生物基塑料单体5-氨基戊酸的生物合成新途径

康雅琦

,

罗若诗

,

林凡祯

,

程杰

,

周桢

,

王丹

生物工程学报  2023, Vol. 39 2023, Vol. 39 Issue (5): 2070-2080 Issue (5): 2070-2080 |

由于全球水资源的污染、气候变迁及石油供应不足等问题,人类社会的可持续发展受到严峻挑战,用生物基化学品代替传统石化衍生化学品受到了学术界和企业界的重点关注。近年来,研究者们已经利用微生物生产了许多重要的化学品,例如6-氨基己酸[1]、果糖[2]、扁桃酸[3]、维生素B12[4]、柚皮素[5]、4-羟基苯甲酸[6]、姜黄素[7]、羟基酪醇[8]等。生物基塑料单体是一种新型的化工原料,它带有适当官能团,能够聚合生成结构和性能可控的高分子材料。目前,运用生物技术合成了许多生物基材料单体,如己二酸[9]、戊二酸[10]、1, 3-二氨基丙烷[11]、二氨基戊烷[12-13]、1, 3-丙二醇[14]和1, 2-丙二醇[15]。值得一提的是,5-氨基戊酸(5-aminovalanoic acid, 5AVA)是合成聚酰亚胺的有前途的平台化合物,其聚合成的聚酰胺材料如尼龙5[16]和尼龙56[17]具有耐高温和耐有机溶剂的特性,可作为一次性用品、衣服、汽车、飞机和建筑材料等的原材料。

5AVA可用于戊二酸[18-19]、δ-戊内酰胺[20]、1, 5-戊二醇[21]和5-羟基戊酸[22]等C5平台化学品的生产。目前,5AVA可由二氧化铈负载的纳米金催化哌啶氧化物进行合成[23]。然而,这种化学合成方法不仅需要很高的温度,产率较低,且污染较大[23],因此寻找生产5AVA的替代方法是十分必要的。随着生物技术的快速发展,通过代谢工程和合成生物学合成5AVA引起了研究者广泛的关注[19]。

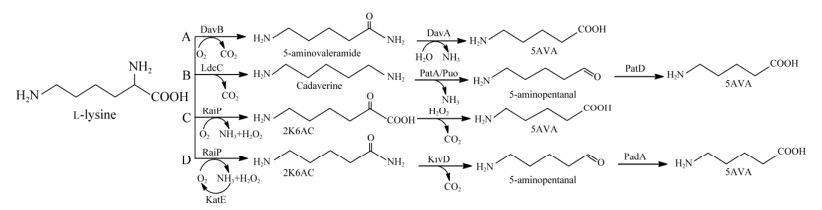

5AVA的合成与恶臭假单胞菌(Pseudomonas fulticans)中的L-赖氨酸分解代谢密切相关[24]。通过L-lys2-单加氧酶(DavB)和5-氨基戊酸酰胺水解酶(DavA)的过表达,产生了5AVA (图 1A)[25]。Park等[26]利用大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli) WL3110/DavA-DavB生产了3.6 g/L的5AVA,滴度相对较低。因此,他们进一步在谷氨酸棒杆菌(Corynebacterium glutamicum)中采用人工H36启动子,产生了33.1 g/L的5AVA[27]。值得一提的是,Li等[28]采用L-赖氨酸特异性渗透酶(L-lysine permease, LysP)将5AVA滴度提高至63.2 g/L (表 1),Wang等[29]采用全细胞催化法,利用DavB和DavA将5AVA滴度提高至240.70 g/L (表 1)。此外,Jorge等[30]以1, 5-戊二胺和5-氨基戊醛为中间体,利用L-赖氨酸产生5AVA (图 1B)。研究发现,通过日本鲭(Scomber japonicas) L-赖氨酸α-氧化酶(RaiP)的表达,可以L-赖氨酸盐酸盐(L-lys HCl)为底物,以2-酮基-6-氨基己酸(2-keto-6-aminohexanoic acid, 2K6AC)为中间体,生产5AVA,产量可达到29.12 g/L[31] (图 1C)。但是由于此途径添加了乙醇和H2O2,是不安全和不经济的[31]。除此之外,研究发现通过固定在载体上的RaiP可以获得13.4 g/L 5AVA[32]。进一步地,大孔吸附树脂AK-1的使用可以实现从生物转化液中分离出5AVA[33],纯度可达99.3%。

|

| 图 1 L-赖氨酸合成5AVA的微生物途径 Fig. 1 Microbial pathway for the synthesis of 5AVA from L-lysine. |

| |

| Synthetic pathway | Host strain | Strategy | Description | 5AVA titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Substrate/Feedstock | References |

| A | E. coli | Whole-cell biotransformation | Expression of DavB and DavA in E. coli | 240.70 | 0.70 | L-lysine | [29] |

| A | E. coli | Enzymatic catalysis | Overexpression of DavB, DavA, PP2911 from P. putida and LysP from E. coli |

63.20 | 0.62 | L-lysine | [28] |

| A | C. glutamicum | Fed-batch fermentation | Expression of codon-optimized davA and davB, promoter engineering |

33.10 | 0.10 | Glucose | [27] |

| A | C. glutamicum | Fed-batch fermentation | Pretreatment, hydrolysis, purification and concentration of the Miscanthus hydrolyzate solution |

12.51 | 0.10 | Miscanthus hydrolyzate | [26] |

| B | C. glutamicum | Fermentation | N-acetylcadaverine and glutarate in a genome-streamlined L-lysine producing strain expressing ldcC, patA, and patD from E. coli |

5.10 | 0.13 | Glucose and alternative carbon sources |

[30] |

| B | C. glutamicum | Fermentation | C. glutamicum GSLA21gabTDP with overexpression of LdcC, Puo, and PatD |

3.70 | 0.09 | Glucose | [46] |

| C | E. coli | Whole-cell biotransformation | Overexpression of RaiP from S. japonicus and addition of 4% ethanol and 10 mmol/L H2O2 |

29.12 | 0.44 | L-lysine HCl | [31] |

| C | E. coli | Whole-cell biotransformation | Overexpression of RaiP from S. japonicus and whole-cell catalysts with ethanol pretreatment |

50.62 | 0.51 | L-lysine HCl | [43] |

| D | E. coli | Whole-cell biotransformation | Combination of native RaiP, KivD, PadA, KatE, and LysP, without addition of ethanol and H2O2 |

57.52 | 0.40 | L-lysine HCl | This study |

在天然途径中,α-酮酸脱羧酶(KivD)可催化多种α-酮酸生成醛[34-36],在α-酮酸的脱羧中展现出高效活性[37-38]。与野生型KivD的底物相比,KivD突变体催化的底物链长相对较长,如2-丙酮-4-甲基己酸和2-酮-3-甲基戊酸[39],而天然途径中的KivD催化的底物链长较短,如2-酮异戊酸和α-酮己二酸[36, 39]。在大肠杆菌中,以2-酮丁酸盐为底物表达来自乳酸乳球菌(Lactococcus lactis)中的醇脱氢酶2 (alcohol dehydrogenase 2, ADH2)和KivD,可以生产2 g/L 1-丙醇[40]。L-赖氨酸α-氧化酶(RaiP)将L-赖氨酸的α-氨基氧化成羰基,同时产生NH3和H2O2,生成中间体2K6AC。乙醛脱氢酶(PadA)可催化醛基转变为羧基。

与野生型相比,F381和M461中的2个KivD突变体表现出更高的底物识别和催化效率。此外,KatE和LysP的过表达有助于H2O2的去除和L-赖氨酸的转运,从而增加5AVA的产量。在本研究中,将来自S. japonicus的L-赖氨酸α-氧化酶、乳球菌的α-酮酸脱羧酶和大肠杆菌的醛脱氢酶,在大肠杆菌BL21(DE3)中过表达,以2-酮基-6-氨基己酸酯为中间体,构建了生物合成5AVA的新途径(图 1D)。这种新途径在工业应用中具有广阔的前景,它不仅提高了L-赖氨酸的价值,而且实现了5AVA在大肠杆菌中高效地合成,将为尼龙5和尼龙56发展成为一种新型的生物基塑料奠定基础。

1 材料与方法 1.1 菌株和质粒本研究涉及的菌株和质粒如表 2所示。将质粒pCJ01、pETaRPK、pETaRPK#、pEAkatE或pEAKL转入敲除了cadA的大肠杆菌BL21(DE3),分别获得菌株CJ02、CJ06、CJ07、CJ08或CJ09。

| Strains and plasmids | Description | Sources |

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | Wild type | Novagen |

| BL21(DE3) | Wild type | Novagen |

| ML03 | E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔcadA | [41] |

| CJ00 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pET21a | [31] |

| CJ01 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pCJ01 | [31] |

| CJ02 | E. coli ML03 harboring plasmid pCJ01 | [31] |

| CJ05 | E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring plasmid pETaRPK | This study |

| CJ06 | E. coli ML03 harboring plasmid pETaRPK | This study |

| CJ07 | E. coli ML03 harboring plasmid pETaRPK# | This study |

| CJ08 | E. coli ML03 harboring plasmid pETaRPK# and pZAkatE | This study |

| CJ09 | E. coli ML03 harboring plasmid pETaRPK# and pZAKL | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pZA22 | Empty plasmid used as control, KanR | [1] |

| pCJ01 | pET21a-raiP, pET21a carries a L-lysine α-oxidase gene (raiP) from S. japonicus with Nde I and BamH I restrictions, AmpR |

[31] |

| pETaRPK | pET21a-raiP-kivD-padA, pET21a carries a L-lysine α-oxidase gene (raiP) from S. japonicus, a α-ketoacid decarboxylase gene (kivD) from L. lactis and a aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (padA) from E. coli, AmpR |

This study |

| pETaRPK# | pET21a-raiP-kivD#-padA, pET21a carries a L-lysine α-oxidase gene (raiP) from S. japonicus, a α-ketoacid decarboxylase mutant (F381A/V461A) gene from L. lactis and an aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (padA) from E. coli, AmpR |

This study |

| pZAkatE | pZA22-katE, pZA22 carries a catalase gene (katE) from E. coli, KanR | This study |

| pZAKL | pZA22-katE-lysP, pZA22 carries a catalase gene (katE) from E. coli and a lysine permease gene (lysP) from E. coli, KanR |

This study |

将携带相应质粒的大肠杆菌在100 mg/L氨苄青霉素的LB琼脂平板上培养,并在37 ℃下生长12 h。单个菌落接种到补充有100 mg/L氨苄青霉素的2 mL LB肉汤中,在37 ℃、250 r/min条件下培养12 h。

培养基为基本培养基:5 g/L酵母提取物,10 g/L胰蛋白酶,15 g/L葡萄糖,0.1 g/L FeCl3,2.1 g/L柠檬酸,2.5 g/L (NH4)2SO4,0.5 g/LK3PO4·3H2O,1.0 mmol/L MgSO4,3 g/L KH2PO4,0.5 mmol/L硫胺素二磷酸(thiamine diphosphate, ThDP),抗生素。OD600达到0.5后,添加0.5 mmol/L异丙基-β-d-硫代半乳糖苷(isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside, IPTG)和6.5 g/L L-赖氨酸盐酸,并继续培养。

工程菌株的补料分批生物转化在5.0 L发酵罐中进行。发酵培养基组成为:55 g/L葡萄糖、1.6 g/L MgSO4·7H2O、0.007 56 g/L FeSO4·7H2O、1.6 g/L (NH4)2SO4、2 g/L柠檬酸、7.5 g/L K2HPO4·3H2O、0.02 g/L Na2SO4、0.006 4 g/L ZnSO4、0.000 6 g/L Cu2SO4·5H2O、0.004 g/L CoCl2·6H2O[41]。通过添加氨水将pH控制在6.7–6.9,将温度设定为30 ℃。发酵期间逐渐添加消泡剂289,防止在生物转化过程中形成泡沫。在整个发酵过程中,葡萄糖和L-赖氨酸的浓度分别保持在15 g/L和20 g/L左右。

1.3 蛋白质的表达和纯化37 ℃时,向用于蛋白质表达的培养基的LB琼脂中补充0.5 mmol/L ThDP。OD600达到0.5后,加入0.5 mmol/L IPTG。20 ℃时,用磷酸钾缓冲液(KPB, 50 mmol/L, pH 8.0)洗涤细胞。在50 mmol/L KPB的冰浴中利用超声处理破坏细胞,并使用Ni-NTA柱用AKTA纯化器10纯化酶[1]。使用SpectraMax M2e在280 nm处测量蛋白质的浓度[31]。

1.4 酶测定RaiP的氧化活性是通过测量H2O2的生成速率来确定的[31]。利用耦合酶测定法,在30 ℃下测定KivD和KivD突变(KivD*)的脱羧活性[36]。反应混合物包含1.0 mmol/L NAD+、1.1 μmol/L PadA、1.1 μmol/L RaiP、0.85 μmol/L KivD或KivD*以及不同浓度的L-赖氨酸缓冲液(50 mmol/L KPB, pH 8.0, 1 mmol/L MgSO4, 1.0 mmol/L TCEP, 0.5 mmol/L ThDP)。在刚开始反应时添加底物L-赖氨酸,并在340 nm处监测NADH的形成,消光系数为6.22 mmol/(L·cm)。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 大肠杆菌合成5AVA的人工合成路线的构建5AVA的生物合成途径包括3个步骤:(1) 通过RaiP将L-赖氨酸脱氨转化为中间体2K6AC;(2) 通过KivD使2K6AC脱羧产生5-氨基戊醛;(3) 通过PadA将5-氨基戊醛氧化为5AVA (图 1D)。首先,构建质粒pETaRPK,并将其导入大肠杆菌BL21(DE3)中以获得菌株CJ05,在T7启动子下共表达RaiP、KivD和PadA。为了减少L-赖氨酸降解为5-戊二胺,敲除赖氨酸脱羧酶基因cadA以获得菌株CJ06。值得注意的是,菌株CJ01、CJ02、CJ05和CJ06也可以生产5AVA。菌株CJ00从6.5 g/L L-lys HCl生产了0.06 g/L 5AVA,消耗量为0.01 g/g L-lys (表 3)。对于工程菌株CJ01,可生0.23 g/L 5AVA。此外,菌株CJ05通过图 1D所示的途径生产1.66 g/L的5AVA,与单基因途径(图 1C)相比,产量增加了774%。

| Strains | Plasmids | L-lysine HCl (g/L) |

5AVA titer (g/L) |

| CJ00 | BL21(DE3)/pET21a | 6.5 | 0.06 |

| CJ01 | BL21(DE3)/pET21a-raiP | 6.5 | 0.23 |

| CJ02 | ML03/pET21a-raiP | 6.5 | 0.32 |

| CJ05 | BL21(DE3)/pET21aRPK | 6.5 | 1.66 |

| CJ06 | ML03/pET21aRPK | 6.5 | 1.95 |

由此可见,利用RaiP、KivD、PadA这3种关键酶,2K6AC作为中间产物生产5AVA途径具有可行性。

2.2 过氧化氢酶KcatE和赖氨酸渗透酶LysP的过表达有利于5AVA产量的增加本研究采用了4种策略来提高5AVA的产量。首先,敲除赖氨酸脱羧酶基因cadA。其次,选择L-lys HCl作为底物,以提高L-lys的利用率[31, 41, 42]。然后,H2O2可以抑制细胞生长[43],从而影响目标产物的产生。Liu等[44]发现过氧化氢酶的表达使H2O2的含量显著降低,α-酮戊二酸的产量显著增加。在本研究中,菌株CJ08中katE、raiP、kivD#和padA的共表达下产生1.88 g/L的5AVA,与菌株CJ07相比没有显著差异(表 4)。事实上,KatE的过表达会消除RaiP产生的H2O2。如表 4所示,在发酵期间,KatE的引入并没有显著增加OD600和5AVA的产量。相反,它降低了OD600,可能是由于过多的基因表达增加了细胞负担,导致细胞量减少[45]。然而,在发酵罐中,H2O2可以显著抑制细胞生长,导致5AVA的产量有限[31, 42]。因此进一步地,本研究将过表达赖氨酸转运蛋白基因lysP插入质粒pZAkatE中以形成新的质粒pZAKL。如表 4所示,菌株CJ09可产生1.93 g/L的5AVA。

| Strains | Time (h) |

Cell density (OD600) |

Glucose consumed (g/L) |

5AVA production (g/L) |

5AVA yield (g/g)a |

| CJ06 | 12 | 5.24±0.38 | 7.22±0.33 | 0.85±0.04 | 0.19±0.03 |

| 24 | 8.15±0.52 | 11.36±0.46 | 1.69±0.03 | 0.35±0.03 | |

| CJ07 | 12 | 5.19±0.41 | 7.09±0.25 | 0.96±0.02 | 0.25±0.01 |

| 24 | 8.08±0.55 | 11.25±0.48 | 1.85±0.02 | 0.39±0.03 | |

| CJ08 | 12 | 5.14±0.36 | 7.02±0.28 | 0.94±0.01 | 0.25±0.02 |

| 24 | 7.91±0.46 | 11.17±0.41 | 1.88±0.02 | 0.40±0.03 | |

| CJ09 | 12 | 5.08±0.33 | 6.88±0.18 | 1.01±0.03 | 0.23±0.01 |

| 24 | 7.85±0.42 | 11.11±0.39 | 1.93±0.01 | 0.41±0.02 | |

| Data are presented as |

|||||

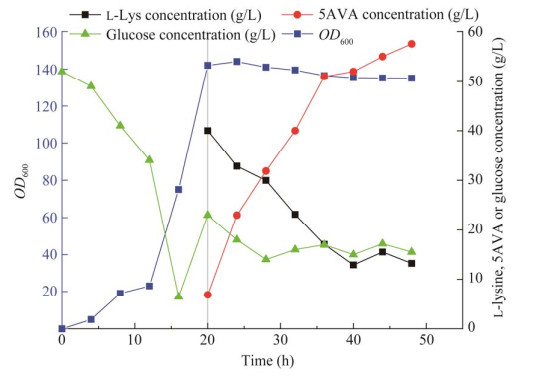

工程菌株CJ09的补料分批生物转化结果如图 2所示。CJ09生长速度很快,在18 h内的最高细胞浓度(OD600)可达到142。添加L-lys HCl后的18–36 h之间,5AVA累积至48.3 g/L。随着发酵时间增加至48 h,5AVA累积至57.52 g/L,5AVA的产率和产量分别为1.09 g/(L·h)和0.65 g/g L-赖氨酸。而菌株CJ02生产了9.16 g/L 5AVA,产率为0.11 g/g L-lys。菌株CJ08中KatE的表达不会影响5AVA的产量,而且其5AVA的产量却比CJ07明显增加达到45.92 g/L,CJ07的滴度仅为16.48 g/L (表 4)。这是因为H2O2对CJ07的生长有明显的抑制作用,使其OD600只有40。上述结果表明,本文中的合成路线可以高效地生产5AVA。

|

| 图 2 工程菌株CJ09在5 L发酵罐中合成5AVA Fig. 2 Synthesis of 5AVA by engineered strain CJ09 in 5 L fermentor. |

| |

在反应机理方面,本文提出的5AVA合成策略主要包括3个步骤:(1) RaiP催化生产中间体6A2KCA;(2) KivD将2K6AC脱羧为5-氨基戊醛;(3) PadA将5-氨基戊醛氧化生成5AVA。与先前的全细胞转化(表 1)相比,5AVA的滴度从29.12 g/L增加至57.52 g/L,增加了约97.5%;结果证明,H2O2会抑制细胞生长和酶活性,导致5AVA的产率较低[31]。本文中的途径与其他发酵生产5AVA的合成途径[30] (表 1)相比,5AVA的滴度从5.1 g/L提高至57.52 g/L。与另一种全细胞催化工作[42]相比,5AVA的滴度从50.62 g/L提高至57.52 g/L,提高了约13.60%。而且在不添加乙醇和H2O2的条件下,5AVA的工业化生产具有更高的安全性和经济性。

3 结论本研究提出并优化了大肠杆菌生产5AVA的生物合成途径。通过引入过氧化氢酶KatE降解H2O2,减少H2O2对酶活性和细胞生长的抑制,从而使5AVA有较高的产率。本实验采用可再生基质和简单的培养条件,具有较高的产率,对环境污染小。提高底物利用率和H2O2分解效率均有助于提高5AVA的产量,这有可能成为其他化学品可持续生物合成的普适性策略。

| [1] |

CHENG J, HU G, XU YQ, TORRENS-SPENCE MP, ZHOU XH, WANG D, WENG JK, WANG QH. Production of nonnatural straight-chain amino acid 6-aminocaproate via an artificial iterative carbon-chain-extension cycle. Metabolic Engineering, 2019, 55: 23-32. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.06.009

|

| [2] |

YANG JG, ZHU YM, MEN Y, SUN SS, ZENG Y, ZHANG Y, SUN YX, MA YH. Pathway construction in Corynebacterium glutamicum and strain engineering to produce rare sugars from glycerol. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64(50): 9497-9505. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03423

|

| [3] |

YOUN JW, ALBERMANN C, SPRENGER GA. In vivo cascade catalysis of aromatic amino acids to the respective mandelic acids using recombinant E. coli cells expressing hydroxymandelate synthase (HMS) from Amycolatopsis mediterranei. Molecular Catalysis, 2020, 483: 110713. DOI:10.1016/j.mcat.2019.110713

|

| [4] |

FANG H, LI D, KANG J, JIANG PT, SUN JB, ZHANG DW. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for de novo biosynthesis of vitamin B12. Nature Communications, 2018, 9: 4917. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-07412-6

|

| [5] |

GAO S, ZHOU HR, ZHOU JW, CHEN J. Promoter-library-based pathway optimization for efficient (2S)-naringenin production from p-coumaric acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(25): 6884-6891. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01130

|

| [6] |

KLENK JM, ERTL J, RAPP L, FISCHER MP, HAUER B. Expression and characterization of the benzoic acid hydroxylase CYP199A25 from Arthrobacter sp.. Molecular Catalysis, 2020, 484: 110739. DOI:10.1016/j.mcat.2019.110739

|

| [7] |

RODRIGUES JL, GOMES D, RODRIGUES LR. A combinatorial approach to optimize the production of curcuminoids from tyrosine in Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2020, 8: 59. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00059

|

| [8] |

ZENG BY, LAI YM, LIU LJ, CHENG J, ZHANG Y, YUAN JF. Engineering Escherichia coli for high-yielding hydroxytyrosol synthesis from biobased L-tyrosine. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(29): 7691-7696. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03065

|

| [9] |

ZHAO M, HUANG DX, ZHANG XJ, KOFFAS MAG, ZHOU JW, DENG Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for producing adipic acid through the reverse adipate-degradation pathway. Metabolic Engineering, 2018, 47: 254-262. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.002

|

| [10] |

ZHAO M, LI GH, DENG Y. Engineering Escherichia coli for glutarate production as the C5 platform backbone. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 84(16): e814-e818.

|

| [11] |

CHAE TU, KIM WJ, CHOI S, PARK SJ, LEE SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 1, 3-diaminopropane, a three carbon diamine. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 13040. DOI:10.1038/srep13040

|

| [12] |

KIND S, JEONG WK, SCHRÖDER H, WITTMANN C. Systems-wide metabolic pathway engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum for bio-based production of diaminopentane. Metabolic Engineering, 2010, 12(4): 341-351. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2010.03.005

|

| [13] |

RUI JQ, YOU SP, ZHENG YX, WANG CY, GAO YT, ZHANG W, QI W, SU RX, HE ZM. High-efficiency and low-cost production of cadaverine from a permeabilized-cell bioconversion by a lysine-induced engineered Escherichia coli. Bioresource Technology, 2020, 302: 122844. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122844

|

| [14] |

NAKAMURA CE, WHITED GM. Metabolic engineering for the microbial production of 1, 3-propanediol. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2003, 14(5): 454-459. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.005

|

| [15] |

NIIMI S, SUZUKI N, INUI M, YUKAWA H. Metabolic engineering of 1, 2-propanediol pathways in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2011, 90(5): 1721-1729. DOI:10.1007/s00253-011-3190-x

|

| [16] |

ADKINS J, JORDAN J, NIELSEN DR. Engineering Escherichia coli for renewable production of the 5-carbon polyamide building-blocks 5-aminovalerate and glutarate. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2013, 110(6): 1726-1734. DOI:10.1002/bit.24828

|

| [17] |

PARK SJ, KIM EY, NOH W, OH YH, KIM HY, SONG BK, CHO KM, HONG SH, LEE SH, JEGAL J. Synthesis of nylon 4 from gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) produced by recombinant Escherichia coli. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2013, 36(7): 885-892. DOI:10.1007/s00449-012-0821-2

|

| [18] |

ROHLES CM, GIEßELMANN G, KOHLSTEDT M, WITTMANN C, BECKER J. Systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of the carbon-5 platform chemicals 5-aminovalerate and glutarate. Microbial Cell Factories, 2016, 15(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1186/s12934-015-0402-6

|

| [19] |

HONG YG, MOON YM, HONG JW, NO SY, CHOI TR, JUNG HR, YANG SY, BHATIA SK, AHN JO, PARK KM, YANG YH. Production of glutaric acid from 5-aminovaleric acid using Escherichia coli whole cell bio-catalyst overexpressing GabTD from Bacillus subtilis. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2018, 118: 57-65. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2018.07.002

|

| [20] |

ZHANG JW, BARAJAS JF, BURDU M, WANG G, BAIDOO EE, KEASLING JD. Application of an acyl-CoA ligase from Streptomyces aizunensis for lactam biosynthesis. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2017, 6(5): 884-890. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00372

|

| [21] |

PARK SJ, OH YH, NOH W, KIM HY, SHIN JH, LEE EG, LEE S, DAVID Y, BAYLON MG, SONG BK, JEGAL J, LEE SY, LEE SH. High-level conversion of L-lysine into 5-aminovalerate that can be used for nylon 6, 5 synthesis. Biotechnology Journal, 2014, 9(10): 1322-1328. DOI:10.1002/biot.201400156

|

| [22] |

LIU P, ZHANG HW, LV M, HU MD, LI Z, GAO C, XU P, MA CQ. Enzymatic production of 5-aminovalerate from L-lysine using L-lysine monooxygenase and 5-aminovaleramide amidohydrolase. Scientific Reports, 2014, 4: 5657. DOI:10.1038/srep05657

|

| [23] |

DAIRO TO, NELSON NC, SLOWING Ⅱ, ANGELICI RJ, WOO LK. Aerobic oxidation of cyclic amines to lactams catalyzed by ceria-supported nanogold. Catalysis Letters, 2016, 146(11): 2278-2291. DOI:10.1007/s10562-016-1834-2

|

| [24] |

YING HX, TAO S, WANG J, MA WC, CHEN KQ, WANG X, OUYANG PK. Expanding metabolic pathway for de novo biosynthesis of the chiral pharmaceutical intermediate l-pipecolic acid in Escherichia coli. Microbial Cell Factories, 2017, 16(1): 1-11. DOI:10.1186/s12934-016-0616-2

|

| [25] |

JOO JC, OH YH, YU JH, HYUN SM, KHANG TU, KANG KH, SONG BK, PARK K, OH MK, LEE SY, PARK SJ. Production of 5-aminovaleric acid in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum strains from a Miscanthus hydrolysate solution prepared by a newly developed Miscanthus hydrolysis process. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 245: 1692-1700. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.131

|

| [26] |

PARK SJ, KIM EY, NOH W, PARK HM, OH YH, LEE SH, SONG BK, JEGAL J, LEE SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of 5-aminovalerate and glutarate as C5 platform chemicals. Metabolic Engineering, 2013, 16: 42-47. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.011

|

| [27] |

SHIN JH, PARK SH, OH YH, CHOI JW, LEE MH, CHO JS, JEONG KJ, JOO JC, YU J, PARK SJ, LEE SY. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for enhanced production of 5-aminovaleric acid. Microbial Cell Factories, 2016, 15(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1186/s12934-015-0402-6

|

| [28] |

LI Z, XU J, JIANG TT, GE YS, LIU P, ZHANG MM, SU ZG, GAO C, MA CQ, XU P. Overexpression of transport proteins improves the production of 5-aminovalerate from L-lysine in Escherichia coli. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 30884. DOI:10.1038/srep30884

|

| [29] |

WANG X, CAI PP, CHEN KQ, OUYANG PK. Efficient production of 5-aminovalerate from L-lysine by engineered Escherichia coli whole-cell biocatalysts. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2016, 134: 115-121. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2016.10.008

|

| [30] |

JORGE JMP, PÉREZ-GARCÍA F, WENDISCH VF. A new metabolic route for the fermentative production of 5-aminovalerate from glucose and alternative carbon sources. Bioresource Technology, 2017, 245: 1701-1709. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.108

|

| [31] |

CHENG J, ZHANG YN, HUANG MH, CHEN P, ZHOU XH, WANG D, WANG QH. Enhanced 5-aminovalerate production in Escherichia coli from L-lysine with ethanol and hydrogen peroxide addition. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2018, 93(12): 3492-3501.

|

| [32] |

PUKIN AV, BOERIU CG, SCOTT EL, SANDERS JPM, FRANSSEN MCR. An efficient enzymatic synthesis of 5-aminovaleric acid. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2010, 65(1/2/3/4): 58-62.

|

| [33] |

XU S, LU XD, LI M, WANG J, LI H, HE X, FENG J, WU JL, CHEN KQ, OUYANG PK. Separation of 5-aminovalerate from its bioconversion liquid by macroporous adsorption resin: mechanism and dynamic separation. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2020, 95(3): 686-693.

|

| [34] |

XIONG MY, DENG J, WOODRUFF AP, ZHU MS, ZHOU J, PARK SW, LI H, FU Y, ZHANG KC. A bio-catalytic approach to aliphatic ketones. Scientific Reports, 2012, 2: 311. DOI:10.1038/srep00311

|

| [35] |

JAMBUNATHAN P, ZHANG KC. Novel pathways and products from 2-keto acids. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2014, 29: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.01.008

|

| [36] |

WANG J, WU YF, SUN XX, YUAN QP, YAN YJ. De novo biosynthesis of glutarate via α-keto acid carbon chain extension and decarboxylation pathway in Escherichia coli. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2017, 6(10): 1922-1930. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00136

|

| [37] |

ATSUMI S, HANAI T, LIAO JC. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature, 2008, 451(7174): 86-89. DOI:10.1038/nature06450

|

| [38] |

CHEN GS, SIAO SW, SHEN CR. Saturated mutagenesis of ketoisovalerate decarboxylase V461 enabled specific synthesis of 1-pentanol via the ketoacid elongation cycle. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 11284. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11624-z

|

| [39] |

ZHANG KC, SAWAYA MR, EISENBERG DS, LIAO JC. Expanding metabolism for biosynthesis of nonnatural alcohols. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(52): 20653-20658. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0807157106

|

| [40] |

SHEN CR, LIAO JC. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for 1-butanol and 1-propanol production via the keto-acid pathways. Metabolic Engineering, 2008, 10(6): 312-320. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2008.08.001

|

| [41] |

CHENG J, HUANG YD, MI L, CHEN WJ, WANG D, WANG QH. An economically and environmentally acceptable synthesis of chiral drug intermediate l-pipecolic acid from biomass-derived lysine via artificially engineered microbes. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2018, 45(6): 405-415. DOI:10.1007/s10295-018-2044-2

|

| [42] |

CHENG J, LUO Q, DUAN HC, PENG H, ZHANG Y, HU JP, LU Y. Efficient whole-cell catalysis for 5-aminovalerate production from L-lysine by using engineered Escherichia coli with ethanol pretreatment. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10: 990. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-57752-x

|

| [43] |

NIU PQ, DONG XX, WANG YC, LIU LM. Enzymatic production of α-ketoglutaric acid from l-glutamic acid via l-glutamate oxidase. Journal of Biotechnology, 2014, 179: 56-62. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.021

|

| [44] |

LIU QD, MA XQ, CHENG HJ, XU N, LIU J, MA YH. Co-expression of l-glutamate oxidase and catalase in Escherichia coli to produce α-ketoglutaric acid by whole-cell biocatalyst. Biotechnology Letters, 2017, 39(6): 913-919. DOI:10.1007/s10529-017-2314-5

|

| [45] |

CÁMARA E, LANDES N, ALBIOL J, GASSER B, MATTANOVICH D, FERRER P. Increased dosage of AOX1 promoter-regulated expression cassettes leads to transcription attenuation of the methanol metabolism in Pichia pastoris. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 44302. DOI:10.1038/srep44302

|

| [46] |

HAUPKA C, DELÉPINE B, IRLA M, HEUX S, WENDISCH VF. Flux enforcement for fermentative production of 5-aminovalerate and glutarate by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Catalysts, 2020, 10(9): 1065. DOI:10.3390/catal10091065

|