6个占优势的细菌门组成,包括厚壁菌门、拟杆菌门、放线菌门、变形菌门、梭杆菌门和疣微菌门。许多因素(如抗生素滥用、感染、化疗、手术等) 会导致肠道微生态失衡,进而引起各种疾病(如克罗恩病、高血压、结直肠癌、胃癌、2型糖尿病等) |

| |

利用宏基因技术可揭示健康人群与各种疾病人群的肠道微生态组成和功能差异,Zhang等研究结果表明,帕金森患者的肠道微生物组成及多样性皆与健康配偶以及健康人不同,此外还鉴定到8个炎症相关的,且随着疾病持续时间的增加而增加的微生物属(副拟杆菌属(Parabacteroides)、阿克曼菌属(Akkermansia)、粪球菌属(Coprococcus)、嗜胆菌属(Bilophila)、柯林斯氏菌属(Collinsella)、甲烷短杆菌(Methanobrevibacter)、缓慢爱格士氏菌属(Eggerthella) 和阿德勒克罗伊茨菌属(Adlercreutzia)),这些菌可能是与帕金森恶化直接相关的特征性细菌[26]。宏基因组研究可以为FMT提供全方位、有效而精准地指导,包括FMT功能微生物的确定、FMT过程监控及机理分析、FMT健康供体的选择标准等。Bar-Yoseph等采用宏基因组学方法研究FMT技术根除产碳青霉烯霉肠杆菌科致病菌(Klebsiella) 的潜力,结果表明FMT成功者的微生物群落α和β多样性均出现显著变化,同时伴随着双歧杆菌(Bifidobacterium) 等益生菌含量的显著升高[27]。Chu等[28]使用宏基因组结合免疫球蛋白A (immunoglobulin A, IgA) 测序方法分析了来自12名接受粪便移植及安慰剂治疗的溃疡性结肠炎患者样本,发现了供体和患者菌株之间出现长时间、持续性的动态竞争。该研究同时确定了与炎症相关的细菌(拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)、毛螺菌科(Lachnospiraceae) 和瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)),并发现微生物与宿主免疫系统的相互作用可以在人之间转移。Fujimoto等[29]利用宏基因组学方法对9例成功进行FMT治疗的顽固性艰难梭菌感染患者及其供体人群肠道生物进行分析,结果表明噬菌体与其宿主细菌的协同作用恢复了受体的正常肠道菌群。Woodworth等[30]在总结了大量肠道微生物与特定疾病关联研究的基础之上,建议将2型糖尿病、既往心血管病患者(高血压、高血脂) 和频繁抗生素使用者排除在FMT的供体之外。

宏基因组扩充并加深了人类对肠道菌群生态的认识,我们不但可以从宏基因组测序数据中分析得到健康人的肠道微生态组成、各种疾病发生过程中肠道微生物组成和功能组成的变化,而且还可以对微生物与宿主、微生物与微生物之间相互作用的网络进行预测,从而进一步揭示微生物与宿主在肠道微生态系统中的功能关系,鉴定与肠道疾病相关的关键核心微生物功能菌群,最终指导靶向粪菌移植。然而,该技术在实践应用过程中依然存在很多问题,首先,即使较高的测序深度也无法实现对肠道中所有细菌物种的完整拼接复原,而越来越多的研究表明,即使是同一种菌,不同的菌株也会具有不同的功能[31];其次,很难组装出低丰度物种完整的基因组信息,事实上,一些在人类健康中起着重要作用的肠道微生物可能仅作为低丰度物种存在[32];第三,测序的分析技术受实验方案的影响较大,异质性强,提取DNA的方法、扩增的引物、测序深度或者生信分析的方法不同,均可能影响最终的结果[33-35];最后,该技术无法分辨群体中菌株的死活,从而无法真正客观地反映肠道微生物群落的功能[36]。为了准确地定位在粪菌移植过程中的核心功能微生物,分析微生物群落组成及其结构与特定疾病康复之间的关系,夯实宏基因组研究结果,我们还需发展可靠的、基于实验的微生物组学研究方法。培养组学(culturomics) 技术可以用来分离和鉴定人类肠道中的诸多在常规培养条件下未可培养菌——以便对这些菌展开功能研究和应用开发,这不仅可以有效弥补上述宏基因组技术在FMT应用中的种种不足,还可以更为精准地实现FMT的转化应用。

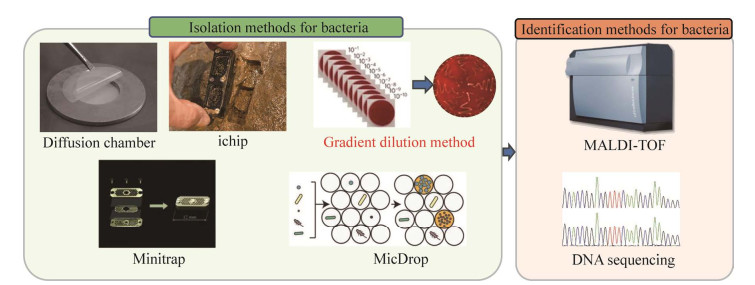

3 利用微生物培养组学技术分离肠道功能微生物培养组学是一种在多种培养条件下,通过高通量方式来进行细菌培养和筛选的方法(图 3),使用该技术可以尽可能多地获得在常规培养条件下未可培养微生物[42]。培养组学起源于环境微生物领域,环境微生物学家首先开发了模拟微生物自然环境的培养方法,例如,扩散室(diffusion chamber) 培养法和隔离芯片(isolation chip, ichip) 培养法。2007年,研究者通过在扩散室中培养环境样本,模拟细菌的自然环境以增加生长细菌的种类和数量[37],扩散室的两层膜允许环境养分而非细菌细胞进入,该技术可使培养菌落的数量增加了300倍[43]。后来,Nichols等设计了一种用于高通量细菌培养的隔离芯片,由数百个微型扩散室组成,每个扩散室接种一个环境细胞。这项技术证明,利用芯片获得的微生物种类超过传统培养方法的数倍,特别是δ-变形菌纲细菌[44]。此外,有研究者利用原核生物分泌的促生长因子共培养方法来促进目标微生物的培养[45]。

|

| 图 3 细菌培养组学的常规分离和鉴定方法(扩散室、隔离芯片、微陷阱富集、梯度稀释、MicDrop)[37-41] Fig. 3 Common culturomics methods for bacterial isolation and identification (diffusion-chamber, ichip, Minitrap, gradient-dilution and MicDrop)[37-41]. The gradient-dilution method is the most common approach in culturomics research. Both MALDI-TOF and DNA sequencing are extensively used in culturomics research for microbial identification. 梯度稀释涂布法是微生物培养组学研究中最常用的分离培养的方法MALDI-TOF和DNA测序是微生物培养组学研究中广泛应用的鉴定方法 |

| |

在临床微生物领域,对于人体微生物的培养最常用的传统方法是分离培养法。早在20世纪70年代,科学家就对肠道菌群进行了分离培养,累计获得了400多种不同的微生物物种[46]。对于肠道微生物的大规模分离培养,目前采用的方法包括传统的梯度稀释平板涂布法和基于微流控的单细胞分离培养方法[39, 47] (图 3)。传统的梯度稀释平板涂布法是最常用的大规模分离菌株方式。Zou等[47]从155名健康志愿者捐赠的新鲜粪便中,使用11种不同培养基在厌氧条件下,筛选得到了1 520株不同的分离株,且获得了高质量的基因组序列,最终确定了350种不同的菌种,包括149个新种、42个新属,扩展了肠道菌种基因组目录。Liu等[48]使用4种不同的培养基,在厌氧条件下,从小鼠肠道中分离得到了1 437株分离株,最终鉴定到了126个不同的物种,其中有77个新种。由于传统平板涂布法具有耗时耗力的缺陷,基于微流控高通量的分离培养方法的出现弥补了通量这一不足。Villa等[40]开发了一个细菌分离平台(MicDrop),该平台将微流控技术和高通量测序技术相结合,实现了在皮升级别大小的液滴中培养单个菌株,而且该技术获得的菌株的丰富度(richness) 是传统培养方法的2.8倍。Cross等还报道了一种使用基因组抗体将复杂群落中的特定微生物捕获到纯培养物中的方法,利用该方法成功分离和培养了难培养的人类口腔角藻属细菌TM7和未培养的物种口腔细菌SR1[49]。除了上述分离培养法外,富集培养法也应用较多,例如,2012年Sizova等扩充了可培养-人类口腔细菌库,研究人员同时利用体内口腔微生物微陷阱富集法(Minitrap)、平衡快生长影响的单细胞长期培养法、改进的常规富集法(不含糖的培养基) 等多种富集培养法筛选得到多种不同的口腔微生物[41]。

值得一提的是,目前我国的研究人员已经通过培养组技术构建了人肠道微生物资源库(hGMB:hgmb.nmdc.cn)。该研究通过培养我国健康志愿者提供的239份新鲜粪便样本组成的31份样本混合物,获得了10 558个分离物,并最终鉴定代表400个不同物种,1 170株菌株。这些资源保存在国际微生物保藏库(中国普通微生物菌种保藏管理中心(China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, CGMCC) 等) 中,以便在全球范围内长期保存和公众获取。hGMB代表了人类肠道中80%以上的微生物属和种,涵盖了50%的KEGG功能和10%的FUnkFams功能未知基因[50]。培养组学的研究扩展了人类肠道微生物资源菌库,尤其是增加了可培养肠道细菌数量。基于逐步完善的肠道微生物资源菌库,在未来,我们可以挖掘出更多新一代益生菌,建立与人体肠道疾病相关的细菌移植疗法,为推动和完善粪菌移植技术提供有力的资源支持。

宏基因组技术和培养组技术在FMT的发展中互为补充。未来,宏基因组技术可以进一步提供大量丰富的菌株信息、菌株互作信息、菌株与宿主互作信息,可以解析FMT的作用机理,还可以引导靶向功能菌筛选;培养组方面,我们可以整合更多的分离培养手段,利用宏基因组得到的信息,靶向筛选与分离更多的功能菌,一方面验证宏基因组的结果,另一方面,更加有力地推动FMT的发展—实现疾病特异的肠道细菌治疗目标。

4 益生菌组合配方是粪菌移植技术发展的必然趋势现有的研究数据可以在一定程度上证明FMT在治疗肠道、代谢性、精神炎等疾病的有效性,但是FMT的推广仍然任重而道远。首先,仍有FMT毒副作用(FMT传播的耐药菌血症的发生) 甚至死亡案例的报道[51-52];其次,粪菌成分组成复杂,研究表明只有特定供体中的某些特殊菌群在发挥作用,挖掘其中起关键作用的核心菌群变得非常有必要[53];最后,FMT的进行需要制定严格的给药和监管方案,过程繁杂,且从伦理、道德、心里等角度,并不利于大众接受[54]。而操纵益生菌特异性治疗或者改善疾病也是FMT发展的最终目标。因此具有特异疾病治疗特性的下一代益生菌组合配方的挖掘和利用是粪菌移植技术发展的必然趋势。宏基因组技术可以为FMT提供较为完善的肠道菌群库信息,靶向指导培养组对目标菌的筛选;培养组可以验证宏基因组获得的理论信息,扩充可培养的与人体肠道细菌疗法的功能菌库,加速益生菌产品的研发;二者相辅相成,共同助力下一代益生菌的挖掘与筛选,更好地服务于FMT的发展。

与传统益生菌相比,下一代益生菌属于尚未得到应用的肠道非典型益生菌[55]。随着宏基因组和培养组学技术在粪菌移植治疗疾病领域的广泛应用,一些对特定的疾病有显著治疗作用的大量的新型益生菌被揭示出来[56] (表 1),包括粪便普雷沃氏菌(Prevotella copri)[57-59]、嗜黏蛋白阿克曼氏菌(Akkermansia muciniphila)[55, 60-62]、脆弱拟杆菌(Bacteroides fragilis)[63-65]、普氏粪杆菌(Faecalibacterium prausnitzii)[66-68]、Christensenella minuta DSM33407[69]、Parabacteroides goldsteinii[55]、多形拟杆菌(Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron)[70-72]、难闻杆菌J115T (Dysosmobacter welbionis J115T)[73]、蜂房哈夫尼亚菌HA4597™ (Hafnia alvei HA4597™)[74-75]、解木聚糖拟杆菌(Bacteroides xylanisolvens)[76]以及吉氏副拟杆菌(Parabacteroides distasonis)[77]等。但是,毋庸讳言,这些益生菌有些属于条件致病菌,具有潜在的危害性,真正普及用于临床实践还需要大量临床试验的证实。宏基因组、培养组等肠道微生物组的研究技术为粪菌移植治疗疾病及益生菌组合配方挖掘,提供了强有力的研究和临床实践武器,助力我们另辟蹊径,走出别样健康发展之路。

| Next generation probiotics | Main characteristics | Functions | References |

| Prevotella copri | Improve glucose homeostasis by producing succinate; but aggravate glucose intolerance by augmenting circulating levels of (branched-chain amino acids) BCAAs | Succinate (a TCA cycle intermediate) production; Circulating serum levels of BCAAs increasement | [57-59] |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Improve metabolic disorders and obesity, reduce chronic inflammation and fat mass gain | Protein Amuc_1100; P9; propionate | [55, 60-62] |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Prevent Clostridium difficile infection in a mouse model by restoring gut barrier and microbiome regulation | A capsular polysaccharide PSA may enrich CD4+FoxP3 T cells after plasmacytoid DC cells presentation | [63-65] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Antiinflammation; Counterbalancing dysbiosis and repair tissue damage | Butyrate production | [66-68] |

| Christensenella minuta DSM33407 | Anti-obesity | Butyrate production | [69] |

| Parabacteroides goldsteinii | Ameliorates prediabetes syndromes and liver inflammations | Enhanced production of Treg and IL-10 | [55] |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Modulate host hepatic metabolism and ameliorate hepatic steatosis | Sphingolipid synthesis and acetate production | [70-72] |

| Dysosmobacter welbionis J115T | Prevent diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders in mice | Increased number of mitochondria but the exact mechanisms of action remain to be deciphered | [73] |

| Hafnia alvei HA4597™ | Anti-obesity | Peptide ClpB production | [74-75] |

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | Alleviate nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis in mice | Folate synthesis production | [76] |

| Parabacteroides distasonis | Decrease weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hepatic steatosis in mice | Succinate and secondary bile acids production | [77] |

| [1] |

Dodin M, Katz DE. Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection. Int J Clin Pract, 2014, 68(3): 363-368. DOI:10.1111/ijcp.12320

|

| [2] |

Zhang YT, Zhang J, Pan ZY, et al. Effects of washed fecal bacteria transplantation in sleep quality, stool features and autism symptomatology: a Chinese preliminary observational study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2022, 18: 1165-1173. DOI:10.2147/NDT.S355233

|

| [3] |

Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 9(2): 88-96.

|

| [4] |

Bakken JS, Borody T, Brandt LJ, et al. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 9(12): 1044-1049. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.014

|

| [5] |

Smits LP, Bouter KEC, De Vos WM, et al. Therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology, 2013, 145(5): 946-953. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.058

|

| [6] |

Shi YC, Yang YS. Fecal microbiota transplantation: current status and challenges in China. JGH Open, 2018, 2(4): 114-116. DOI:10.1002/jgh3.12071

|

| [7] |

Bakker GJ, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation: therapeutic potential for a multitude of diseases beyond clostridium difficile. Microbiol Spectr, 2017, 5(4): 5.4.19. DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0008-2017

|

| [8] |

Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, et al. Fecal Enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery, 1958, 44(5): 854-859.

|

| [9] |

Bakken JS. Fecal bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Anaerobe, 2009, 15(6): 285-289. DOI:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.09.007

|

| [10] |

Zhang FM, Cui BT, He XX, et al. Microbiota transplantation: concept, methodology and strategy for its modernization. Protein Cell, 2018, 9(5): 462-473. DOI:10.1007/s13238-018-0541-8

|

| [11] |

Shi Q. Nanjing consensus on methodology of washed microbiota transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl), 2020, 133(19): 2330-2332. DOI:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000954

|

| [12] |

Weingarden A, González A, Vázquez-Baeza Y, et al. Dynamic changes in short- and long-term bacterial composition following fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Microbiome, 2015, 3(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1186/s40168-014-0066-1

|

| [13] |

Bibbò S, Settanni CR, Porcari S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: screening and selection to choose the optimal donor. J Clin Med, 2020, 9(6): 1757. DOI:10.3390/jcm9061757

|

| [14] |

Power SE, O'Toole PW, Stanton C, et al. Intestinal microbiota, diet and health. Br J Nutr, 2014, 111(3): 387-402. DOI:10.1017/S0007114513002560

|

| [15] |

Wardman JF, Bains RK, Rahfeld P, et al. Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2022, 20(9): 542-556. DOI:10.1038/s41579-022-00712-1

|

| [16] |

Handelsman J, Rondon MR, Brady SF, et al. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chem Biol, 1998, 5(10): R245-R249. DOI:10.1016/S1074-5521(98)90108-9

|

| [17] |

Lu ZY. Microbiota research: from history to advances. E3S Web Conf, 2020, 145: 1-6. DOI:10.1051/e3sconf/202014500001

|

| [18] |

Riesenfeld CS, Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Metagenomics: genomic analysis of microbial communities. Annu Rev Genet, 2004, 38: 525-552. DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091216

|

| [19] |

Jackson MA, Verdi S, Maxan ME, et al. Gut microbiota associations with common diseases and prescription medications in a population-based cohort. Nature communications, 2018, 9(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02088-w

|

| [20] |

Dinan K, Dinan T. Antibiotics and mental health: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Intern Med, 2022, 00: 1-12.

|

| [21] |

Costea PI, Hildebrand F, Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes in the landscape of gut microbial community composition. Nat Microbiol, 2018, 3(1): 8-16. DOI:10.1038/s41564-017-0072-8

|

| [22] |

Matijašić M, Meštrović T, Paljetak HČ, et al. Gut microbiota beyond bacteria-mycobiome, virome, archaeome, and eukaryotic parasites in IBD. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(8): 2668. DOI:10.3390/ijms21082668

|

| [23] |

RodrÍguez JM, Murphy K, Stanton C, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Heal Dis, 2015, 26(1): 26050.

|

| [24] |

Huang JH, Liao JW, Fang Y, et al. Six-week exercise training with dietary restriction improves central hemodynamics associated with altered gut microbiota in adolescents with obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020, 11: 569085. DOI:10.3389/fendo.2020.569085

|

| [25] |

Trakman GL, Fehily S, Basnayake C, et al. Diet and gut microbiome in gastrointestinal disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 37(2): 237-245. DOI:10.1111/jgh.15728

|

| [26] |

Zhang F, Yue LY, Fang X, et al. Altered gut microbiota in Parkinson's disease patients/healthy spouses and its association with clinical features. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2020, 81: 84-88. DOI:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.10.034

|

| [27] |

Bar-Yoseph H, Carasso S, Shklar S, et al. Oral capsulized fecal microbiota transplantation for eradication of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization with a metagenomic perspective. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 73(1): e166-e175. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa737

|

| [28] |

Chu ND, Crothers JW, Nguyen LTT, et al. Dynamic colonization of microbes and their functions after fecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease. mBio, 2021, 12(4): e0097521. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00975-21

|

| [29] |

Fujimoto K, Kimura Y, Allegretti JR, et al. Functional restoration of bacteriomes and viromes by fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology, 2021, 160(6): 2089-2102.e12. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.013

|

| [30] |

Woodworth MH, Carpentieri C, Sitchenko KL, et al. Challenges in fecal donor selection and screening for fecal microbiota transplantation: a review. Gut Microbes, 2017, 8(3): 225-237. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2017.1286006

|

| [31] |

Truong DT, Tett A, Pasolli E, et al. Microbial strain-level population structure and genetic diversity from metagenomes. Genome Res, 2017, 27(4): 626-638. DOI:10.1101/gr.216242.116

|

| [32] |

Jin H, You LJ, Zhao FY, et al. Hybrid, ultra-deep metagenomic sequencing enables genomic and functional characterization of low-abundance species in the human gut microbiome. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14(1): 2021790. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2021.2021790

|

| [33] |

Salter SJ, Cox MJ, Turek EM, et al. Reagent and laboratory contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses. BMC Biol, 2014, 12(1): 1-12. DOI:10.1186/1741-7007-12-1

|

| [34] |

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol, 2011, 12(6): R60. DOI:10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60

|

| [35] |

Lynch MDJ, Neufeld JD. Ecology and exploration of the rare biosphere. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2015, 13(4): 217-229. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro3400

|

| [36] |

Cangelosi GA, Meschke JS. Dead or alive: molecular assessment of microbial viability. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014, 80(19): 5884-5891. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01763-14

|

| [37] |

Bollmann A, Lewis K, Epstein SS. Incubation of environmental samples in a diffusion chamber increases the diversity of recovered isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2007, 73(20): 6386-6390. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01309-07

|

| [38] |

Stone J, Teixobactin JS. iChip promise hope against antibiotic resistance. 2015.

|

| [39] |

Lagier JC, Khelaifia S, Alou MT, et al. Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nat Microbiol, 2016, 1: 16203. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203

|

| [40] |

Villa MM, Bloom RJ, Silverman JD, et al. Interindividual variation in dietary carbohydrate metabolism by gut bacteria revealed with droplet microfluidic culture. mSystems, 2020, 5(3): e00864-19.

|

| [41] |

Sizova MV, Hohmann T, Hazen A, et al. New approaches for isolation of previously uncultivated oral bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2012, 78(1): 194-203. DOI:10.1128/AEM.06813-11

|

| [42] |

Seng P, Abat C, Rolain JM, et al. Identification of rare pathogenic bacteria in a clinical microbiology laboratory: impact of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol, 2013, 51(7): 2182-2194. DOI:10.1128/JCM.00492-13

|

| [43] |

Kaeberlein T, Lewis K, Epstein SS. Isolating "uncultivable" microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment. Science, 2002, 296(5570): 1127-1129. DOI:10.1126/science.1070633

|

| [44] |

Nichols D, Cahoon N, Trakhtenberg EM, et al. Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of uncultivable microbial species. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2010, 76(8): 2445-2450. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01754-09

|

| [45] |

Stewart EJ. Growing unculturable bacteria. J Bacteriol, 2012, 194(16): 4151-4160. DOI:10.1128/JB.00345-12

|

| [46] |

Rajilić-Stojanović M, Smidt H, De Vos WM. Diversity of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Environ Microbiol, 2007, 9(9): 2125-2136. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01369.x

|

| [47] |

Zou Y, Xue W, Luo G, et al. 1, 520 reference genomes from cultivated human gut bacteria enable functional microbiome analyses. Nat Biotechnol, 2019, 37(2): 179-185. DOI:10.1038/s41587-018-0008-8

|

| [48] |

Liu C, Zhou N, Du MX, et al. The mouse gut microbial biobank expands the coverage of cultured bacteria. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 79. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13836-5

|

| [49] |

Cross KL, Campbell JH, Balachandran M, et al. Targeted isolation and cultivation of uncultivated bacteria by reverse genomics. Nat Biotechnol, 2019, 37(11): 1314-1321. DOI:10.1038/s41587-019-0260-6

|

| [50] |

Liu C, Du MX, Abuduaini R, et al. Enlightening the taxonomy darkness of human gut microbiomes with cultured biobank. Microbiome, 2021, 9(1): 1-29. DOI:10.1186/s40168-020-00939-1

|

| [51] |

DeFilipp Z, Bloom PP, Torres Soto M, et al. Drug-resistant E. coli bacteremia transmitted by fecal microbiota transplant. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(21): 2043-2050. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1910437

|

| [52] |

Marcella C, Cui BT, Kelly CR, et al. Systematic review: the global incidence of faecal microbiota transplantation-related adverse events from 2000 to 2020. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 53(1): 33-42.

|

| [53] |

Merrick B, Allen L, Zain NMM, et al. Regulation, risk and safety of faecal microbiota transplant. Infect Prev Pract, 2020, 2(3): 100069. DOI:10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100069

|

| [54] |

Vyas D, Aekka A, Vyas A. Fecal transplant policy and legislation. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(1): 6-11. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.6

|

| [55] |

Chang CJ, Lin TL, Tsai YL, et al. Next generation probiotics in disease amelioration. J Food Drug Anal, 2019, 27(3): 615-622. DOI:10.1016/j.jfda.2018.12.011

|

| [56] |

Tsai YL, Lin TL, Chang CJ, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases. J Biomed Sci, 2019, 26(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1186/s12929-018-0495-4

|

| [57] |

De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Zitoun C, et al. Microbiota-produced succinate improves glucose homeostasis via intestinal gluconeogenesis. Cell Metab, 2016, 24(1): 151-157. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.013

|

| [58] |

Hjorth MF, Blædel T, Bendtsen LQ, et al. Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio predicts body weight and fat loss success on 24-week diets varying in macronutrient composition and dietary fiber: results from a post-hoc analysis. Int J Obesity, 2019, 43(1): 149-157. DOI:10.1038/s41366-018-0093-2

|

| [59] |

Pedersen HK, Gudmundsdottir V, Nielsen HB, et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature, 2016, 535(7612): 376-381. DOI:10.1038/nature18646

|

| [60] |

McFarland LV, Evans CT, Goldstein EJC. Strain-specificity and disease-specificity of probiotic efficacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne), 2018, 5: 124.

|

| [61] |

De Filippis F, Esposito A, Ercolini D. Outlook on next-generation probiotics from the human gut. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2022, 79(2): 1-18.

|

| [62] |

Cani PD, Depommier C, Derrien M, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 1-13.

|

| [63] |

Nikitina AS, Kharlampieva DD, Babenko VV, et al. Complete genome sequence of an enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis clinical isolate. Genome Announc, 2015, 3(3): e00450-15.

|

| [64] |

Deng HM, Yang SQ, Zhang YC, et al. Bacteroides fragilis prevents Clostridium difficile infection in a mouse model by restoring gut barrier and microbiome regulation. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 2976. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02976

|

| [65] |

Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka K, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Hupp T, et al. Next-generation probiotics-do they open new therapeutic strategies for cancer patients?. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14(1): 2035659. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2022.2035659

|

| [66] |

Maioli TU, Borras-Nogues E, Torres L, et al. Possible benefits of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii for obesity-associated gut disorders. Front Pharmacol, 2021, 12: 740636. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2021.740636

|

| [67] |

Ferreira-Halder CV, Faria AVDS, Andrade SS. Action and function of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2017, 31(6): 643-648. DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.011

|

| [68] |

Hansen AK, Hansen CHF, Krych L, et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on rodent models of human disease. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(47): 17727-17736. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17727

|

| [69] |

Mazier W, Le Corf K, Martinez C, et al. A new strain of Christensenella minuta as a potential biotherapy for obesity and associated metabolic diseases. Cells, 2021, 10(4): 823. DOI:10.3390/cells10040823

|

| [70] |

Le HH, Lee MT, Besler KR, et al. Host hepatic metabolism is modulated by gut microbiota-derived sphingolipids. Cell Host Microbe, 2022, 30(6): 798-808.e7. DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2022.05.002

|

| [71] |

Sangineto M, Grander C, Grabherr F, et al. Recovery of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ameliorates hepatic steatosis in experimental alcohol-related liver disease. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14(1): 2089006. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2022.2089006

|

| [72] |

Wrzosek L, Miquel S, Noordine ML, et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii influence the production of mucus glycans and the development of goblet cells in the colonic epithelium of a gnotobiotic model rodent. BMC Biol, 2013, 11(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1186/1741-7007-11-1

|

| [73] |

Le Roy T, Moens De Hase E, Van Hul M, et al. Dysosmobacter welbionis is a newly isolated human commensal bacterium preventing diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders in mice. Gut, 2022, 71(3): 534-543. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323778

|

| [74] |

Dechelotte PM, Breton J, Trotin-Picolo C, et al. The probiotic strain h. Alvei ha4597® improves weight loss in overweight subjects under moderate hypocaloric diet: a multicenter randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Nutr ESPEN, 2020, 40: 658-659.

|

| [75] |

Lucas N, Legrand R, Deroissart C, et al. Hafnia alvei HA4597 strain reduces food intake and body weight gain and improves body composition, glucose, and lipid metabolism in a mouse model of hyperphagic obesity. Microorganisms, 2019, 8(1): 35. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms8010035

|

| [76] |

Qiao SS, Bao L, Wang K, et al. Activation of a specific gut Bacteroides-folate-liver axis benefits for the alleviation of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Cell Rep, 2020, 32(6): 108005. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108005

|

| [77] |

Wang K, Liao MF, Zhou N, et al. Parabacteroides distasonis alleviates obesity and metabolic dysfunctions via production of succinate and secondary bile acids. Cell Rep, 2019, 26(1): 222-235.e5. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.028

|